|

Based on a Workshop conducted in Ottawa in 2014, this text conveys the exploration of Chen Style Taijiquan through Grandmaster Hong Junsheng’s Practical Method. It covers the demanding training philosophy emphasizing rigorous practice over theory, and outlines the art’s history from Chen Village and its lineage through significant masters like Chen Fake. The content also examines the art’s connection to Taoist philosophy, the balance between health and martial application, and the core training principles and verifiable testing fundamental to this method, providing a comprehensive overview of its key facets. |

Introduction

|

Master Chen has dedicated his life to sharing the profound principles and benefits of the Practical Method. His generosity knows no bounds—each year, he offers free lectures to the public, inviting them into the intricate world of Taijiquan. Few masters take the extra step of preserving their wisdom in video form, but Master Chen is one of those rare individuals who ensures his teachings endure.

Watching his videos is an experience in itself. His deep expertise and sharp, engaging style captivate audiences, offering both seasoned practitioners and curious newcomers valuable insights. But the true magic lies in re-watching them. Each lecture unfolds like layers of a masterful lesson, revealing nuances and perspectives that deepen one’s understanding over time. |

Spanning decades, these countless hours of recordings demonstrate a remarkable consistency—his message remains precise, his insights ever fresh. The following edited transcript is from a two-hour lecture delivered at an Open House in Ottawa in 2014, more than a decade ago. For the general audience, it offers a glimpse into how Master Chen distills complexity into clarity. And for those already well-versed in the subject, it serves as a cherished moment where the Master speaks directly to you, sharing the wisdom of a lifetime devoted to exploration. The original video from the event can be found in the Ottawa Open House 2014 (for members only). You can find my thoughts on the open house is in this Ottawa Open House Workshop Review. There is also a full Q&A video here, and an edited transcript of this Q&A section entitled “Time is life“.

|

1. The Practical Method: Learning Through Action, Not Overthinking

I’ve been coming to Ottawa to conduct private workshops on the Practical Method for over 15 years. This is the second open house here, but the first truly great one. I host open houses all the time—so many, in fact, that I’m starting to think I should earn frequent flyer miles for them. Just last weekend, I was in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and next week? Who knows, maybe back to China. Honestly, I can’t keep track of them anymore!

In any case, welcome to the open house for the Chen Style Practical Method. Before we begin, I suddenly realized something about this place: we have to hurry up and get started! We’re trying to provide you with as much information as possible in a short two hours. Originally, I thought it was just going to be a quick 15-minute introduction.

Since we are in Ottawa, I now understand that everything must be in Chinese, English, and French. Eventually, we should also include Spanish. Later on, we should add coffee and pastries. We can keep it going all day — this is no joke. That’s just how things are in Canada.

I fly all the time, and only on Canadian airlines. Even though I often travel long distances, I never seem to have time for anything. I usually like to work on the plane, as I need to listen to recordings from my workshops, but I am constantly interrupted. Whenever there is turbulence, the flight attendants inform me about the situation in four or five different languages: English, French, Chinese, Japanese, and some other Southeast Asian language. The interruptions are nonstop, and sometimes it gets difficult because I need some peace and quiet.

| What I’m trying to say is that, when it comes to learning the Practical Method and practicing Tai Chi, the time allocation should be such that no more than 5% of your time is spent thinking, reading, and analyzing. The rest of the time should be dedicated to practice. In modern society and our everyday lives, we have moved away from this approach. We have lost control of everything — we only think about things instead of actively doing them. According to the Practical Method, everything is merely a product of our imagination. |

|

According to Taoism, we live in an imagined world and no longer dwell in reality. This is something the Chinese discovered around 4,000 years ago. We had already transitioned into a society based on imagination back then. In the last 50 years, with further advancements in technology, we have fully entered this type of society. As a result, we have lost our sense of direction and our connection to physical reality.

2. Chen Style Taijiquan: The Origins and Legacy of a Timeless Art

Taiji is an expression of Taoism. The Practical Method is a system that originated from Taiji. Speculations about how and why Taijiquan was created — let’s leave those as myths. We know that Taiji has an incredibly long history. Some believe its origins date back more than 1,000 years, while others place it clearly at least 400 years ago. The exact details of its creation are less significant now, as it occurred so long ago and lacks direct physical evidence. What matters most is that Taiji continues to be practiced in China and across the world. Additionally, there are many different styles of Taiji.

Of the styles, we recognize that Chen Style Taijiquan (陳氏太极拳) was one of the earliest. From Chen Style, we have four other family styles, named after the founders of each: Yang (楊), Wu (吳), Wu-Hao (武-郝), and most recently, Sun (孙). Today, there are hundreds upon hundreds of styles of Taijiquan in China. However, in my view, these new styles do not count because only history can decide. Perhaps after another 50 or 100 years, if a style endures, we will know it is legitimate.

Today, in China, virtually every teacher labels their Taiji as their own style. Only the five family styles have stood the test of time. All five family styles acknowledge that the first historically identified Taijiquan is Chen Style.

|

What came before Chen Style? We don’t really care at this stage; otherwise, it’s pure speculation. The problem of origins is the same as asking about the origins of a person. My last name is Chen, but how did I get this name? I can trace it back to my father, but how did my father get his name? Such reclusive questions will eventually spiral into speculation and myth. For me personally, I know that, historically, at least for the last three generations, we have been Chen. This represents a clear history.

Historical documents point to the fact that Chen Style came from a person called Chen Wangting (陈王廷; late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty, approximately from 1600 to 1680). He was the 9th-generation member of the Chen family from Chen Village (Chenjiagou, 陈家沟), located in Wen County (温县), which is part of Jiaozuo City (焦作市) in Henan Province (河南省). It was recorded that he performed and practiced a form of martial art. At that time, there was no name for it. Later on, they called it Chen Style Taijiquan. He passed on the art within Chen Village. |

|

There was a large gap in that history until Chen Changxing (陳長興; 1771–1853), the 14th-generation master. He taught a man called Yang Luchan (楊露禪; 1799–1872). There are many stories about Yang Luchan. The basic history is that Yang Luchan came from another place, went to Chen Village, and studied martial arts. Some people say he wasn’t allowed to use the name of the art, wasn’t allowed to practice it, or wasn’t allowed to stay in the village. Anyhow, he learned martial arts from the Chen family and from Grandmaster Chen Changxing. He then left and eventually ended up in Beijing, where he started teaching. The legacy of Yang Luchan is what we now call Yang Style Taijiquan.

The history of Taijiquan is very clear from that point onward. Yang Luchan was highly skilled in martial arts. In some recollections, he was already very accomplished before going to Chen Village to study. He was so talented that he later earned the name “The Invincible.” |

|

It’s similar to how, today, someone might be called a champion or something of that nature. This simply means that nobody could defeat him. Due to this reputation, he was hired to teach the royal family in Beijing. That is a concise summary of how Taiji gained its name and its popularity. Eventually, we arrived at what we have today—different varieties, different styles, and various reasons for practicing Taiji.

3. Taijiquan and Health: A Direct Path to Well-Being

There are some very simple reasons to take an interest in Taijiquan. One reason is health. Another is martial arts. But no matter what we say, the real reason must be health. And then we also fancy that by practicing Taiji, we can learn and develop some martial abilities. What does that really mean? Do we truly need it as a martial art in the present day? Do we need martial arts at all? Ultimately, all martial arts are sports. They are spectator sports, designed to make you feel good about yourself. When it comes down to it, the only real benefit we can gain from practicing Taiji is health.

I want to continue on this track, following the Chen-style Taiji Practice Method in this aspect of health. So, what is health? In general, for many people today—I cannot say with certainty about the West—but in China, many people simply compare ages when discussing health. For example, if my master lived to be 53 years old and your master lived to be 107, then your master must be healthier. According to the Practical Method, such conclusions are erroneous—they are not rightful comparisons.

In the Practical Method, health means health. Health does not mean longevity. Longevity is simply longevity. As you can see, the Practical Method is straightforward—simple in the sense that it is direct.

Today, we cannot do that anymore. Whatever you say, people think, “Oh, do you mean we should do this so that we can achieve that?” The general audience cannot accept this direct approach and always seeks an interpretation for “better understanding.” The simple and direct approach is: “It just means do this so that we can do that.”

It is very important for the Practical Method to preserve this idea as part of the tradition.

4. Navigating Perspectives: The Chinese Way vs. The Western Way

|

I’ve been talking back and forth without offering a clear map. This is the Chinese way. The Chinese way is like a star map— like stars in the sky.

A star map doesn’t offer a single defined path—it’s a collection of points scattered across the sky, connected in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. You navigate by intuition, finding patterns as you move rather than following a predetermined route. Only when you step back do you start to see how everything fits together. This is how people traveled in China in the past. |

The Western way is a linear map that guides you from point A to point B, carefully explaining all the steps needed to get there. In the West, there are streets and highways. The best highways are designed with no exits.

Once, I was driving from New York to Washington, D.C., with a Chinese group. Somewhere along the way, we missed an exit. We had to drive about 45 minutes farther before finding another exit and making our way back. As you can see, on a highway, missing an exit can cost you a lot of time. But that’s the way it’s designed — otherwise, you could never go very fast.

In contrast, the Chinese way allows you to move in all directions, which might not be fast. In the end, the audience must piece everything together. Putting such a puzzle together is fairly difficult since you don’t start with a clear picture or road map. In any case, we wander all over the place so you can enjoy the view.

5. Taiji, Tao, and the Struggle Against Nature’s Order

The structure of Chen-style Taijiquan is very simple. In the Practical Method, the requirements are even simpler. The rules are clear: the outside is outside, the inside is inside, left is left, right is right, top is top, bottom is bottom, front is front, and back is back. But when you really think about it, satisfying those rules is the most difficult thing to do. The simplest actions are often the hardest to achieve — the universe just works that way. However, it is possible. Let us consider this example.

| The universe is like a balloon. If you add more air, the balloon expands. If there is less air, it shrinks. At no point do the parts of the balloon change position. What does “parts changing position” mean? Have you ever seen a balloon — now this is crazy when I say this — with air outside and the rubber inside? That’s not even a possibility. If such a thing existed, would you even call it a balloon? Right?Therefore, the fundamental concept of a balloon is that “outside is outside, and the air is inside.” If the air is outside, there is no balloon, is there? So, in Taiji, we say everything must follow this order. Unfortunately, although this simple example may seem clear to you at first, the moment you stand up and attempt to practice Taiji, you quickly realize that adhering to such rules is entirely impossible in practice. |

|

Just look at me standing here. As soon as I move, the top of my head starts to go downward. That’s not right according to the Taiji rules. We just said, ‘top is top.’ When a position moves, we call this tendency to move its intention. So, when we move, and the head starts to go down, in Taiji terminology, we say that ‘the head is intending to go down,’ which is wrong according to Taiji principles. The head must intend to stay on top.

We can apply this analysis to other parts of the body. Look at the elbow—it is inside. Look at the hand—it is outside. According to Taiji rules, the elbow must stay inside, and the hand must stay outside. When someone punches towards me, I immediately reach out with my hand to block it. Can you see that the Taiji rules have been broken? My hand reaches towards my body, so now the hand intends to go inside. The arm bends, and the elbow is now outside, meaning the elbow now intends to go outside during the block. But we always do this, violating the Taiji rules. Can you see all the mistakes? When no body part obeys the rules, you will get chaos. Our body is just built like that. If you follow the Taiji rules, you cannot move.

Let us write the Taiji rules on the wall, stand there, and gaze at that wall. Then you realize that if you follow those rules, you cannot move. Perhaps that’s why people began practicing standing meditation—so they wouldn’t have to move. You can experiment with many different approaches, but when you revisit the instructions, you see that every move you make is wrong. After many failures, you finally come to understand that we can do anything except follow nature.

The universe was made like that, described by those Taoist rule. We are a product of the universe so we should follow those rules. Yet, we somehow, and this is a speculation, according to the Practical Method, somehow along the way, we became sentient, we started to think, we decided that we’re smarter and then we decided to do things on our own. When we did that, we are fighting against the universe, fighting against everything. Because of that, there is one definite outcome, that is death.

The universe says you must follow its way, or it will not allow you to exist in this place. As a result, we live in a cycle of life and death. Every living thing you see follows this pattern. Every time a life form becomes smarter, its lifespan becomes shorter. A rock, which lacks even the intelligence of a tree, lasts longer than the tree. The tree, which does not have the intelligence of a worm, will typically outlast the worm. You realize that every time something becomes very smart, it dies earlier. The universe has its own form of intelligence, and we are aberrations from that. Chen Style Taijiquan’s Practical Method is based on the ancient system of Tao (道), a concept from Taoism.

Following the Tao means moving in harmony with the original rhythm — what we call the original breath of the universe. When we find this rhythm, we instantly become one with the universe. That is what we call the Tao. In Taiji, when you find the Tao, we say you’ve got “it.” In other words, we say that one becomes immortal.

So far, this concept parallels with the Chinese thinking on communism. It’s a beautiful idea, but an idealistic one. In reality, it does not happen, because we have already stepped out of the Tao. Do you see? We were once part of the Tao, but we left — we became independent of it. To return, there is only one path, but it is not an advisable one.

6. Lao Tzu, Taoism, and the Unexpected Wisdom of Taiji

|

The creator of Taoism is called a man called Lao Tzu (老子). He did something very, very important. Later generations fabricated a story about him, completely inventing the idea of Taoism. His enlightenment came when he realized that humans are the sole source of the world’s problems. Everything else lives in harmony with the earth. He leapt onto a green cow—some say a blue one—or an ox, riding it backward as he disappeared into the forest. Most people either forgot or misunderstood his message. He believed that only by surrendering himself—riding a cow into the forest and allowing the tiger to consume him—could the earth truly survive. As long as humankind exists, destruction follows. Wherever man goes, he builds cities, erects monuments, and cuts down trees. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, he dismantles everything in his path. Lao Tzu came to the painful realization that he himself was part of the problem. His solution was to return to nature. |

He ended up as food for the tigers in the forest — but that’s not something most Chinese people want to believe. People made up a story, saying he just walked into the forest. Since no one actually saw him die, they figured he must still be out there, immortal. It’s just human nature—wanting to believe someone can live forever. But the truth? He had simply reached enlightenment. His enlightenment was the realization that he himself was the problem. I’m definitely not saying you should sacrifice yourself for the planet—I’m just here to encourage you to do some Taiji instead.

What is Taiji? It means being less destructive to yourself and less destructive to the things around you.

|

When it comes to Taiji fighting, the method is simple—you defeat your opponent using only two things: a hug or a kiss. Depending on how you feel that day, you can hug him to death or kiss him to death.

Hugging him to death means taking away his space. You become one with him, so he can’t fight you anymore. If he doesn’t like that, he can choose to be defeated. If he does like it, then you both win. |

|

Kissing him to death covers two possibilities. In one, your opponent enjoys the kiss, so there’s no fighting. In the other, he absolutely hates it, so he runs away. Sounds like I’m joking, right? Well, ‘fighting is like kissing’ is actually written in the Taiji classics.

| Unfortunately, people today think that must be some kind of secret code. But nope—there’s no secret code. It’s simple. If you forget to brush your teeth in the morning, when you go in for the kiss, your opponent will run away. That’s just how it works, right?

That’s why I tell people I only brush my teeth at night—because during the day, I might run into bad people, and I have to fight them. And with coffee breath? That alone can take down just about anyone. Nobody can stand upright within a one-meter radius of me. |

|

So, this is Chen Style Taijiquan Practical Method.

7. Chen Style Taijiquan: Lineage, Legacy, and the Practical Method

According to authentic documented history, Chen Style originated from the lineage of Chen Village. Chen Changxing was the great-grandfather of today’s standard-bearer for Chen-style Taijiquan, Chen Xiaowang (陳小旺; born 1945), who resides in Australia and continues this lineage. I’m also part of the lineage, though not by name — meaning I am not from that family. My last name happens to be Chen, but I learned Chen-style Taijiquan from a master, through another master, within this lineage of martial art—not through a direct family connection to the Chen family. So, while I share the last name Chen, I am not part of the family.

According to the original lineage chart, I am the 19th generation practitioner of Chen-style Taijiquan. In recent years, however, China decided to change everything. As part of this, the authorities redefined the creator of what we recognize as Chen-style Taijiquan as the ninth-generation practitioner. Consequently, this ninth generation was designated as the first-generation practitioner of Chen-style Taijiquan, which makes me an 11th-generation practitioner.

Personally, I like numbers — just like money — the bigger, the better. Eleven feels smaller than nineteen, and I thought nineteen sounded better since it’s almost twenty. It’s like being older than a teenager, but eleven feels too small. However, when talking about lineage, eleven means you are closer to the original creator, which makes you “older.” But I don’t want to be older; I prefer to be younger. Right? I don’t want to walk around introducing myself as a fourth-generation, 300-year-old Taijiquan practitioner—that doesn’t sound good. Anyway, you’ll hear the terms 19th generation or 11th generation being used interchangeably, but they essentially refer to the same thing.

|

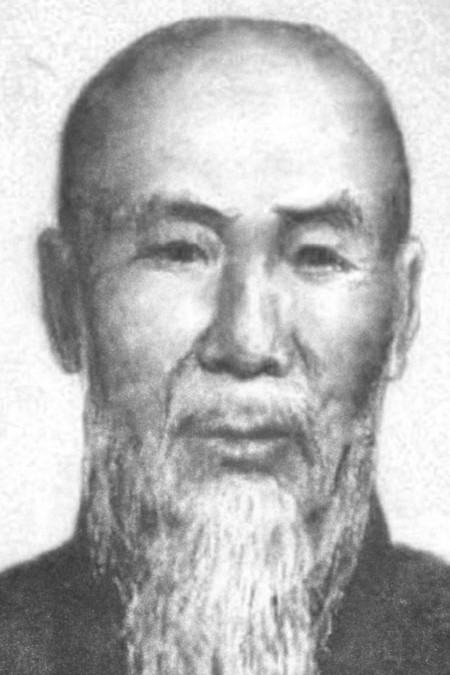

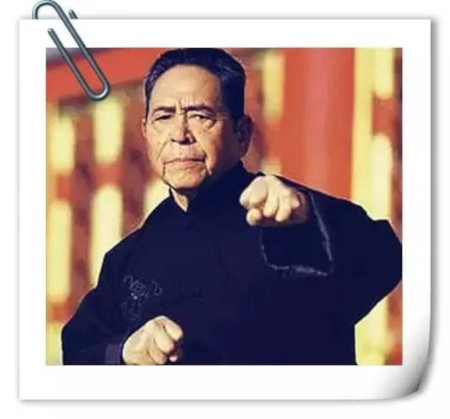

My master, Hong Junsheng (洪均生; 1907–1996), learned Chen-style Taiji from a man named Chen Fake (陳發科; 1887–1957). Chen Fake was the great-grandson of Chen Changxing, while Chen Xiaowang is the great-great-great-grandson of Chen Changxing. Chen Fake was the first person to leave Chen Village and teach Taiji elsewhere, which he did in Beijing in 1928. This marks the beginning of Chen-style Taiji’s relatively short history outside Chen Village. In 1928, Chen-style Taiji emerged from the village and became part of the global martial arts scene. Due to this short history, many people still do not consider Chen-style Taiji to be authentic Taiji, as it is very direct, very simple, and resembles martial arts. Before 1928, most people thought of Taiji as something soft and unrelated to fighting. |

Chen Fake left a lasting legacy in Beijing, teaching many students during his lifetime. My first master, Hong Junsheng, was part of the first group of students Chen instructed. Later, towards the end of his life, Chen also taught Feng Zhiqiang (冯志强; 1928–2012), who became his last disciple—and my second master. Feng passed away just a couple of years ago, and the lineage I represent is deeply rooted in both Hong Junsheng and Feng Zhiqiang.

| Both of my masters dedicated themselves to Chen-style Taijiquan but approached it in very different ways. Hong developed what he called the ‘Practical Method,’ emphasizing how the training extended far beyond physical movements. For him, Taijiquan was about life itself—it fostered health, built friendships, and taught people to defend themselves without actual fighting. In his eyes, it was a tool for everyday living, and that’s why he described it as ‘practical.’ That philosophy defined his method. |

|

|

Feng, on the other hand, had a very different story. He was already known as an incredibly strong and skilled fighter before he even began studying Chen-style Taijiquan. But as he grew older, his views on fighting took a dramatic turn. He’d say things like, ‘What is fighting? It’s not good. Fighting is about causing harm to others.’ Over time, he became completely disillusioned with it. It’s easy to see why he felt that way—it made sense for him. The ironic twist is that this fierce fighter eventually focused solely on health and well-being. He created his own system, Hùnyuán Tàijíquán (混元太极拳), with ‘Hunyuan’ representing the integration of energy, matter, and consciousness. |

Hong also had a fascinating journey. He came from a scholarly family and attended Beijing University, but poor health forced him to leave. Seeking to improve his health, he turned to Chen Fake to learn Taiji, which Chen taught exclusively as a martial art. Hong became a highly respected and well-known fighter by the time he was 65. Yet, despite his success, he always maintained, ‘No, no, no—no fighting. The fact that you lost had nothing to do with me; it had to do with you doing something wrong.’ His denial that Taijiquan was about fighting, even as he excelled in it, remained one of the more intriguing contradictions of his life.

My approach to teaching Chen-style Taijiquan is deeply influenced by both Hong’s Practical Method and Feng’s Hunyuan System. Together, they form the foundation for how I represent and share the rich history of Taiji.

7. Chen Style Taijiquan: Precision, Testing, and the Pursuit of Mastery

Chen Style Taijiquan training focuses on the practice of forms—a series of choreographed moves. Yilu (the first form) is typically performed at a normal speed of 7.5 minutes. For young people, we usually keep it to around four to five minutes. If the performance is too slow, it can become dull for younger audiences and unsuitable for demonstrations. In practice, much like Yang Style, the slower the performance, the greater the benefits

During the seven minutes of performing all 81 moves, the body should remain stable, held at a consistent height. Movements cannot rise and fall except during transitional actions, where slight shifts in height are permissible. In each movement, the body must stay level and even. Additionally, the speed of the movements must remain consistent. Any variation in speed should only occur during transitions—when finishing one section and moving into the next. We aim to maintain the same level of power, weight, and structure throughout. With all these requirements, achieving perfect balance, proportion, and alignment becomes incredibly challenging. When these requirements are met, the form appears smooth and soft visually. However, in reality, the movements are not inherently smooth or soft; instead, they are executed with absolute consistency in size, height, tempo, and speed, which creates the appearance of smoothness.

| Another key aspect of the Practical Method is its emphasis on physical testing. By calling it practical, we mean that everything must be rigorously tested and proven. My student from Ottawa, John Dahms, was one of the first to conduct an experiment grounded in practicality, rigorous testing, and scientific principles. In the martial arts world, particularly in Taiji, people often talk about countless hours of practice or performing the form an extraordinary number of times. Some claim to have done 100 forms a day to achieve a certain level of proficiency. |

|

To me, it seemed like they were claiming to practice 28 hours a day, which didn’t sound very scientific. So I asked John, when he was much younger, to perform 100 forms a day while I supervised to ensure there was no cheating. We proved that the claims are plausible: starting around 4:30 in the morning and finishing at 9:00 at night, it is possible to do 100 forms in a day. However, to claim to have done this consistently for 20 years is unrealistic. It doesn’t account for having a job or managing other responsibilities of life. Such an activity is not sustainable. You can do it once, just to prove a point. It’s like young people today going to a party, exhausting themselves, and doing whatever they want for one night—but you can’t live like that every day.

In the Practical Method system, we use this idea as a benchmark for training. For serious students who have been consistently practicing six to ten hours a day, we suggest taking on this challenge. At my school on the mountain, we provide full support for students to test their limits and see how many forms they can perform in one session. Another Ottawa student, Brennan, told me his record was 150 forms in a single day—without cutting any corners.

|

In our school, we have a saying: ‘People only talk about performing 100 forms a day.’ However, we don’t push anyone to practice 100 forms daily—it’s not an ideal approach. For younger learners, this benchmark is more of a personal challenge to test their limits. Hitting that milestone helps them put things into perspective. It shows them that even training with 20 to 30 forms a day, as previous generations did, was already an incredible achievement. |

The Practical Method teaches students to avoid boasting or fabricating stories during training. It emphasizes staying grounded in reality. This can be difficult in the martial arts world, where exaggeration is common and a scientific approach is often lacking.

À la recherche du temps perdu

|

|

A decade ago, I attended the Ottawa Open House and eagerly chronicled my experience, convinced that my Taiji journey was unfolding with purpose. Fast forward ten years, and well—let’s just say that my commitment to Master Chen’s advice has been somewhat… theoretical. My mind twirls in Taiji’s imaginary realm, but my body? It slouches rebelliously, hunched over the keyboard, defying all proper posture.

Occasionally, I recall the Taiji rules — yet my outside insists on barging in, my inside keeps slipping out, and my stance remains a perpetual slouch. As for Taiji hugs and kisses? I’ve all but abandoned deciphering that mystery. Let the new generation sort it out.

Once upon a time, I assumed wisdom naturally came with age. Reality, however, delivered a humbling revelation: age merely refines the fine art of looking knowledgeable. Still, still—once in a while—when I revisit Master Chen’s old lectures and sift through my own neglected notes, a flicker of clarity emerges. Could it be? A glimmer of understanding, a step closer to cracking the elusive Taiji puzzle.

The philosopher Xunzi (荀子; 310–235 BCE) writes:

|

|

Theoretically, I agree. Practically? Some days, I’d much rather take a nap.