|

Daniel and Rachelle once again hosted an outstanding seminar weekend with Master Chen, bringing together Ottawa Chen-style Taiji practitioners and special guests from Toronto and New Hampshire. Over three enriching days, attendees had the invaluable opportunity to deepen their practice under the expert guidance and profound knowledge of Master Chen. |

Summary of the Three-Day Training

|

|

Seminar Benefits

Personal Notes and Observations

“Want to be good at Taiji? Be a dummy!”

|

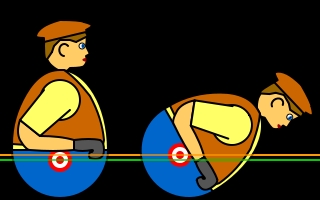

Master Chen illustrates the ideal structure for Push Hands and Taiji applications using the motion of a vanka-vstanka, a traditional Russian roly-poly toy. In this toy, the top remains light while the bottom is weighted, ensuring that no matter how forcefully one pushes, it never topples. This principle is mirrored in Push Hands practice, where maintaining softness in the upper body and stability in the lower body fosters resilience and balance. |

|

“Taiji practice can be likened to two panes … ”

… of glass separated by a vacuum. While each pane efficiently conducts heat, the empty space between them serves as a barrier to energy transfer. In Taiji, the goal is to expand this space, increasing resistance and refining control over energy exchange.

“The Taiji form should exhibit self-similarity, maintaining scale invariance across all movements.”

|

A fundamental principle in form practice is that distance becomes irrelevant once the aim is established. Mathematically, this concept aligns with self-similarity or scale invariance—meaning that, regardless of the length scale, the integrity of the form remains unchanged.

Imagine a snowflake—it has intricate patterns, but if you zoom in on a small piece, you’ll see that the same kinds of patterns repeat at different sizes. That’s an example of a self-similar structure. |

|

In Taiji, this means that the movements and principles of the form remain consistent regardless of whether they’re performed in a large, exaggerated manner or in a small, subtle way. The underlying mechanics, alignment, and energy transfer don’t change—they simply adapt to the scale.

Another simple example is a coastline. If you look at a map from far away, it has a jagged outline. If you zoom in, the details may change, but the jagged, irregular nature remains—it follows the same patterns no matter the level of zoom.

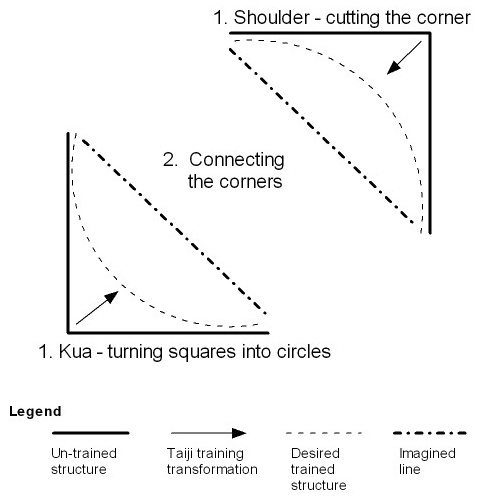

“Make the square a circle and chop off the corner!”

|

A core principle of Taiji form is the maintenance of a rounded kua and shoulder. When these structures become angled, they disrupt the seamless transfer of energy. Taiji training emphasizes pulling the kua forward—shaping a square into a circle—and relaxing the shoulder to dissolve rigidity, cultivating fluidity and harmony.

This concept is visually represented in the accompanying figure, where both the shoulders and kua form an open triangle, its corners linked by an imaginary line. Taiji practice involves maintaining the integrity of this imagined line while gradually bringing the apex of the triangle closer to it. Through consistent training, we refine the physical sides of the triangle, transforming its initial straight edges into the rounded quality of a circle—the ideal trained structure. Ultimately, this progression allows the apex point to align more closely with the triangle’s imagined hypotenuse, embodying the evolution toward a more harmonious Taiji form. |

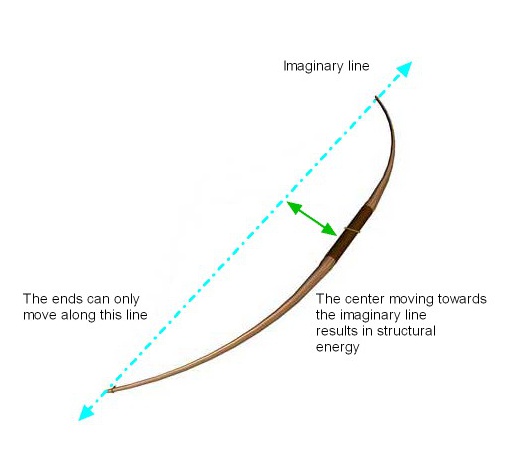

“Tied the ends”

|

Once you have established the curved structure in your kua or shoulder, the next step is to align that curve with an imaginary line connecting its endpoints—much like a bow. The tension between these endpoints generates structural power, known as peng energy.

The accompanying figure visually illustrates this concept. The bow represents the physical structure of the shoulder or kua, while the imagined line functions like a bowstring, virtually connecting the two ends and facilitating the storage and transfer of energy. Peng energy is rooted in the principle of Yin-Yang Separation, where the amount of energy depends on the distance between two points—one on the imagined line and the other on the physical structure. |

|

|

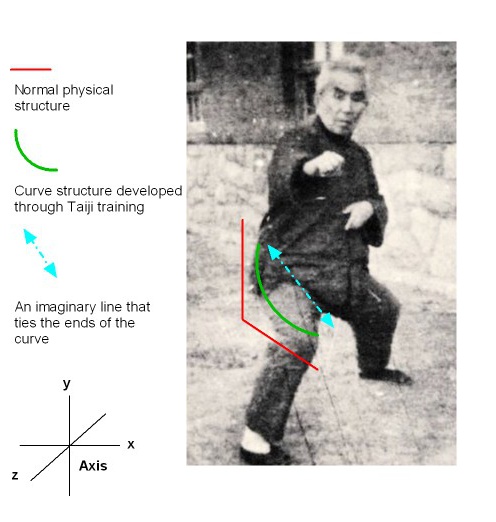

I have included a photo of Grandmaster Hong to illustrate the concept of transforming squares into circles. The picture was taken in his later years, yet he still maintains a low, wide stance with remarkable stability. Even in such a stance, the sharp angular structure of his ankle, knee, kua, and shoulder remains clearly visible. To embody the principle of squares becoming circles, his internal muscles and ligaments generate the tension that serves as the source of Taiji power. Understanding these principles allows us to appreciate Grandmaster Hong’s legacy even more. |

“Taiji is as easy as 1,2 3 Part 2.”

In the last seminar, Master Chen introduced the numbering of 1, 2, and 3 as a fundamental concept in Taoism—an idea that reappears in the practice of locking.

To cultivate structural energy, a student must understand the principle of locking body components in place, which involves stabilizing specific parts to optimize movement and power.

In Taiji, three types of locks are categorized by the numbers 3, 2, and 1, corresponding to ‘deadlock,’ ‘double lock,’ and ‘single lock.’ Each number represents the dimensions that must remain fixed:

|

|

Taiji training involves the strategic manipulation and arrangement of these locks across different parts of the body. Typically, the Taiji form is practiced with:

|

“How to learn real Taiji?

Grandmaster Hong often emphasizes this philosophy, offering the following reminder:

|

|

This principle extends beyond the precision of a single movement—it embodies the philosophy of training itself. Trust in the Practical Method, and progress will follow.

How do you know when you actually get it (achieve a certain level in Taiji)?

If you are persistent, and correctly apply the principle of Taiji, then all actions will use structural energy and involves Peng energy. As Grandmaster Hong said

|

|

The analogy is that of a professional carpenter who can hammer endlessly without tiring or being injured because he is using and manipulating energies in the correct manner.

|

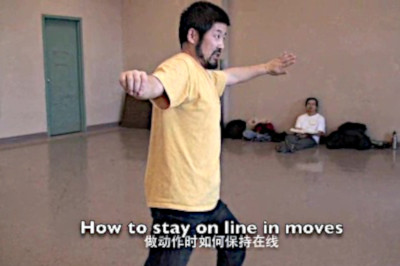

2011 March Ottawa Workshop Trailer

Highlights Key concepts of linework, including the principle of “No protrusion, no indentation”. Covers foundational techniques and principles related to body structure.

Duration: 35 minutes

Difficulty Level: 3/5

|

|

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

MING, thank you for a great summary. It is concise and clear. The figures were great for understanding. There were two parts, however, that I do not understand well. The different types of locks and the details about the goal AFTER cutting the curve. In the latter case, how do you (a) actually move and (b) which part of the imaginary line do you aim, with respect to the description “then you need to move the curve towards an imaginary line that connects the end of the curve”? Thanks.

I have added two new figures to try to explain the concept.

In the figure ” The three locks as seen on Grandmaster Hong”, you can see the representative dimensions that must be fixed and the corresponding dimensions where movement is possible. Remember, you need to apply this concept to many points on the body.

In the figure “Visualizing the concept in Grandmaster Hong”, the imaginary line represents a line of force. Like the analogy of the bow, the end of the bow moves in a line but as a result of the action, it brings the center towards this line. I will add another picture to help people visualize this.

Ming, thank you very much for taking the time to make those diagrams. As you say, it was a very good workshop. The university students all felt it was the ‘best one yet’; I think they are starting to understand Master Chen’s perspective and are beginning to be able to respond to what he is showing.

thanks for the notes…..and pictures! Nice.

Thank you very much for these great notes and diagrams. I really appreciate the effort you, and many others, put into sharing with other students what you’ve learnt from Master Chen.