|

Master Chen’s insights, illuminated through analogies like the bicycle and the door hinge, alongside the wisdom of his mentor Hong Junsheng and Taoist principles, underscore that genuine mastery in Taiji and beyond is a journey demanding dedicated time, disciplined focus, and a willingness to learn through consistent repetition and unbiased observation. This path requires taming the restless mind, adhering to fundamental principles without deviation, and cultivating a deep presence that allows for profound understanding to emerge organically, ultimately leading to a transformative personal experience that transcends superficial knowledge. |

| This lecture has been edited and enhanced for clarity first presented by Master Chen in Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. |

|

|

Introduction

Practiced globally by millions, Tai Chi Chuan stands as a preeminent Chinese martial art, celebrated for its health benefits and elegant movements. Its widespread appeal indicates a profound resonance across diverse cultures, rooted in both its tangible advantages and its rich history. In the West, however, this history is often perceived through a lens of Eastern mysticism.

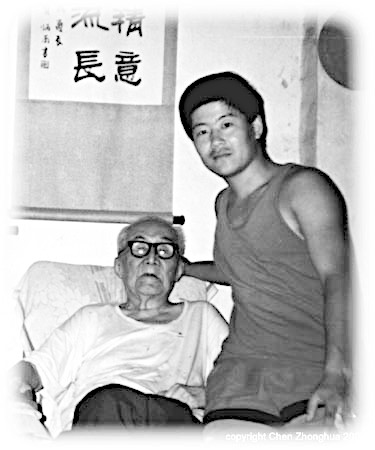

Masters Hong Junsheng and his teacher, Chen Fake, bridged traditional China and the modern era. Master Chen Fake’s life journeyed from the rural Chen Village to the vibrant heart of the Chinese empire, Beijing. Despite witnessing significant societal shifts, he remained unwavering in his Taiji teachings. Master Hong, born into a scholarly Confucian background, trained directly under Master Chen. Throughout his life, even amidst China’s turbulent political landscape, Master Hong dedicated himself to Taiji practice. In our own era of rapid technological and social change, Master Joseph Chen continues this lineage, adapting its preservation for a new world.

|

A scholar deeply versed in Confucianism, Master Hong embodied its principles and consistently attributed his Taiji mastery to Chen Fake. Despite the emergence of his teachings being referred to as the Hong style within martial arts circles, he never claimed to have founded a new branch of Chen style Taiji.

Understanding the power of nomenclature, Master Hong carefully defined his approach. As he was not a Chen family descendant, he intentionally avoided labeling his practice “Chen Family Taiji.” To distinguish his instruction, he chose a single, pragmatic descriptor: “Practical.” Eschewing grand or theoretical titles, he stressed the necessity of grounding theory in reality. While prioritizing Taiji for health, he resolutely maintained that its martial efficacy should never be neglected. |

Hong Junsheng |

Following Master Hong’s commitment to precise representation, Master Joseph Chen upholds the same principle of authentic transmission by utilizing workshops, hands-on demonstrations, and comprehensive video documentation to safeguard and share the true essence of Chen Tai Chi in the digital age. His tireless efforts in conducting workshops, offering practical guidance, and building a multimedia archive ensure the enduring presence of this profound art.

1. Tai Chi and the Art of Bicycle Maintenance

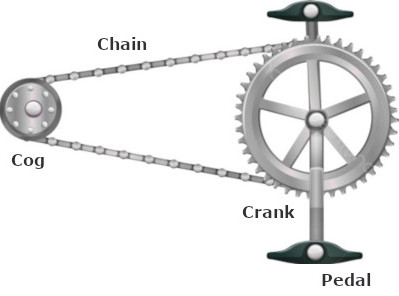

Taiji principles can be observed in everyday objects, including the mechanics of a bicycle. Let’s take a closer look at its power train.

|

In early bicycles, the drive train was a simple system consisting of two gears connected by a chain. The first gear, attached to the crank, is powered by pedaling, generating the force needed for motion. The second gear, known as the cog, is connected to the rear wheel, translating the force into forward movement. The chain serves as the critical link between the crank and the cog, transferring power efficiently between them.

However, in older or poorly manufactured bicycles, a loose chain often led to mechanical issues. When the chain lacked proper tension, slack would develop, particularly along its lower section. |

This slack could cause the chain to jump off its gears when the bicycle encountered a bump or sudden movement. As a result, riders frequently had to carry a screwdriver or a small crowbar to manually reposition the chain whenever it dislodged. This recurring issue could be frustrating, as the chain could pop off unexpectedly—whether during sharp turns, rapid acceleration, or at particularly inconvenient moments.

Attempts to fix this issue by shortening the chain and removing a link may create a new challenge—if the chain is tightened excessively, reinstalling it onto the gears becomes nearly impossible. In the past, the solution was simple: you ride the bike until the chain has too much slack, remove a link, reinstall it, and continue this process until it can no longer be reattached. At that point, you either replace the chain or the entire bike.

This situation mirrors the human body. Daily use results in continuous wear and tear. Like a bicycle chain, the body undergoes constant tightening and readjustment. Eventually, a point is reached where repairs are no longer possible, and life itself comes to an end. While this reality may seem harsh, it reflects the inevitable cycle of existence.

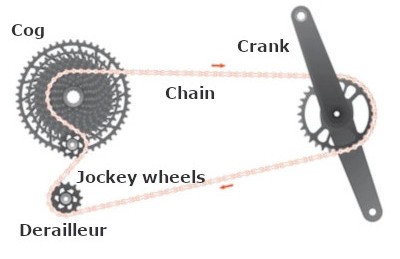

derailleur |

Modern bicycles offer a solution to this problem that aligns with Tai Chi theory. They incorporate an additional component in the drive train known as the derailleur—a small, triangular-shaped cage equipped with jockey wheels that guide the chain. The derailleur serves a straightforward yet crucial function: it adjusts the chain tension by effectively altering its length. Once the optimal tension is achieved, the chain is locked in place, ensuring smooth movement without the risk of derailment. This innovation allows the bicycle’s drive train to undergo a tangible transformation in size—something not observed in the human body, where all components remain a fixed size. |

You can learn from this bicycle analogy and apply it to your Practical Method training.

|

For a correct Taiji action, both theory and its physical requirements must be present. Take the Positive Circle as an example—specifically, the movements 1-In with Elbow and 2-Turn with Waist. Here, the front shoulder plays a crucial role.

Theoretically, the action of the shoulder is similar to the derailleur on a bicycle. Both the shoulder and the derailleur are triangular-shaped components that mediate tension. In a bicycle, the derailleur regulates the tension between the crank and the rear wheel, connected by the chain. Similarly, in Taiji, the shoulder manages the tension between the arm and the torso. When you first begin training, you may notice issues with your shoulder—such as the front shoulder popping up. This happens because, once the elbow is fully pulled into the body, there is no room for the second action (Turn with Waist) to occur. |

positive circle |

The progression within the Practical Method is designed to create physical changes in your body. Over time, as you train, your body will adapt, allowing more space for the ‘Turn with Waist’ movement. Without this transformation, every time your elbow tucks into your body, you will encounter a restriction that prevents you from executing the next move.

Now, you can see that everything Master Chen teaches is anchored in this principle—the theory demonstrated through these examples serves as the very foundation of your training.

2. The Path to Mastery: Patience, Discipline, and True Transformation

|

Master Chen emphasizes that true learning and mastery require time and dedication: “Whatever I teach, nothing can be done tomorrow—that’s why I cover a variety of training techniques and different approaches to practice, ensuring steady progress over time. With consistent effort, your body will adapt, allowing you to physically perform these exercises correctly.”

Do you see now? These are all important physiological factors. Master Chen is not teaching you something that can be instantly mastered—this isn’t about simply switching from one movement to another overnight. |

If you find yourself stuck, it’s not necessarily the fault of your action or choreography; rather, it’s a matter of physical restriction within a joint. You need to open the joint up. Stretch until the adhesion in this area are broken and released, allowing for proper clearance. This process takes time—though there is a minimum time required before progress can truly be seen.

If you’re lucky, your issue is comparable to treating a mild disease—some problems might resolve in as little as two weeks. However, if the issue is severe, it could take up to 10 years to fully improve. That’s why Master Chen’s role is to guide you, provide the right techniques, and assess whether you’re grasping the principles correctly. But ultimately, real progress comes from consistent training on your own. Without dedicated effort, fundamental change won’t happen, and you’ll revert to old habits—that’s the challenge.

To truly transform your body, strict adherence to the rules is the only solution. In practice, the biggest obstacle isn’t a lack of understanding—people often know what they need to do. The difficulty lies in the disconnect between the body and the mind; without unity, lasting improvement is impossible.

3. Taming the Monkey Mind: The Path to True Mastery

|

As human beings, most students struggle to overcome the monkey mind—the tendency to jump from one idea to another without deep commitment.

You follow Master Chen’s instructions for a week, but then you come across a video on YouTube where someone is doing something different. It looks impressive, and you decide to try it. That new approach feels easier, so you stick with it for a while. But soon, you realize there’s no real progress—no actual change in your practice. |

This cycle is universal—every human experiences it. That’s precisely why Tai Chi is worth discussing: true mastery demands focus, consistency, and patience to transcend this pattern. After all, all training is about shedding bad habits and cultivating new, purposeful behaviors.”

Consider this—you tend to act based on what feels right in the moment, whether at home, at work, or in relationships. But those same patterns persist. Take your relationships as an example.

That issue you had with your girlfriend? It doesn’t magically disappear when she becomes your wife. Later, when she’s the mother of your children, the same dynamic plays out—maybe she’s frustrated because you forgot to wipe the table after eating.

She sighs, rolls her eyes, and says, “How many times do I have to tell you? Just wipe the table!”

And fifty years later? You’re still having the same conversation.

|

But here’s the thing—we cling to these little struggles. In a strange way, we choose to suffer because we fear that if we simply learn to wipe the table, something will be lost. It’s almost as if we believe that without these small conflicts, there’s no connection—that if she stops reminding you, maybe she stops talking to you altogether. So, you keep forgetting. She keeps reminding. And the cycle continues—not because you can’t change, but because deep down, you’re afraid that if you do, something between you will disappear. |

|

In everything, the pattern is always the same—especially in learning.

The real challenge is deviation. You start on a path, but sooner or later, you stray from it. And if you don’t deviate? Something transformative happens.

Master Chen often uses the analogy of polishing a sword to illustrate this problem.

Every sword begins as a crude piece of metal. If you simply follow the system—polishing it consistently, sometimes for 30 years—you eventually create the sharpest sword imaginable. It’s a simple, straightforward process.

Yet, based on Master Chen’s experience, within any group of people, some will inevitably deviate. They’ll find excuses—taking a bathroom break, grabbing a coffee, getting distracted. The list of reasons is endless.

As Master Chen puts it: “[In the end, except for the student who gets distracted.] Everybody’s got a sharp knife. You don’t have one. Something substantial, something real, must happen. Because… it does not happen in your head. It does not happen with all your excuses. Something has to truly happen. Our problem is that we start doing something different from what everyone else has been doing.”

The lesson? True mastery comes from unwavering commitment—not from distractions, shortcuts, or excuses.

4. The Evolution of Tai Chi: Learning, Adapting, and the Risk of Distortion

|

One of the major component of Practical Method training is the practice of forms – a series of choreographic movement designed according to Taiji principles. Master Chen explained, “One thing we discuss in the Practical Method that Hong promotes is called ‘the form.’ We do not question it. We do not worry about who created it. We do not concern ourselves with whether it is right or wrong.” To illustrate this idea, he added, “My way of expressing this is to tell people, ‘My Practical Method was actually created by aliens. Don’t rely on human reasoning to analyze it.’ I’m simply saying—it’s a form. So, what does it do?” |

Master Chen continues,”By conforming to the form and subjecting your body to its rules, transformation occurs—over time, your body changes.”

Master Chen points out the biggest dangers in form practice. He said “Our natural instinct is to learn a form and gradually pinpoint the movements our body struggles to perform. Rather than allowing the form to shape us, we adjust it—modifying the difficult parts until they fit within our limitations. In the end, we don’t truly embody the form; instead, we use our so-called ‘intelligence’ to reshape it for everyone.” This alteration is another example of the monkey-mind. Well intention and understandable but causes irreplable demage. The result of this deviations are as Master Chen pointed out “You started with Chen style, but in the end, it became your own. Right? Then you learned Chen style again, yet this time, it turned into Yang style. So you went to Yang Luchan and studied Yang style—until, in the end, you called it Wu style. Then you pursued Wu style, but ultimately, it became Guangping style. And after Guangping style, you called it Li style. Why?”

Mater Chen declared that “The unspoken truth [that my Master] Hong refers to is that the form is simply either right or wrong. That’s just how it is.” Violating this principle results in the following “After 20 or 30 years, when you finally begin teaching, the original master might say, ‘But that’s not how I taught it.'” As a result, you may begin by learning the Yang style, only to find yourself practicing as a Wu stylist in the end.

As an American, clarity of thought is often a defining trait—especially in places like New York, where people tend to see the world in clear distinctions of right and wrong. For them, something is either correct or incorrect, with little room for ambiguity. However, many others approach life differently, embracing the nuances between good and bad.

This idea surfaces profoundly in Tai Chi training. You may study diligently under a master, yet your form evolves into something slightly different from your teacher’s. How do you reconcile this discrepancy? One perspective is that your form remains correct, but has been personalized through your individual understanding. It’s akin to an artist who sets out to paint a bowl of apples but ends up with a still life resembling a melon. Instead of recognizing the deviation, he justifies it by saying, “Well, anyway, the melon is better than the gourd.”

As Master Chen insightfully points out:“They are all illustrations of human thinking. We’re always capable of doing that. So every person who learns something will end up changing it. And you always have an excuse for that change.”

|

The evolution of Tai Chi is rooted in this very tendency—every style traces back to Chen style, yet how these variations emerged remains a mystery. This way of thinking, where individual interpretation shapes practice, has long influenced the art.

Master Chen illustrates this with a story: “When Hong was teaching me, he told me about his class of around 20 students, with Chen Fake standing at the front as their teacher. One day, Chen Fake turned around, looked at the group, and asked, ‘What form are you guys doing? I thought you came to learn from me—what style is that?’ He saw that each student was performing their own version of the form. Over time, this led most of the group to leave, until only seven remained. But even among those final seven, each person’s form looked different.” |

|

The common explanation—the one you hear all the time and have probably considered yourself—is that we’re all different. We look different, our body sizes vary, and we come from different backgrounds. So how could two people possibly perform the same form in exactly the same way?

It’s an appealing idea: I’m different, he’s from China, I’m from America. He’s short, I’m tall. He’s small, I’m big—so naturally, our forms must be different

But then, as you lie in bed at night, just before sleep takes over, you begin to wonder…

Why is it different? Because you didn’t copy it correctly. But when you do copy it correctly, the differences—whether in nationality, appearance, or background—shouldn’t be visible. Because, in the end…

As Master Chen highlights: “When the idea—the essence, the theme, the underlying truth—is correct, people should be able to see it.” As a result, the details don’t matter. From a distance, a knowledgeable observer can instantly recognize a performance—whether it’s the Chen Village practitioners, the Beijing group, or the students of Master Hong’s Practical Method.

Master Chen continues: “It means that, good or bad, you inevitably have certain characteristics. So why not refine them further—shaping and adding more—until the differences become unrecognizable? You might even hear someone say, ‘You look just like your teacher.’”

The truth is, achieving that level of exactness may seem impossible—and that’s perfectly fine. Perhaps true replication is fundamentally unattainable. As Master Chen observes, ‘The problem is that you decide to justify it,’ using the perceived impossibility as an excuse to abandon the task.

A transcendent ideal requires no justification, whereas perceived impossibilities lead to deviations—or even the abandonment—of a task.

Master Chen offers the following illustrations from Taoism: “It is impossible for us to separate Yin and Yang. If you consider Yin as Earth and Yang as heaven, then everyone must go to heaven upon death. There is no need to ask for details—such as which religion one must follow to reach heaven. The essential requirement is belief in God. There is no need to specify God’s name or appearance; rather, one must simply hold faith in a higher authority that created everything. In the end, we will return to that source. If that belief is true, then it is true. Otherwise, you can’t make up excuses.”

Master Chen then apply this example to Tai Chi training. “We understand that the form embodies an ultimate aspiration. In my lifetime, I know I cannot execute it perfectly—but I will not give up. And I refuse to justify my mistakes by claiming that I am right and my teachers are wrong. … Each day, I’m going to be a little bit better than today.”

Master Chen goes on to explain how easily one can stray from the proper path. After training for a while, you keep noticing a flaw in your form. Frustrated, you tell yourself, ‘Tomorrow, I’m going to give up.’ You justify it by thinking, ‘Forget about the one who taught me. In the end, I’ll quit him—he wasn’t that good to begin with.’ Now, you’ve found an excuse. Even as you continue training with your own modifications, you seek validation: ‘I get someone to write me a few lines, telling me this change is much better.’

Master Chen concludes, ‘Don’t justify your inability to reach the ideal state. We live with problems, with mistakes—they become part of us. Even when others call you a teacher or a grandmaster, you still recognize your own flaws. And that is the only way progress happens.’

5. Lessons in Humility and Growth from Tai Chi

Master Chen emphasizes the wisdom of his mentor, Hong Junsheng, saying, ‘Hong lived for 90 years. He published his book shortly before his passing—a work originally written in his youth but refined over 17 years of revisions.’

Master Chen recounts an event in the publishing history of this book.

Master Chen was present when a publisher attended Master Hong’s morning class, urging him to publish his book. To provide context, the publishing landscape in China has changed significantly. Today, money can make publishing accessible, but in the past, it was a rare achievement—only about 20 books were approved each year.

The publisher had authority but lacked the knowledge to write a Taiji book. He was an editor at a publishing house that approved such works, yet he had never written one and didn’t know how. Determined to publish Hong’s book, he approached him with a proposal.

|

Hong asked. “Do you know Taiji?”

“No, but I’m an editor,” the man replied. Hong continued. “Then how are we going to publish it?” The editor confidently said, ‘Well, I have the authority. We’ll publish the book together. You write it, I’ll put my name first, yours after mine, and we’ll publish it together.'” Hong says, “Well, are you really going to take responsibility for this book when you don’t know Taiji? ” The editor shrugged. “but you know Taiji.” |

|

|

Hong pressed, “When it’s published, what are you going to do?

The man said matter-of-factly,” I’m going to edit your book. I’m an editor.” Hong asked, “How are you going to edit it? The stuff I write, do you understand it? The editor reply bluntly, “I don’t have to understand it. I’m an editor.” So in the end, Hong refused. Master Chen asked Master Hong, “Why did you refuse?” |

Practical Method Volume One |

As the conversation unfolded, it gradually shifted toward the core issues. We moved beyond the discussion of publishing, authority, and all the troubling aspects surrounding it.

Master Hong reflects, “I’m not going to publish a book because every day—sometimes even every other day—I wake up and realize that my understanding has deepened. What I thought yesterday now needs revision, because today, I grasp it a little better than before.”

He continued by explaining, “That’s why, in ancient times, a person could publish only one book.” When he finally published his book before his death, he acknowledged that it contained many mistakes. Accepting this fact, he stated, “I am responsible, but I don’t feel bad anymore because this is how long I’m going to live. I don’t have any more time to contribute to it. When I was young, I wrote it. But as I grow older and look back at this book, how can I truly see it the same way? What happens in my mind? At my current level, I believe that everything in it was wrong.”

Master Hong described the problem of publishing a flawed book: “Many people in the world cling to that flawed book as if it were a Bible. It’s not fake—but it is full of flaws. Am I supposed to spend another 20 years urging people not to follow its instructions? Because now, I see how shallow my understanding was back then.”

He addressed this challenge with a deeply responsible approach—choosing to publish his book only when he could no longer revise it. He concluded, “I have no regrets about the things I can no longer do. But for now, I can still change. Yet we’re not talking about change in the broad sense—not about altering everything, not about changing principles. We’re talking about the same concept.”

6. Master Hong’s Method: The Power of Repetition and Discovery

|

Master Chen use this example: “Rotation—you know, 10 years ago, I didn’t truly understand it. And yet, I’ve been teaching and speaking about rotation for 35 years. Every day, I come to realize just how profoundly deep it is. We always convince ourselves that we know how to rotate—but in reality, we don’t.”

Master Chen explains, “Hong’s method teaches that for anything important, there will always be something you don’t fully understand. However, there are aspects of it that you do grasp. That’s why it’s crucial to repeat what you understand. Keep repeating it until, one day, you suddenly realize—oh, there’s something I missed! Or perhaps, something I simply hadn’t considered.” |

Master Hong’s approach is deeply rooted in his Confucian scholarship, embodying the wisdom found in The Analects (论语). One of its fundamental teachings states:

“知之为知之,不知为不知,是知也” —”To know what you know and to acknowledge what you do not, that is true wisdom.”

This principle underscores the value of intellectual humility and continuous self-refinement. In any meaningful pursuit, there will always be elements beyond immediate comprehension. Yet, by focusing on what is already understood and reinforcing it through disciplined practice, deeper realizations naturally emerge over time. Master Hong emphasizes that genuine growth does not come from seeking mastery prematurely but rather from patiently uncovering new layers of understanding through persistent engagement.

Master Hong’s method has universal applications, but how does the movement of a door hinge relate to the rotation in a Taiji action?

Master Chen explains “In Taoism, we believe everything is the same as everything else. Meaning this simple thing here,” pointing to a door hinge “is, in essence, the same in deep theory as the most sophisticated computer.” This idea can be found in Zhuangzi (庄子) which states ” 天地与我并生,而万物与我为一。” (Tiāndì yǔ wǒ bìng shēng, ér wànwù yǔ wǒ wéi yī.) Which translates to: “Heaven and Earth were born together with me, and all things and I are one.” Even seemingly unrelated objects can uncover fundamental universal truths—principles that can then be applied across different contexts.

7. From a Simple Hinge to Profound Taiji Wisdom

Master Chen uses Master Hong’s technique to deepen his understanding of rotation. He describes his process as follows: “Every day, that’s why you hear the door creak. I know it might seem foolish, but still—every night before I sleep, I hold the door, staring at the hinge. Then, I go through the same process, retracing every thought. I open the door. The door moves, but the hinge remains still. What happened? I ask myself again and again. What happened? I notice the casing (the knuckle), the rod (pin). When this occurs, why does the hinge not move? Where did the force go? It must have gone either up or down. Right now, I can’t think of anything else. And so, I repeat this routine—every single day.”

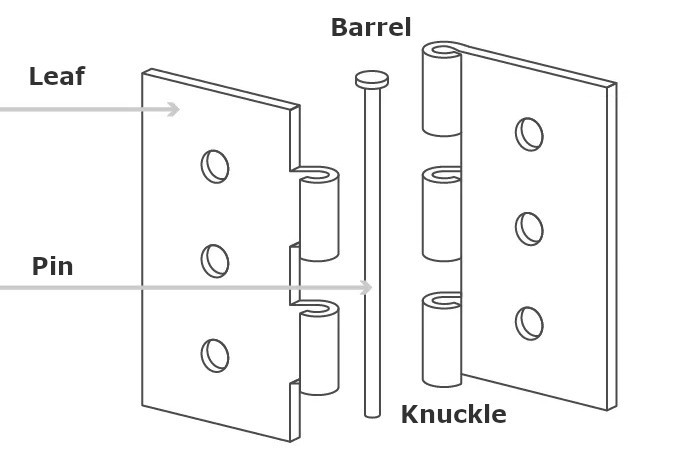

Let’s follow this same process. First, visualize a door hinge and establish a clear understanding of its components. What is a door hinge? What are its main parts?

|

A door hinge allows the door to pivot smoothly while remaining securely attached to the frame. Its primary components include two leaves—flat plates that fasten the hinge to the door and frame using screws through designated screw holes.

The barrel, which forms the rotating section, consists of the knuckle and pin. The knuckle is the cylindrical part created when the leaves interlock, serving as the hinge’s pivot point. |

The pin runs through the knuckle, securing the hinge and enabling rotation. As the door opens or closes, the leaves swing around this pin.

Additionally, the hinge plays a crucial role in supporting the door’s weight and distributing it to the frame, ensuring stability.

Master Chen carefully observed the system, studying the movement of the door as it swung open and closed. He examined the leaves and barrel, noting how the knuckle and pin responded to each motion.

What caused the creaking sound? What defined a well-functioning hinge? When did a hinge fail to do its job?

With quiet persistence, he repeated his observations, seeking a deeper understanding of the mechanics behind each movement—gradually unraveling the mystery of rotation itself. But how did Master Chen ultimately reach enlightenment? To be enlightened is simply to see beyond what was once familiar—to perceive something new.

Master Chen elaborates “After years of studying hinges, I stumbled upon an old door at my high school—one with a history etched into its frame. Originally built in 1927, it had already endured decades of daily use. When I first encountered it, the door had been swinging open and shut for 15 years straight, a testament to its enduring mechanics.”

Master Chen then points to the knuckle and pin of a hinge. He describe the clearance between the top of the pin and the knuckle. Commenting that if a door is not used for a long time, there will be rust on the hinge. He also noticed that there is more clearance between the top of the pin and the knuckle if the door was being commonly used.

Master Chen continued “For 15 years, I sat in the same classroom, always surrounded by the same doors and hinges—familiar fixtures in my daily routine. One day, I watched as the maintenance worker entered, carrying a small hammer. He moved from door to door, opening each one, then gently tapping the pin back into the knuckle.

It was a ritual performed once a month—a simple yet effective fix, far more economical than replacing the hinges entirely. Those hinges were built to last—solid, well-crafted, enduring.”

Master Chen explains this ritual “In the original design, when the door is fully open, there is no gap between the pin and the knuckle—the pin fits snugly into place. However, over time, as the door repeatedly swings open and shut, the pin gradually shifts out of the knuckle. Eventually, it may pop free from the casing and fall to the floor.

This is why doors typically have multiple hinges—to prevent failure if one loses its pin. The maintenance worker’s job is to routinely inspect the spacing between the pin and knuckle for each door hinge. If the clearance becomes too large, a simple fix is to hammer the pin back into place.

With a school as large as mine—home to around 2,800 students—this task is no small feat. Checking every door takes an entire month, and by the time the last door is inspected, it’s already time to start the process again.”

Master Chen described his realization: “When horizontal motion is restricted and the door swings open, the energy must be redirected. In this case, it transfers into the barrel of the hinge. Every time the door opens and closes, a significant amount of energy is generated, much of which becomes trapped within the hinge barrel. But energy can’t simply disappear—it has to go somewhere. So where does it go? Instead of dispersing horizontally, it moves vertically. Over time, this vertical force causes the pin to gradually shift upward, slowly working its way out of the knuckle.”

Master Chen relates this concept to Taiji practice: “So this is what Taiji has been talking about. That’s exactly what my teacher, Master Hong, was saying.”

He demonstrates the idea through the action of “in with elbow”: “Whenever you move horizontally”—for example, pulling your elbow into the body—”and you eliminate this move here”—the backward movement of the body—”when you turn like this here”—continuing with the next motion of “turn with waist”—if the central axis of the body remains stationary, then “the energy has to split this way,” moving vertically along the central axis.

Master Chen emphasizes, “And so this is called converting horizontally into vertical” within the Taiji system.

The two movements, “In with elbow” and “Turn with waist,” are not merely superficial gestures but carry profound significance. True Taiji training focuses on fully encasing the torso to eliminate horizontal movement, much like the knuckle of a hinge encasing the pin—where the pin remains stable, free from lateral motion.

In natural circumstances, when the body receives energy, its instinctive reaction is to disperse it through movement. However, Taiji training seeks to restrict and ultimately eliminate horizontal responses, allowing incoming energy to manifest purely as vertical movement.

|

Master Chen demonstrates this principle, revealing that any residual horizontal movement results in a visible tossing effect within the body. By bracing the torso and preventing lateral motion, incoming forces that would typically turn the body sideways instead transform into an upward and downward extension.

He explains: “This head is stretched out. It becomes very long. Then, you lock the top of the head at Bai-hui (GV-20), the acupuncture point at the crown. In response, the central axis must stretch downward. If you lock the bottom of the central axis at Mingmen (GV-4), the lower spinal acupuncture point, then the central axis must stretch upward. By locking both the top and bottom, the internal structure becomes highly compressed.” |

|

He continues: “This feeling of compression—before recognizing the barrel of the hinge—I was just going through the motion.” Demonstrates the action with exaggerated tossing or backward movement of the rear shoulder. “It wasn’t necessarily wrong, but it wasn’t fully right either. The movement lacked depth, making the overall available energy quite shallow. But once you begin locking the torso and aligning with the vertical axis, the energy has no choice but to be released outward.”

He concludes “It took me 15 years to grasp this one simple concept: eliminating horizontal movements. I only understood it because I kept doing it wrong—repeating the same action without seeing any change. There was just one more thing I couldn’t figure out. But when you start comparing, when you truly look, you realize you’ve been staring at the same thing all along. ”

8. Seeing Without Looking: The Taoist Path to True Perception

Master Chen highlights how the study of Taiji rotation through the simple mechanism of a door hinge reflects a broader, universal approach to understanding the world. He illustrates this concept by referencing the discovery of gravity.

He begins: “For millions of years, trees have shed their leaves and fruits, like apples, each fall. People—collectively as humans—have watched this happen for generations. And yet, despite witnessing it countless times, no one truly questioned the underlying cause.

Humans have been around for an unknown length of time—perhaps 27,000 years, just as a rough estimate. During all those years, people observed the same phenomenon, maybe even pondered it, but nothing significant came of it. Then, one day, Newton saw an apple fall and had a realization: **it fell because of gravity**.

Why did that moment click for him when it hadn’t for others? It was the result of constant observation—watching again and again, with no breakthrough, until suddenly, everything made sense. One day, something happens.”

Master Chen concludes: “This is called to observe with the intent. That intent is not the same as you happen to be there. Do you understand?”

He explains: “I could have spent 15 years in that classroom without ever truly seeing—without ever recognizing the significance of the hinge. Or, I could have been looking. But looking alone isn’t enough.

If I try to see something—if I force understanding—it won’t happen. You can’t grasp it simply because you want to.

Instead, you must follow the process. This is crucial. Master Hong’s method emphasizes repetition and careful examination of what you already understand. Keep repeating, keep analyzing.

Commit to it fully, and over time, something will emerge—clarity will come.”

Master Chen warns: “If you approach it with intent, nothing will happen.”

In other words, if you follow Master Hong’s process while holding preconceived notions, your ability to experience genuine change or enlightenment diminishes. True understanding comes not from seeking a specific answer but from fully engaging in the process—allowing discovery to unfold naturally over time.

You are encouraged to follow the wisdom of the Chinese proverb “察微知著”—which translates to “Observe the subtle to understand the obvious.” This principle emphasizes the importance of keen observation, where careful attention to small details leads to a deeper comprehension of broader patterns and effects.

Master Chen uses this example to illustrate the problem with intent. He explains:

“If you step into this room searching for a straight sword, your focus narrows. You scan the space, fixated on finding it. But in doing so, you miss everything else—the objects, the details, even the people around you.”

You won’t notice that someone is wearing a black fleece sweater. You won’t remember who else walked into the room—because to you, they’re just humans, indistinct, unimportant to your search. Your mind is locked onto one thing: the straight sword.

This is the nature of intent. When you hold a rigid expectation, everything else fades into the background. Even if a sword sits right before you, slightly curved instead of perfectly straight, you won’t see it. Because all you’re searching for is the straight sword. Not finding it here, you move on to another room, still chasing the same singular vision.”

Master Chen concludes: “In Taoism, this principle is expressed as: when there is no intent, it is the true intent. You cannot approach with a fixed expectation, yet you must still be present. If you are absent, whatever unfolds here will remain unknown to you.

True intent arises only when intent is absent. To embody this, you must come without preconceived notions—open, receptive, and impartial.

Yet there is another essential element: presence. You must be fully present in all things. Physically, you must be here. Mentally, your mind must be clear—free from distraction, free from intent.

To be truly present means to be awake, unburdened, and open. No lingering thoughts, no worries, no resistance. Simply here—aware, yet without expectation. And in that state, understanding will naturally reveal itself to you.”

As Lao Tzu succinctly states, ‘无为而无不为’ – ‘By not forcing action, nothing is left undone.’ This expresses the Taoist principle of wu wei (无为; effortless action), where true effectiveness arises not from imposing one’s will but from harmonizing with the natural flow of things.

Master Chen elaborated on the importance of presence, saying:

“In Taoism, we believe that if you have clear vision—free from cataracts or other impairments—and an optometrist certifies your eyesight as perfect, then when you open your eyes, nothing in front of you escapes your perception.

It’s like a camera capturing an image. When you take a photo, every detail in the frame is recorded. If ten people stand before you, the photo will show all ten; it’s impossible for one to simply disappear.

Now, do you see? Your brain functions in the same way. When truly clear, it perceives everything—without omission, without distortion.”

Lao Tzu, in the Tao Te Ching, writes: ‘至虛极,守静笃’ , which translates as: ‘To the mind that is still, the whole universe surrenders.’ This expresses the Taoist belief that deep stillness—cultivated through presence and an untroubled mind—leads to profound clarity and harmony with the universe.

Master Chen continues: “When your mind is fixated on something, your perception narrows—you see only that one thing. As human beings, we all share this tendency. It’s not about right or wrong; it’s simply how focus works. For example, young men often find themselves drawn to a beautiful woman in a room—so much so that they may fail to notice anyone else around them. That’s the truth of attention.

You can deny it, you can say, ‘I’m not like that,’ but fundamentally, the mind operates this way. This is intent. When something captures your focus, it dominates your awareness—you keep looking at it, and everything else fades into the background. But the reality is, those other things still exist; they are simply overlooked.”

Master Chen describes methods to overcome the problem of narrowed focus. He explains:

“Because you are here, your eyes are open, and information continues to enter. But when your mind is focused on one thing, everything else is stored away, never surfacing. There are ways to retrieve that information, but in learning, the most important approach is to be present.

To be present means to pay attention. Paying attention is not about actively searching for something—it is about maintaining clarity. Use your eyes properly; if your vision is poor, wear glasses. If tears blur your sight, wipe them away. But do not force yourself to ‘see’ something, because the moment you do, your vision becomes restricted.

The same principle applies to listening. To truly hear, your ears must be open and receptive. If you constantly strain to catch distant noises—wondering, ‘What’s that sound outside?’—you will miss what is being said in front of you.

All of these ideas remain theoretical until a moment in life reveals them in full. Only then does true understanding take root.”

Master Chen shares a story that perfectly illustrates both the power and the pitfalls—of focus.

|

During one of my trips to China, I made a habit of recording all my demonstrations and sharing the video with my students for further study. At a large gathering in Jinan, I filmed a form demonstration and later passed the video along.

Then came the questions. One student kept asking me about something he saw in the video. The problem? No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t understand what he was talking about. |

|

It wasn’t until much later that I realized what had happened. As I was performing my form, there was a young man in the background warming up for his competition routine—his movements were unusual, distinct.

My student had watched my video, but instead of focusing on me, his attention was completely locked onto that guy. The result? He never actually saw my performance.

Now, imagine this: day after day, this student stared at the video, obsessing over the competitor in the background. “What is that form? What is that form?” He was convinced it was part of the footage I had given him.

So, naturally, I reviewed the tape. I watched, rewound, looked again—but nothing. Whatever he thought he saw, it wasn’t there. Still, he insisted the form was in the video.

Determined to solve the mystery, I checked every other demonstration recorded on the tape, then expanded my search to all the videos I had made around that time. And after all that effort? Nothing

But here’s the twist—I wasn’t even thinking about a random guy in the background. I assumed the student was talking about another form that had been performed later in the video. My mind was caught in a loop: one video, another video, another video. Yet the answer was sitting right there, unnoticed.

That tape had about ten demonstrations on it, and despite all my searching, I never found the form he was referring to. Years later, I happen to watch the same tape with that student. He asked me about the form again.

I looked at the screen perplexed. “But that’s my form.”

He replied. “No, no—look there. See that guy?”

I stared. Then it hit me—three years of watching, reviewing, questioning, and debating… and I had never seen that guy. And he? He had never seen my form.”

For Master Chen, the story offers this lesson. Focus can reveal, but it can also blind. You don’t always see what’s right in front of you—you only see what your mind is already looking for.

Master Chen concludes “I realized that everything the Taoists speak of is real. Without direct physical experience, two people discussing the same concept may seem to be in agreement—but in reality, they are not truly speaking about the same thing. This is why, in the Practical Method system, personal experience is essential to understanding.”

9. The Art of Learning: Presence, Focus, and the Path to Mastery

|

Master Chen reflects:”I’ll admit—I have a habit of being a little blunt. That’s actually one of the reasons I don’t bring my wife to my workshops. She always tells me, ‘You can’t talk to people like that!’ And I just blink and ask, ‘Like what?’

I try to be more mindful now. Whenever I catch myself being rude, I remember her words. But at the end of the day, I’m not striving to be a great teacher—I just want to be a good person. That’s why I ask my students, ‘Did you hear me?’ And they nod and say, ‘Yes, I did.’ ‘Okay, then repeat what I said.’ And most of the time? They can’t. So, did they really hear me? |

Understanding is even trickier. I ask, ‘Do you understand?’ They confidently say, ‘Yeah, I understand.’

‘Great! Then tell me what I said.’

See, when someone claims they understand, I want them to paraphrase my words—to explain the concept back to me in a way that aligns with what I actually meant. This is how I can tell if they truly grasp it. And you’d be surprised how often this method reveals the gaps in comprehension.

For example, let’s say I’m explaining the mechanics of a hinge—the way horizontal energy converts into vertical movement. Then I ask a student to repeat it, and they immediately say, ‘I think it’s made of copper.’

Technically, that’s a valid observation. It is made of copper. But that’s completely beside the point.

I spent all this time talking about energy transfer, and they responded with material composition. Now, if I tell them they’re wrong, they might push back—’But Master Chen, I can prove it! I can scrape the surface and show you it’s copper!’

They’re not wrong. But because their knowledge led them down a different path, they missed the lesson entirely.

This is why intent matters. When your mind is already focused on one thing, it leads you away from everything else—even when the answer is right in front of you. It might sound bizarre, but trust me, it’s very, very real.”

Master Chen emphasizes the importance of one simple yet powerful practice: taking notes. ‘When you are practicing, you need to actually do one thing—make notes. Real learning comes from making notes.’

Keeping a physical record serves as an objective way to track your progress, allowing you to see patterns, refine techniques, and deepen your understanding. More than that, Master Chen recommends it as a method of gaining insight into your own mind—turning observation into awareness and practice into mastery.

Master Chen outlines a structured system for categorizing different learning paths within his practice: “In my school, I categorize students into different groups based on their level of involvement.

Some people simply watch my videos and try things on their own. They don’t know me or my students, and that’s fine—they form the larger audience. I also create content for people who aren’t interested in my system but might pick up one or two useful insights from my videos and writings.

Then, there’s another group—those who are committed to learning the form. They aren’t formally connected to anyone but study on their own and pay closer attention to details. Over time, these individuals may move into a specific category on my website: Practical Method Students—people actively learning the system.

Beyond that, I have workshop students, all clearly categorized. If you register for a workshop, you’re added to the system, where you can see everyone who has trained in my workshops. But here’s the real challenge: progress.”

|

Master Chen explains his approach to tracking progress: “Let’s say today, through training, you reach level 65. Tomorrow, when you return, you start at 38 again. You train, you warm up, and eventually, you get back to 65. The day after? Still 65.

So, the big question is—how do you reach 100? In reality, learning works through repetition. Tomorrow, you start at 38, do two circles, and reach 65. Someone without training might take all day to get there. This is the shortcut—repetition builds familiarity, and your body remembers the process. |

|

But what is 65? It means you’ve warmed up, and your body is ready to move. Without consistent practice, it could take all day just to feel that moment of readiness—and then suddenly, the day is over. But through steady training, knowledge accumulates. One day you start at 65, then a month later, you reach 75.

In Chen Taiji, consistent training can push you toward 99% very quickly—toward what I call 99 degrees. But to reach 100, you need someone to point out the final adjustment. That one correction, at the right time, makes everything click.

This is the path. Every day, you reset to 38 or 36. You train all day and only reach 65. And without taking that final step, you’ll never reach 99 and beyond.

There is no shortcut. Progress is like water heating to a boil—at 100 degrees, it turns to vapor. Before that, it doesn’t matter how hot the water is, because what we want is the transformation—the vapor.

This idea applies to the body as well. And while some might connect it to qi, I’m not saying you have to train for qi itself. But just like vapor, qi is an air-like form—not something physical.”

The lesson? Commit to the process, keep training, and one day, that final step will take you beyond limits you didn’t even realize existed.”

| In this thirty-minute lecture, Master Chen shared profound insights, weaving together analogies like the bicycle and the door hinge with the wisdom of his mentor, Hong Junsheng, and the guiding principles of Taoism. His teachings emphasize that true mastery—both in Taiji and beyond—is not achieved overnight but unfolds through dedicated time, disciplined focus, and a commitment to learning through consistent repetition and unbiased observation. This journey demands the taming of a restless mind, unwavering adherence to fundamental principles, and the cultivation of a deep, present awareness. |

|

Through this approach, understanding emerges naturally, ultimately leading to a transformative personal experience that transcends mere technical knowledge.

Cogito, ergo sum

|

René Descartes originally articulated this idea in Latin as “Cogito, ergo sum.” He first published it in French as “Je pense, donc je suis” (“I think, therefore I am”) in his 1637 work, Discourse on the Method. This work is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in Western thought and a foundational step toward the Enlightenment.

However, from a Taoist perspective, this conclusion is not only flawed but potentially harmful. Cartesian philosophy prioritizes the act of thinking and the individual self, directly contradicting the Taoist principle of Yin-Yang, which emphasizes balance and interconnectedness. |

By failing to recognize a complementary counterpart to the self, Cartesian thought promotes a fragmented view of existence—one that isolates rather than harmonizes.

It is remarkable how just three small words have shaped the intellectual DNA of the West, deeply influencing its approach to knowledge and learning. Yet, this emphasis on rational thought can become an obstacle to Taiji progression, fostering excessive intellectualization at the expense of embodied experience and intuitive understanding of the physical world.

For the Taoist, the response is simple: ‘Tu moreris. Tamen iter pergit.’ (‘You die, yet the road continues.’) In seeking to transcend Cartesian limitations, Zhuangzi offers a profound key: “‘因任其所遇,顺而不失其正,则无忧矣’—’By entrusting yourself to what comes, moving in accord without losing your true nature, you will be without worry.'” This insight encourages a deep acceptance of life’s unfolding, interwoven with an unwavering commitment to one’s principles.

This perspective offers a significant departure from the Western philosophical tradition’s prioritization of rationality, proposing instead a way of being deeply connected to the inherent flux of existence—where a mindful yielding to life’s continuous unfolding reveals a more profound understanding.

While Descartes anchored reality in the cogito, “I think, therefore I am,” Zhuangzi suggests that true harmony resides not in the fixity of intellect but in the suppleness of adaptability—a state where thought and experience become indistinguishable aspects of the spontaneous unfolding of being.