|

The journey into Taijiquan is often likened to navigating a profound, unfamiliar universe. Instead of a fixed, linear road, Master Chen provides a conceptual “Star Map,” where all the fundamental principles are laid out simultaneously. This powerful metaphor highlights the interconnected and non-prescriptive nature of the art, encouraging students to explore the constellation of concepts and forge their own integrated understanding. |

| This essay is the third installment in our series examining the full system of the Eight Methods (Bā Fǎ 八法). While our previous two essays detailed the theory and application of its core components—the Primary Energies (正勁 Zhèng Jìn) and the Four Diagonal Energies (隅勁 Yú Jìn)—this piece shifts focus to a crucial pedagogical strategy: Master Chen’s use of mechanical analogies. This is the central theme of our analysis. By following the teaching strategy of Master Hong’s Practical Method, we will examine curated video examples that leverage concrete physical comparisons to translate the entire abstract power and precision of the Eight Methods into immediately accessible and understandable terms. | |

| (This article is based on videos from the Practical Method YouTube channel.) |

|

Master Chen uses mechanical analogies to answer the question: “What is the Eight Methods of Taiiquan?”

|

|

Introduction

Part 1. Four Primary Energies (正劲)

Part 2. Four Diagonal Energies (隅劲)

Part 3. Mechanical Models

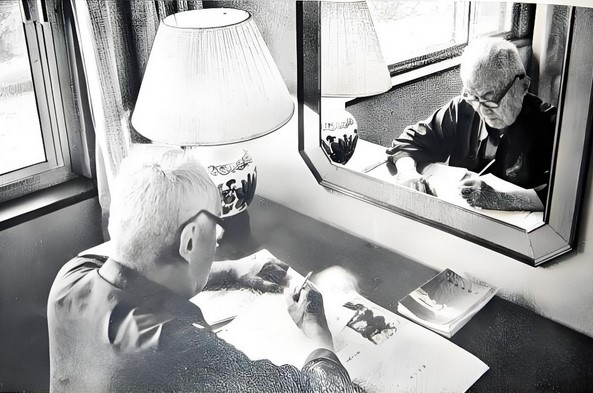

Master Hong Junsheng (洪均生) stands as a seminal figure in 20th-century Taijiquan, celebrated for his profoundly analytical and pragmatic approach to the art. His landmark work, Chen Style Taijiquan Practical Method (《陈式太极拳实用拳法》), represents a radical departure from conventional, often esoteric, descriptions by systematically applying the principles of classical Chinese mechanics to the discipline. Master Hong demystified the abstract concepts of the Eight Jin Methods (八法 Bā fǎ), also known as the Eight Gates (Peng, Lu, Ji, An, Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kao), by explaining their function through verifiable models: the lever (杠杆 Gànggǎ), the wheel (轮 Lún), spinning disc (转盘 Zhuànpán), the arc (弧线 Hú xiàn) and gears (齿轮 Chǐlún).

A direct student of Chen Fake (陈发科), the standard-bearer of Chen Family Taijiquan, Master Hong spent decades seeking to uncover the “how” and “why” behind the techniques. He concluded that the traditional Eight Methods are not merely static postures but precise mechanical functions—specific martial applications—powered by the rotation of the torso (the “wheel”) and strategically employed leverage. Master Hong’s approach is unique and essential to modern understanding because it:

|

|

This essay will explore how Master Hong’s use of these mechanical models provides an invaluable, tangible framework for understanding the true martial function of the Eight Methods. This foundational legacy—which prioritizes objective, physically grounded analysis over subjective experience—is a living tradition, a testament to the tireless efforts of his student, Master Chen Zhonghua, who continues to practice and disseminate the Practical Method of Chen Style Taijiquan today.

1. Lever (杠杆)

Based on the video Introduction to Practical Method Taijiquan. Nov 29, 2014.

|

Master Chen began by holding a long stick with both hands as shown in Figure 01A, introducing a mechanical analogy to explain the concept of Yin-Yang separation. He stated, “The stick is in one piece. There is one act that humans have discovered with a rod that is really transformative.”

Master Chen then adjusted his grip, moving one hand to hold the stick at its center point. He explained, “When you put something like this here—a pivot point somewhere between the end of the stick.” |

|

He proceeded to tilt the stick, balancing it on the pivot, as Shown in Figure 01B. Describing this movement, he declared: “Once you do that—use a pivot to create a lever system—now, there is Yin and Yang.”

Master Chen then emphasized the principle’s difficulty: “This Yin and Yang principle is very important, but it’s very, very difficult to do on the body.” Master Chen further explained the lever system from the perspective of the principle of Yin-Yang separation. He began by demonstrating the action, tilting the stick on a pivot point. |

|

|

“When you do this here, tilt on a pivot point,” he started, pointing to the center of the stick. “You can see this point at the middle of the stick. You can say that this point is a pivoting point—a point that does not move. You can also say it’s a demarcation line. Starting from here [on the right side of the demarcation line] everything on this side goes downward. In contrast, everything on that other side [on the left side of the demarcation line] goes upward.” This differentiation is seen in Figure 01C. |

Master Chen emphasized the uniqueness of this phenomenon by explaining, “If you close your eyes and I tell you that I have a stick with a special property that allows one side of the stick to move in one direction while the other side of the stick moves in the opposite direction at the same time—if you have never seen this idea of a lever with your eyes, based on this initial description, you would think there are two sticks. This is because one stick cannot move in two different directions at the same time without rotating. However, once you have a pivoting point, one stick can move in two directions.”

Relating the analogy back to Taiji practice, Master Chen concluded, “So this idea of a Yin-Yang separation is very, very crucial. All we want to do in Taiji is to create this action [of a lever] on our body. The analogy and the idea are very simple to understand. Every single person on earth hearing this explanation can accept this concept, but very few can actually carry out this action.”

Drawing a Positive Circle

|

Master Chen explained that the Practical Method system offers a specific training technique to achieve the Yin-Yang separation concept within the body. One component of this system is called “Drawing a Circle.”

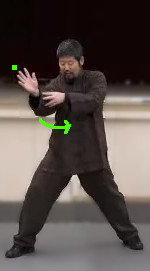

Master Chen began the demonstration in a ready stance to execute the Positive Circle exercise with his right hand (Figure 02A). He explained that this training is divided into three distinct sections, each defined by a phrase and a fixed point, or “anchor.” In the ready position, the first anchor is the tip of his right index finger, as shown by the green dot in Figure 02A. The initial movement then begins with the right elbow towards the chest (indicated by the green arrow). |

|

Section 1: “In with Elbow”

Master Chen summarized the initial movement with the phrase, “In with Elbow.” He then detailed the physical mechanics, explaining, “The whole body pulls back without the finger.” The finger acts as the segment’s anchor, remaining stationary (shown by the green dot in Figure 02B). Following this pull, the next movement is a turn of the waist, which is illustrated by the green arrow in Figure 02B. |

|

|

Section 2: “Turn with Waist”

The second segment begins with the command “Turn with Waist“. Master Chen demonstrated this by rotating his torso while maintaining two crucial anchors: the dantian, which stays completely immobile as the primary fixed point (green dot in Figure 02C), and the location of the initial hand position (the first anchor), which must be held as a visual focus or target. Once the rotation is complete, the sequence moves to the final action of this section: the extension of the right hand back to its original position, indicated by the green arrow in Figure 02C. |

|

|

Section 3: “Out with Hand”

Concluding the exercise is the third section, summarized as “Out with Hand“. Master Chen gave the defining instruction: “Without moving the Dantian, everything goes out.” He highlighted the importance of the final anchor, the rear foot, which remains grounded to power the entire outward action. It is essential that all three anchors from the preceding phases remain stationary (the finger, the dantian, and the rear foot), a stability illustrated by the three green dots in Figure 02D. With the successful completion of the outward movement, the right hand returns to its starting point, and the Positive Circle exercise can be seamlessly repeated. |

|

|

Master Chen provided a crucial principle regarding the Dantian’s role: “If you move the Dantian while you are carrying out your action, can you see this is just moving and does not have any purpose?” He used this question to warn against normal, ineffective movement where the Dantian shifts, as illustrated in Figure 04. In this example, the hand’s path (red arrow) appears circular, but the constant movement of the Dantian prevents the action from developing martial power. |

Master Chen then highlighted the foundational importance of the anchors in each section, collectively known as “The Three Nails of Taiji“:

- The first one: the front finger does not move.

- Second one: the Dantian does not move.

- Third one: the rear foot does not move.

He summarized the purpose of this layered training: “So when you do a circle based on three curvatures [segments of a circle], each one has a part that does not move. Taken together, that’s a full circle. It’s like one curvature, [‘In with Elbow’, fixes this part of the circle.] Two [‘Turn with Waist’, fixes this part of the circle] and then finally another [curvature, ‘Out with Hand’, creates the final segment of the circle.] So, adding all three segments together, that causes a complete circle. Therefore, there is no one real continuous circular action.”

The training method thus creates the illusion of a full, continuous circle by assembling three static-pivot movements, enforcing the principle of simultaneous movement and stillness (Yin-Yang).

Yin-Yang Separation in Practical Applications

Master Chen explained that the principle of Yin-Yang separation extends beyond solo practice and is essential for more complex situations, such as partner training and actual combat.

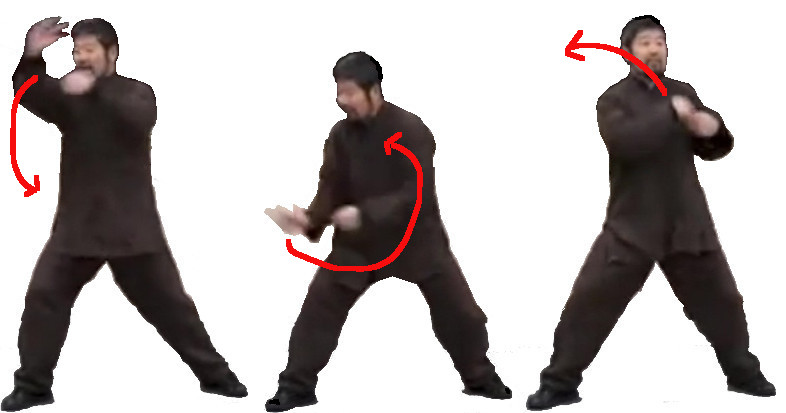

| He first described the common, yet ineffective, approach found in many martial arts: “When you do a drill with another person, we say, ‘Stay here, this is your move for attacking me.’ I go here to counter your attack.” Master Chen then demonstrated a series of choreographed follow-up moves: “I can lock you here, I turn and you fall down.” He used this example to illustrate the fixed, pre-arranged sequences typical of many training systems. Figure 04 is an example of a typical choreographed partner training. |

|

|

Master Chen pointed out the failure of this method in real combat: “Now, when we’re fighting, it [those clearly choreographed moves] doesn’t work anymore because you are moving, I’m moving. I try it [a specific technique] but you are moving. So it [the technique] doesn’t work.” Figure 05 shows an example of this move and counter-moves that typifies real combat. The green arrows shows the initial move and the red arrow shows the counter moves. |

The Practical Method system offers an alternative approach based on the Yin-Yang separation principle, which fundamentally requires a stationary (Yin) and a moving (Yang) component to succeed.

| Master Chen explained the strategic shift: “So now I don’t care how you move. I’m not moving. So you can attack me… and… because I don’t move, you [my opponent] have to be in a position that I can move you [with the technique].” By electing to be the anchor (the stationary Yin), Master Chen forces his opponent into a predictable relationship with him. This idea is shown in Figure 06. In Figure 06A the opponent grabs Master Chen. In Figure 06B, Master Chen reminds stationary despite the advance until in Figure 06C Master Chen executes a technique to cause his opponent to fall down. |

|

He compared this to the chaotic nature of simultaneous movement: “If I move and you also move at the same time, we always miss each other. So we say that a moving object cannot be hit.” The core idea is that by maintaining stillness, one creates a fixed reference point, making the opponent the sole moving object that can then be controlled and struck.”

Combat Strategies

Master Chen began by using the analogy of a sniper in a battle to explain the strategic difference between common movement tactics and the Practical Method of fighting. He first stated a common military principle from Guerrilla Warfare Strategy (游击战):

|

“In Chinese, we say, ‘Every time you fire, you change to a different place‘ [打一枪换一个地方; dǎ yī qiāng huàn yī gè dì fāng; shoot one gun (shot), change one place]. Right?” Master Chen explained that this phrase, which gained immense cultural and historical currency during the Chinese Civil War and the Sino-Japanese War, is based on survival: “Because if you stay in the same location, the sniper will find you. So moving is a good idea in that case so they can’t find you.” |

However, Master Chen immediately posed the central problem of constant movement when both parties are mobile: “But fighting is you need to find your opponent. You can’t fight not knowing where your opponent is.”

This presents the basic dilemma in fighting: Not moving means you risk being hit, but moving means you risk missing or never establishing the point of contact needed for a successful technique.

The Practical Method offers a solution by adopting the strategy of the sniper, choosing to be the stationary anchor rather than the moving target. This approach is rooted in two classical Chinese military philosophies:

| 1. Calculated Risk (High Reward): The method follows the Chinese proverb attributed to General Ban Chao (班超) of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 AD to 220 AD): “If one does not enter the tiger’s den, how can one obtain the tiger’s cub?” (不入虎穴,焉得虎子, Bù rù hǔ xuè, yān dé hǔ zǐ). This means one must take a calculated risk by electing not to move—choosing to be the target’s location, or “den”—in order to achieve the great reward of the decisive strike. |

|

|

| 2. Yin-Yang Stillness and Action: This sniper strategy is formalized by the maxim found in The Art of War (《孙子兵法》)/ by Sun Tzu, specifically summarized from the Chapter “The Nine Varieties of Ground” (九地篇 – Jiǔ Dì Piān): “Still (calm) like a virgin (young maiden), moving (active) like a startled/cunning rabbit.” (静若处子,动若脱兔, Jìng ruò chǔ zǐ, dòng ruò tuō tù). |

|

The Practical Method thus requires you to first master the “Yin” or stationary component—being perfectly still and composed while waiting—and then, when the opponent commits, immediately explode into the “Yang” or moving component with decisive speed.

Master Chen concludes “[In the Practical Method] the procedure is reversed [from commonly perceived notion of martial arts training. Instead of training for speed and endurance, the bases of movement, you need to focus on stillness. That] is you lock a spot then your training has meaning. By doing that your body gets the exercise. When your body gets the [correct] exercise, in the end your body is free. so meaning that ultimately [for Taijiquan] either it’s a martial art or an exercise, you need some stretching.”

Master Hong’s work on the Lever

Master Chen’s introductory lecture serves as a powerful continuation of the foundational teachings established by his revered teacher, Master Hong Junsheng. The core of this legacy lies in the dual concepts of the Lever (杠杆, Gànggǎn) and the Circle, the mechanical bedrock of the Practical Method. Master Chen beautifully summarized these mechanical models not as mere physics, but as tangible expressions of the fundamental Taoist principle of Yin-Yang separation in action.

Master Hong extensively utilized the lever analogy to dissect the application of jin (force or energy), offering a precise, repeatable method for understanding power generation and redirection. His insights detail the body’s structure as a system of levers, with the dantian/waist acting as the effort or primary driver, the point of contact with the opponent as the resistance, and various joints—particularly the kua (hip) and shoulder, serving as crucial, adjustable fulcrums.

Master Hong’s own words convey the essence of this mechanical understanding, particularly in relation to the Eight Methods:

|

“Peng Jin is the first of the Taijiquan Eight Methods and is the most fundamental jin… Its form is like an arch bridge, able to withstand pressure from above, below, left, and right… Its mechanical structure is that of a lever.”

(“掤劲是太极拳八法之首,也是太极拳最基本之劲… 它的形象如一座拱桥,能承受从上、下、左、右来的压力… 它的力学结构是杠杆。”) |

|

This profound insight elevates Peng from a simple arm posture to the foundational, outward-expanding force—a lever being effectively pried open.

Similarly, he explained the strategic technique of Lu (Rollback) through this lens:

|

“The Lu method… uses a small force to move a large force. It uses the principle of the lever to change the direction of the opponent’s force.”

(“捋法… 是用小力拨动大力,是以杠杆原理,改变对方劲力的方向。”) |

|

The mechanics of Lu, therefore, are an art of leverage, skillfully shifting the fulcrum to redirect an opponent’s force with minimal effort.

Master Chen’s lecture ensures that the mechanical brilliance of Master Hong’s lever principle remains the indispensable key for all serious practitioners of the Practical Method. This principle finds its direct, physical manifestation in the drawing of the Positive Circle and the strategy of remaining still during combat.

The Circle represents the path of force that maximizes leverage, and its structured practice comprehensively develops the four Primary Energies of the Eight Methods:

|

|

Furthermore, Master Chen’s Three Nails are the structural anchors or fulcrums required for this leverage. The combat strategy of stillness at the center of a martial exchange is the ultimate mastery of the fulcrum—a fixed point from which devastating power or deft redirection can be instantly deployed. Thus, the lecture brilliantly ties the circle’s detailed methodology to the overarching principle of mechanical clarity.

2. Wheel (轮) and Spinning Disc (转盘)

Based on the video Master Chen Zhonghua Peng / Lu / Ji / An. Dec 12, 2020.

|

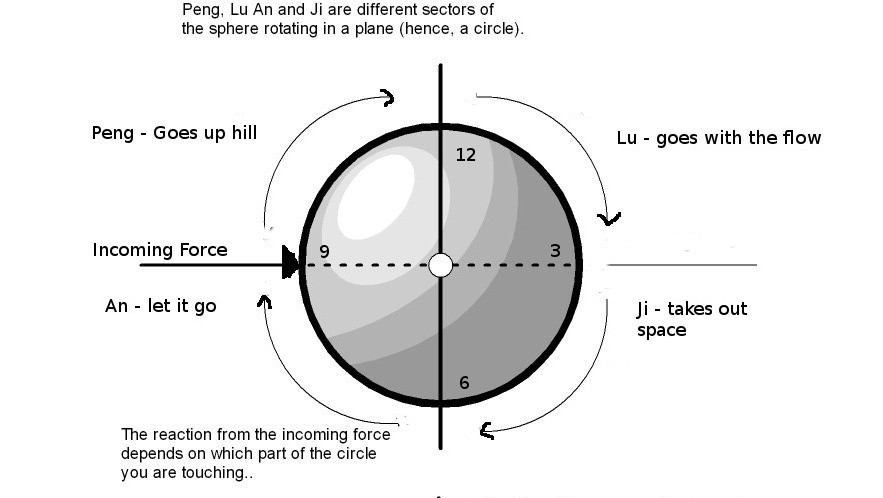

Master Chen sketches a precise diagram of a circle on a whiteboard, immediately dividing it into four equal quarters. He uses the familiar reference points of a clock face to determine the location of each quarter.

This configuration means the first quarter spans from 9 o’clock moving up to 12 o’clock; the second quarter extends from 12 o’clock down to 3 o’clock; the third quarter covers the arc from 3 o’clock to 6 o’clock; and finally, the fourth quarter completes the circuit by moving from 6 o’clock back to 9 o’clock. This diagram is reproduced in Figure 07. |

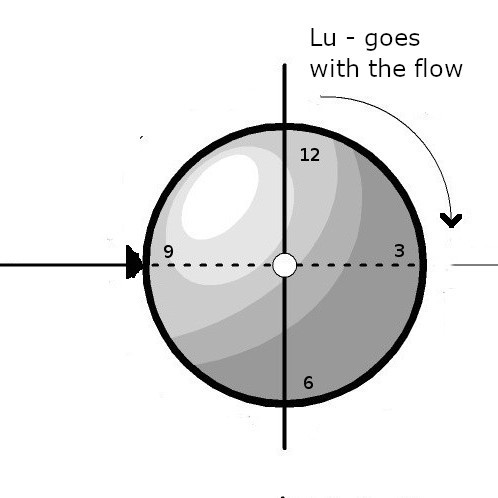

| Master Chen introduces the circle as a two-dimensional mechanical model designed to illustrate the core concepts of the first four Primary Energies (正勁, Zhèng Jìn) within the Eight Method of Taiji (Bamen). He later extends this concept, using a sphere as a three-dimensional mechanical model, to explain the remaining four Four Diagonal Energies (隅勁, Yú Jìn). Gesturing toward his drawing, Master Chen declares, “This is a solid disc [or wheel],” and outlines its fundamental assumptions: the central axis remains fixed and immovable, though the disc itself is free to rotate clockwise. Crucially, the circle’s perimeter is presumed to be structurally indestructible. |

|

The First Quarter: Peng (Ward Off)

|

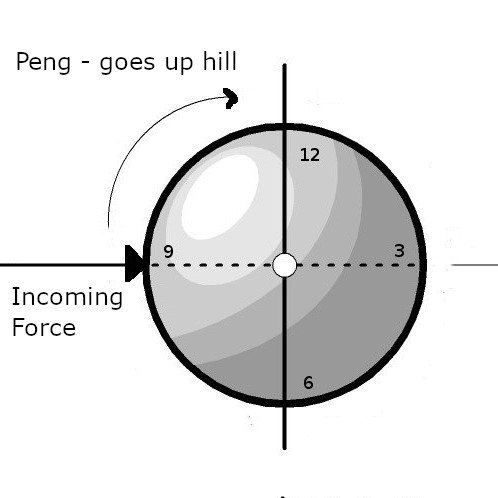

Master Chen then illustrates an incoming force by drawing a straight arrow at the 9 o’clock position, aimed directly at the fixed center of the circle. He explains, “When you strike this wheel precisely on the center here [at 9 o’clock], the incoming force immediately encounters immovable resistance, and the wheel does this: [it forcefully bounces back because the perimeter cannot be destroyed].”

To emphasize the powerful, elastic rebound, Master Chen physically executed a sharp, recoiling jump backward. He clarifies, “That instantaneous, resilient ability to resist and reflecting a hit is called the Peng energy.” |

Master Chen continues his explanation: “If you strike it [the circle] but your point of impact is slightly off [away from the] center, the force is not absorbed but is instead deflected, or driven along this entire [first] quarter [of the circle, spanning from 9 o’clock to 12 o’clock].”

He stresses that [This first quarter] is [governed by the technique of] Peng. He reiterates that the initial action is a direct [and very hard] hit on the circle, but since the impact cannot break through the perimeter of the circle, the force is immediately redirected and drive up [along the perimeter of the circle towards the 12 o’clock position], turning the strike into an upward deflection or ‘roll-off’.

Master Chen utilizes this initial quarter to lay the groundwork for understanding how Peng (膨) functions not merely as direct resistance, but as an expansive, outward-rolling energy that both protects the center and redirects incoming force. Colloquially, the sensation of Peng is often likened to moving uphill.

Master Chen now moves to describe the second section of the mechanical model, the arc following the initial Peng energy.

The Second Quarter: Lu (Rollback)

|

He states, “Once you reach here [the section of the circle between 12 o’clock and 3 o’clock, you immediately experience] this sinking, dragging feeling [of being pulled towards the wheel’s center or direction of rotation.]”

To make this description more explicit, Master Chen describes the action of a rotating wheel. “If you have a wheel turning here [clockwise from 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock], and you touch here [the back or receding side of the wheel’s perimeter in the second quater of the circle], it does this: [it hooks your hand or body and drags you towards the wheel’s direction of travel.] That [technique of yielding, guiding, and drawing inward] is called [Taiji technique of Lu] ‘Rollback‘.” |

Master Chen reinforces the sensation by pointing back to the circle on the whiteboard: “Imagine standing here [at the original 9 o’clock position] and trying to touch the perimeter somewhere between 12 and 3 o’clock.” He explains that the wheel’s clockwise rotation creates a force that “pulls” the hand, capturing and immediately redirecting the energy. This entire action, from the point of contact to the redirection of force, is governed by Lu (捋, Rollback). The concept’s essence is often described simply as “going with the flow.”

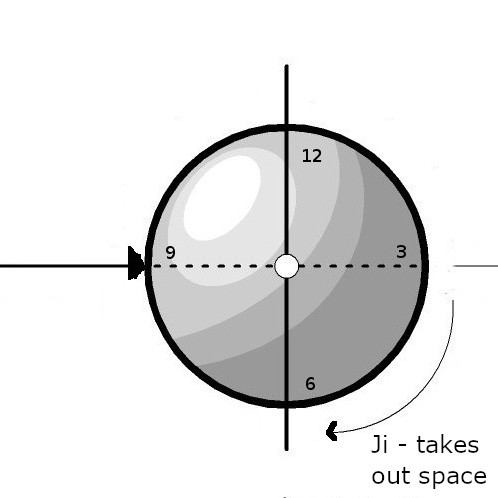

The Third Quarter: Ji (Press)

|

Master Chen then continues to the next section of the circle, pointing to the area between 3 o’clock and 6 o’clock. “This area is Ji. Ji is anything that assertively takes up space.”

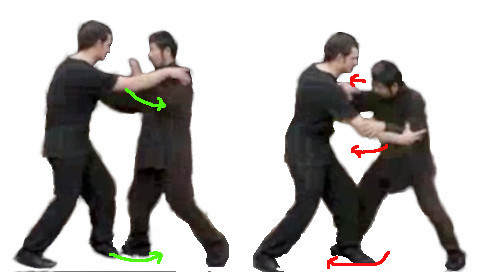

Master Chen then demonstrates the transition of these concepts with his student to provide practical context. He begins by establishing the initial contact: “So when I touch him here, or you touch me.” Master Chen places one hand on the back of his student’s back, while his student places two hands touching Master Chen’s chest or body. “See, this is Peng,” he says, describing the initial position where the student is kept at an engaged, yet arms-length distance, representing the ability to resist or neutralize. |

When Master Chen deliberately pulls his student’s back towards him and off-balance, he describes this action: “This is Lu [drawing the opponent inward and off-center].” Master Chen then allows his student to attempt to counter his pull, saying, “But I cannot [perform the technique of] Lu [on] him; he’s too strong.”

| Master Chen changes his approach to transition from Lu to Ji. He moves closer to the student by stepping and moving his body between the arms of his student, physically asserting himself into the gap. He explains this critical action, saying, “I take over this space [that is immediately between me and my opponent’s body]. That [technique of compression and forceful entry] is Ji.” The example of Ji is shown in Figure 08 with the green arrows showing the action of taking up empty space. |

|

To emphasize the mechanical circle model once more, Master Chen points to the area between 3 o’clock and 6 o’clock as the section representing Ji, concluding the demonstration by repeating the core definition: “So you take up this [empty, contested] space [between me and my opponent].” Master Chen concludes his analysis of the mechanical model by focusing on the final quarter.

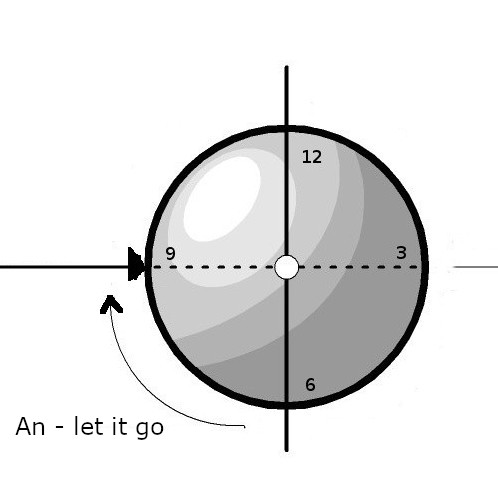

The Fourth Quarter: An (Press)

|

Master Chen points to the last section of the circle, spanning the arc between 6 o’clock and 9 o’clock, saying, “The last one here [section of the circle, describes the technique of] An (Press Down). It is [a technique executed] when your opponent is already in motion and on the decline [or retreating].” An capitalizes on the opponent’s instability created by the preceding techniques (Peng,Lu,Ji). A simple understand of An is that the technique is based on “letting go“. |

Master Chen then provides a practical demonstration of this definition with a student. The student grasps Master Chen’s body or arms with both of their hands (simulating a solid point of contact). Master Chen, rather than resisting directly, places his hands strategically behind the student’s back or shoulders and applies a downward, forward pressure.

|

The student immediately yields and moves down and away due to this coordinated pressure, signifying a loss of balance and root. This action is shown in Figure 09 with the green arrows showing the movement of the student as the result of Master Chen’s actions.

Master Chen explains the critical timing of the technique: “He is already on the decline here. [The technique of An requires] you [to continue to] go with him—to accompany his fall—and smoothly send him down [and away, until your opponent is no longer in stable contact with you].” |

|

The essence of An is not just to push, but to seal the opponent’s fate by integrating one’s force with the enemy’s momentum until they are thoroughly routed. Master Chen concludes his explanation by summarizing the four fundamental Taiji techniques (Peng,Lu,Ji,An) through the lens of the mechanical circle model.

The Dynamic Cycle

He synthesizes the actions demonstrated in each quarter: “So, there is bouncing [Peng, or expansive resistance]; there is a following [Lu, or drawing-in, redirecting force]; there is going closer [Ji, or pressing into and asserting space]; and there is separation [An, or pushing down and rooting out the opponent].”

He emphasizes the structural importance of this group: “Those are the four cardinal [directional] energies of Taiji. We give them different names for different energies.”

Finally, Master Chen brings the concept back to its geometric origin: “In the end, it’s all derived from a single principle: the rotation of this wheel, and where you [make contact or] grab [or touch the perimeter of the circle] relative to that rotation.” This clarifies that the four techniques are not isolated moves, but four necessary phases experienced as a force interacts with a rotating, resilient body.

Master Chen now moves to extend the simple, two-dimensional model to account for a more complex, three-dimensional application of the Taiji principles.

From Vertical Wheel to Horizontal Disc

|

The circle drawn on the whiteboard primarily described the action of a wheel undergoing vertical rotation (like a Ferris wheel or a bicycle wheel), illustrating how an incoming force is managed on a vertical plane.

Master Chen suggests extending this mechanical analogy to three dimensions, stating, “So, you can conceptualize this energy rotation as a horizontal flat disc [or platter] instead of a vertical wheel.” |

He emphasizes that the fundamental principles remain consistent: “The reaction experienced upon touching the rotating disc [ Spinning Disc (转盘)] is precisely the same, only translated into another dimension [the horizontal plane, rather than the vertical].” This confirms that Peng,Lu,Ji, and An apply universally, governing all rotational movements whether they occur up-and-down (vertical) or side-to-side (horizontal).

Master Chen offers a more granular distinction between the two forward-driving techniques, An (Press Down) and Ji (Press/Squeeze), emphasizing the resulting outcome of each action.

Distinguishing An and Ji

He explains the fundamental goal of An: “An is a push that creates a separation and removes the opponent from your sphere of control. [In contrast,] a push that does not create a separation but rather maintains engagement and applies concentrated force is called Ji [which] means squeeze or compression.”

This distinction is crucial: Ji is about maintaining contact and asserting control over contested space, while An is about releasing contact by sending the opponent away and down.

Tactical Application: Ji as an Entry Strategy

Master Chen then presents a practical series of techniques, illustrating how a martial artist must transition when primary strategies fail.

He sets up the scenario: Imagine a strong opponent stands before you. You are attempting to neutralize their incoming force using the Peng technique, but you can barely keep them at bay. You then try moving them sideways with Lu (Rollback), but your opponent is too stable and is not advancing or yielding.

Master Chen then explains the essential shift in strategy: “If I cannot [use the method of] Lu [(roll back) to lead] you away or [make you] off-balance, I have to change my approach. I just go like this [he closes the distance and drives his mass into the space previously separating them, often using the shoulder or back], and take up the space between me and my opponent. This technique [of assertive, space-claiming entry] is a squeeze (Ji).”

He describes the immediate continuation of the technique after successfully establishing Ji: “Once I have compressed you, I then follow through and execute An [a technique that results in a definitive separation]. You’re gone,” he states, emphasizing the conclusive nature of the final downward push that sends the opponent away and ends the engagement. The sequence highlights that Ji is often a necessary intermediate step to secure position before the final, separating force of An can be applied.

Master Chen concludes his explanation by reiterating the core principle derived from the mechanical circle model, moving from the specific techniques back to the unified concept of rotation.

The Four Cardinals as Rotational Outcomes

He restates the four cardinal techniques: “This is the four cardinal ones: Peng,Lu,Ji,An. It’s a hit/bounce (Peng), it’s a pull/draw (Lu), it’s a stepping in/squeeze (Ji), and it’s a separation/press (An).”

He emphasizes that these varied physical results are not separate, intentional moves: “So, all those things, you can see, are all results of different touches in different positions [on a rotating disc] because of the different phases of its revolutionary or rotating directions. The underlying energy is always the same.”

The Illusion of Intentional Technique

Master Chen challenges the common perception of Taiji practice: “Now you understand? You cannot intentionally create [the reaction]. [The common notion in Taiji is that you are training an action. For example,] ‘I’m rolling on you,’ or ‘I’m pushing you,’ or ‘I’m squeezing you.’ [From the perspective of the Practical Method,] it’s none of that.”

He clarifies that the effectiveness comes from the structure and rotation of one’s own body: “You just rotate. When you’re rotating, your opponent touches you on two spots, he will immediately be in trouble, because one spot feels like pushing (Peng) while another spot feels like pulling (Lu). [As a result of this conflicting feeling,] he does not know what to do.”

This dilemma for the opponent is the key: “All of those [conflicting feelings] come from the same single energy: rotating. That is why you never try to hold a rotating disk.”

Final Analogies of Rotational Force

Master Chen provides rapid, descriptive analogies of interacting with rotation to cement the idea:

|

|

The lesson is that the four cardinals are simply the inevitable reactions an opponent experiences when they try to fixate or control a perfectly rotating, spherical structure—the martial body.

Master Chen concludes his discussion by generalizing the experience of the opponent, explaining why the simple act of internal rotation creates varied, confusing reactions for anyone who makes contact.

The Goal: Creating Rotation, Not Applying Force

He emphasizes that the core task of the practitioner is internal, not external: “So, our job is simply to create a rotation within our structure. When you can rotate, and your opponent touches you, every single person who touches you will tell a different story because it’s not possible to touch exactly the same two spots.”

He illustrates this concept using an anecdotal example from teaching: [Different students touch me as I perform a Taiji technique,] and their immediate perceptions clash. When the spots [the points they touch on my body] are at a little bit different [location], [one student] will say, “‘Oh, Master Chen is very strong, [I felt a powerful, outgoing Peng energy]’.” [Another student] from a slightly different position will immediately counter, “No, no. I’ve worked with Master Chen for a long time. [The technique is] not strong; it’s very, very empty [I felt a sudden Lu or yielding emptiness].”

Understanding the Conflicting Viewpoints

Master Chen explains this dramatic contrasting view based on the concept of the rotating circle:

|

|

The profound lesson is that the practitioner is not doing four different things; the practitioner is performing one consistent rotation. The four cardinal energies (Peng,Lu,Ji,An) are simply the four possible perceptions of that single rotating body, depending entirely on the opponent’s unstable point of contact.

Master Chen concludes his entire teaching by explaining the perceived “mystery” of Taiji and the Practical Method, rooting it firmly in the physical reality of the rotating structure.

The Lack of Consensus

He states, “That’s why Taiji is very mysterious, because [the physical result] is real and undeniably effective. Yet, for every person touching [the technique], it feels completely different. You cannot come to a consensus [on what the Taiji person is doing] because [a circle has] 360 degrees of continuous, rotating possibilities.”

This concept—that a single action (rotation) produces a multitude of reactions (Peng,Lu,Ji,An and everything in between)—is what confuses observers and opponents alike.

The Rhetorical Challenge

Master Chen ends with a powerful rhetorical question, challenging the students to abandon the pursuit of fixed techniques and embrace the dynamic nature of the body: “During a continuous rotation, where are you touching [on that circle]? How can you guarantee you’re touching the same spot all the time?”

This question underscores the fundamental lesson: The Taiji master is not trying to hit a specific target or execute a named move; they are simply maintaining an active, rotating structure. The opponent’s varied experiences—of being pushed, pulled, squeezed, or bounced—are entirely dependent on the random, shifting point of contact relative to that immutable, moving whole.

The Perpetual Engine of Taijiquan

Master Chen’s introductory lecture on the rotating wheel (轮, lún) offers a clear, mechanical blueprint for understanding the complex power generation of the Practical Method of Taijiquan. This deceptively simple model is the foundation upon which the entire system is built, revealing that the celebrated Eight Methods are not a mere collection of movements but the direct expression of an internal, perpetual rotation.

The lecture’s success lies in translating the abstract concepts of Yin-Yang and the Cardinal Energies into simple mechanical models of the rotating wheel and spinning disc. Master Hong Junsheng, whose intricate theory informs this model, stresses that the source of Taiji’s unique power is fundamentally rotational, not linear.

This theoretical nexus originates in the teachings of Master Hong Junsheng, whose core statements serve as an enduring mandate for our Taijiquan practice and reveal the true power of the Practical Method:

|

“The power of Taijiquan is fundamentally rotational. The waist and hips are like the axle of a cart, the hands and feet are like the spokes of the wheel. When the hand extends, the elbow does not [fully] extend; when the elbow retracts, the hand does not [fully] retract. It is like the rotation of a wheel, with the power unceasing.”

(“太极拳的劲力以旋转为根本,腰胯如车轴,手足如轮辐。出手不出肘,收肘不收手;如同车轮之旋转,劲力绵绵不绝。”) |

|

This mandate is a succinct instruction on the concept of whole-body connectivity and the signature Chan Si Jin (缠丝劲), or silk-reeling energy. It reminds us that our limbs must act as coordinated extensions of the central axle, maintaining continuous tension and rotation rather than succumbing to the static, fully extended lockouts of linear force. This unceasing, rotational dynamic is the source of the method’s renowned flowing power.

Extending this foundational model, Master Hong further elucidates a more complex explanation of the Four Cardinal Energies (Peng, Lu, Ji, An) with focus on applications of the wheel’s dynamic and not just on the simplfy energy characteristics:

|

|

The most critical takeaway—and the ultimate practical application of this wheel model—concerns the true origin of our explosive force, or fajin (发劲). Master Hong emphatically separates the point of release (the hand or foot) from the point of initiation (the waist and kua):

|

“Issuing power is like releasing an arrow; the arrow is released from the rim of the wheel. It is not the power of the hand, but the rotation of the waist and kua that flings the hand out with power.”

(“发劲如放箭,箭从轮缘出。非手之劲,乃腰胯旋转,将手甩出之劲。”) |

|

This principle is the master key to the Practical Method. It compels us to shift focus away from muscle-driven punching and pushing and toward cultivating the rotation of the axle as the primary engine. When properly executed, this circular rotation transforms the hand from a source of limited, localized force into the final point on a powerful, accelerating flywheel, capable of releasing tremendous kinetic energy.

By providing this mechanical analogy, Master Chen has illuminated not just what the Eight Methods are, but how they fundamentally function. Our ongoing task is to internalize this wheel, making the unceasing, rotational movement of the axle the intuitive core of every Taijiquan technique.