|

This essay is the second installment detailing Master Chen’s direct, practical approach to explaining the complex structure of the Eight Methods of Taijiquan. Drawing specifically from his 2014 Toronto Workshop lecture and reinforced by the essential wisdom of Master Hong’s writings, this analysis represents a clear, direct application of the Practical Method learning system.

Previously, we established the nature of the Primary Energies (正勁 – Zhèng Jìn)—the most obvious, linear, and final expressed power (发劲 – Fā Jìn) of a technique. Now, we turn our focus to the crucial second section: the Four Diagonal Energies (隅勁 – Yú Jìn). |

| This essay will dive into this ‘subtle process‘ of leading, neutralizing, and storing energy — the indispensable Yú Jìn. By exploring the mechanics of these diagonal, transitional forces, we will uncover exactly how they function as the foundation for leading, deflecting, and storing the immense power that makes the final, direct Primary Energies truly devastating. | |

| (This is article based on the Eight Techniques mini-lesson filmed in 2014, Toronto, Canada.) |

|

The mini-lesson continues to answer the question: “What is the Eight Methods of Taiiquan?”

|

|

Introduction

Part 1. Four Primary Energies (正劲)

Part 2. Four Diagonal Energies (隅劲)

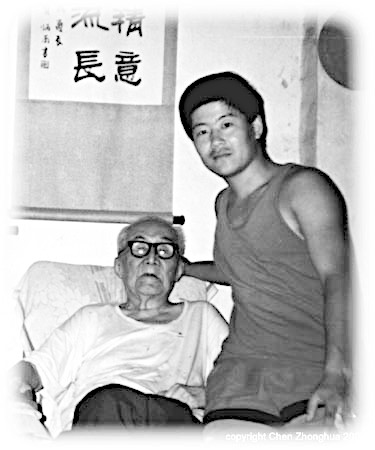

Master Hong Junsheng’s work, particularly his Practical Method of Chen Style Taijiquan, offers a vital framework for understanding the martial applications of the art. He made a critical contribution by clearly dividing the Eight Methods (Bā Fǎ or 八法) into two complementary sets: the Four Primary Energies (Zhèng Jìn 正劲) and the Four Diagonal Energies (Yú Jìn 隅劲).

Together, these two groups form a foundational dialectic for mastering practical application (Yòngfǎ 用法). Simply put, they explain the complete mechanical and tactical theory behind how and why Taiji techniques work.

The Four Diagonal Energies (Yú Jìn 隅劲) are often misunderstood, but Master Hong’s explanation brings them into sharp focus. The Chinese word “隅” (Yú) literally means “corner” or “nook.” In his system, it refers to the four diagonal directions that exist between the four cardinal directions (North, South, East, West).

The four techniques classified as Yú Jìn are:

|

|

Master Hong defined these four methods as “diagonal” energies because they are typically applied at angles (e.g., Cǎi is a diagonal, downward pluck). However, his most profound insight is that they are not just “attacks” but are the essential, preparatory movements that make the Primary Energies effective.

In Master Hong’s teaching, the Yú Jìn is the auxiliary energy that creates or resolves a situation. He states they are often used as more specialized, explosive applications or responses that arise from the context created by the Four Primary Energies.

He emphasized a core principle: The Diagonal Energy is the storing of power, not the release.

The Yú Jìn is the “yin within the yang” — the essential coiling movement or subtle control that precedes and enables the final strike. It represents the crucial concept of Storing Energy (Xù Jìn 蓄劲) that must occur before the explosive Releasing Energy (Fā Jìn 发劲).

Master Hong argued that a single, fixed, forward-moving direction is insufficient for practical application in a dynamic fight. He posited that every primary technique contains a “seed” or a preparatory movement in a different, often opposite or complementary, direction.

This is best summarized by his famous principle:

“To go straight, first turn; to go forward, first retreat.”

The Diagonal/Secondary energy (Yú Jìn) is precisely this initial “turn” or “retreat.” By defining this concept, Master Hong provided students with a complete, mechanical roadmap: the initial diagonal movement creates the tension, leverage, and momentum needed for the final, devastating, primary-direction strike.

5. Cǎi (采)

Cǎi (採), often translated as “pluck” or “snap,” is renowned for its swift and decisive ability to uproot an opponent. It is a brilliant example of using short, sharp jìn (勁) to immediately break an opponent’s structural integrity.

Master Hong’s description captures the explosive precision and holistic nature of this method:

|

“Cǎi is the method of using the hand to quickly seize the opponent’s wrist or elbow and, using the coordinated power of the waist, jerk it downward in a sudden, sharp manner. It is like a skilled fruit picker plucking a piece of fruit with a quick, snapping motion—swift, precise, and intended to break the connection. Its power is short, explosive, and follows a diagonal path.”

(“採是以手快速拿住对方腕部或肘部,利用腰的协调力量,突然、短促地向斜下方抖拽的方法。好似熟练的果农采摘果子时快速摘下的动作——迅速、精准,意在断其根。其劲力短促、爆发,走的是斜线。”) |

|

The effectiveness of Cǎi is dependent on the precise integration of jìn and body mechanics:

|

The goal of Cǎi is instant uprooting and structural collapse, creating a vulnerability for follow-through techniques. By seizing a joint and executing the diagonal snap, you effectively pull one component out from under the opponent’s centralized structure. This sets them up perfectly for techniques like a close-range Zhōu (肘), a directional Liè (裂), or an immediate throw using Jì (擠). A successful Cǎi is swift, surgical, and relies on the unified coordination of the entire Taiji body.

Cǎi Mini-Lesson

|

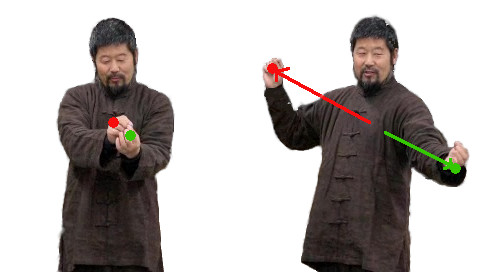

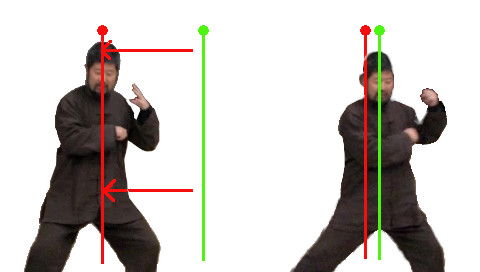

Master Chen begins the technique with his hands held close together in front of his chest, as shown by the red and green dots in Figure 01. He then simultaneously separates his hands at an angle, performing a split motion. The right hand travels upward and outward to the top-right position (analogous to 10 o’clock), while the left hand moves downward and outward to the bottom-left position (analogous to 4 o’clock). The paths of movement are depicted by the colored arrows in Figure 01. Master Chen summarizes this powerful, opposing split—the essence of separating the two fundamental forces—with a precise term: “When you split Yin-Yang this way, it’s Cǎi (採)..” |

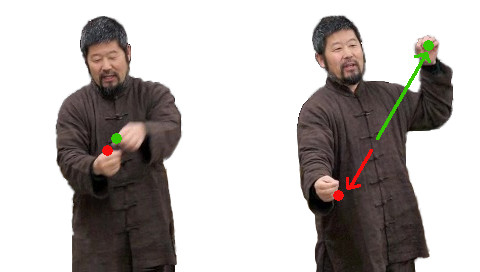

Master Chen demonstrates the technique of Cǎi (採) with a student. The demonstration begins as the student reaches forward with their left hand to grab Master Chen’s right hand. Master Chen intercepts this action with his right hand by immediately seizing the student’s wrist—an action that represents the Swift Seizure (Ná 拿). This initial engagement is shown in the first panel of Figure 02.

|

Master Chen identifies two critical anchor points: the student’s left shoulder as one stationary point, and the grip on the wrist as the second. These anchors are highlighted by the red and green dots in the middle panel of Figure 02.

Master Chen initiates the Cǎi (Pull-down) technique by subtly adjusting his balance and dropping his center. The power is generated internally: his dantian rotates forcefully, transferring the structural stability from his front stance to his rear. The wrist acts as the lever, driving a diagonal downward action. |

|

The result is a sudden burst of power known as Dǒu Zhuài (抖拽)—an explosive, snapping energy that violently pulls the student forward and compromises their joint structure. Master Chen himself succinctly articulates the mechanical principle:”I go like this here [yank on the grip on the wrist, as a result] I sever here [at the stationary point at the shoulder.]”

In the final panel of Figure 02 (highlighted by the red arrow), the sudden, leveraged pull causes the student to literally jump, demonstrating the “severing” of their structural connection to the ground. The technique momentarily breaks the integrity of the opponent’s frame at the shoulder, achieving structural collapse rather than mere displacement.

6. Liè (挒)

Liè (挒), frequently translated as “Split,” or “Tear,”is a potent martial force that goes beyond a simple diagonal push. Its true essence, as emphasized by Master Hong, is one of torsional, rending energy. It is the strategic principle of dividing and conquering the opponent’s unified posture.

Essentially, Liè is a lateral tearing motion that targets and fractures the opponent’s incoming force. It works by applying a powerful counter-force—forces moving in diametrically opposite directions—to the opponent’s structure. This simultaneous opposing action inflicts a severe and sudden imbalance, immediately opening pathways for decisive follow-up techniques. Applied with full intent, this torsional force can even severely strain or injure joints by literally tearing their mechanical connections apart.

The defining characteristic of this method is the simultaneous, opposing action that breaks the opponent’s structural continuity. Master Hong clearly captured the devastating precision of this jin (energy)::

|

“Liè jin is a kind of tearing force… The two hands exert force in opposite directions, like tearing silk or breaking cloth… Liè jin must be crisp, emitting power through rotation, injuring their joints and separating their limbs.”

(“挒劲是一种撕裂劲,……两手反向用力,如撕绸断布,……伤其关节,分其肢体。”) |

|

Master Hong’s definition provides the roadmap for internalizing and applying Liè effectively:

|

Liè Mini-Lesson

|

Master Chen begins the technique with his hands held close together in front of his chest, as shown by the red and green dots in Figure 03. He then simultaneously separates his hands at an angle, performing a split motion. The right hand travels downward to the bottom-right position (analogous to 7 o’clock), while the left hand moves upward to the top-left position (analogous to 2 o’clock). The paths of movement are depicted by the colored arrows in Figure 03. Master Chen summarizes this powerful, opposing split—the essence of separating the two fundamental forces—with a precise term: “When you split Yin-Yan this way, it’s Liè (挒).” |

| Master Chen’s demonstration of Liè (挒), the ‘Split/Diagonal Splitting‘ technique, begins by establishing critical structural anchor points on the student’s left arm. With precise control, Master Chen takes hold of the arm, gripping the student’s left wrist with his own left hand and placing his right hand on the left elbow. He visually identifies the two anchors fundamental to the technique: the student’s left shoulder acts as the stationary pivot, and the elbow serves as the active, manipulable point. These two vital spots are highlighted, respectively, by the red and green dots in the first panel of Figure 04, marking the initial, poised position. |

|

The actual application of Liè is a masterclass in exploiting an opponent’s natural reflex. It doesn’t start with brute force but with a calculated lure: Master Chen applies a subtle, diagonal pull downwards on the arm. This action is specifically designed to elicit the student’s instinctive counter-force, causing the student to flex their left elbow to resist the pull. This moment of counter-tension is instantly exploited: Master Chen follows through with a sudden, decisive Fa Jin (發勁, explosive power), pushing the left elbow directly towards the shoulder anchor. This simultaneous application of opposing directional forces—the student’s reflex pull versus Master Chen’s push—is the core mechanism that causes the structural disruption described by Master Hong. The middle panel of Figure 04 illustrates this intermediate stage, showing the elbow anchor (red dot) being driven along the vector (red arrow) toward the stationary shoulder, effectively compromising the student’s joint and root.

The technique culminates in a decisive, unified action that targets the opponent’s joints. Rather than relying on mere arm strength, Master Chen executes a whole-body rotation driven from his Dantian (as elucidated in the final panel of Figure 04). This unified rotational power translates the focused force of Liè (Splitting) through the student’s already compromised structure.

Master Chen precisely details the mechanism of structural failure: “Liè is a break in the middle here [at the elbow.] He has to move [forward] to get out of [the rotational power of the Dantian.] If I go fast without him moving, this [middle section, the elbow] is broken. [Liè is explosive. The technique does not] give you the time to let go.”

Rooted in Dantian rotation, this irresistible, unbalancing force causes the student to lose root and stumble forward. The final outcome, shown in the final panel of Figure 04, is a sudden, explosive application that leaves the student literally falling, a consequence of the mechanical “break” in their structure that prevents the targeted, more destructive breakage at the elbow joint.

7. Zhǒu (肘)

Zhǒu (肘), conventionally understood as a percussive “elbow strike” applied in close quarters, undergoes a radical reinterpretation within the lineage of Master Hong Junsheng’s Practical Method. This fundamental shift redefines Zhǒu from a literal body-part technique to an essential principle of rotational force (Niǔ Jìn 扭勁).

Master Hong grounds this redefinition in a linguistic correction rooted in the local Chenjiagou (陈家沟) dialect of Henan Province (河南). He posits that Zhǒu (肘, elbow) is a homophonic misunderstanding of Niǔ (扭, to twist). Therefore, Zhǒu Jìn (肘劲, elbow energy) is properly understood as Niǔ Jìn (扭勁, twisting energy).

The core principle is not the impact of the elbow but the application of a controlled, spiraling, and leveraging force generated by the winding of the forearm and focused at the elbow as a pivot point. The focus is on seizing and structural disruption, not percussive collision. Master Hong’s full statement serves as both a correction of common misunderstanding and the linguistic foundation for his thesis, directly linking the principle to the oral tradition of Chenjiagou:

| “The elbow method in Chen-style Taijiquan does not refer solely to striking with the point of the elbow. Rather, it contains the energy of winding, wrapping, and twisting. In the Chen Village [Chenjiagou] dialect, ‘Zhǒu’ (肘) and ‘Niǔ’ (扭, to twist) have similar pronunciations. Hence, there is the saying that the ‘Zhou Jin’ (肘劲 elbow energy) is actually ‘Niu Jin’ (扭劲 twisting energy). Those who study this should understand this principle so as not to misunderstand the method.”

(“陈式太极拳的肘法,并非仅指用肘尖顶击,而是含有缠绕、裹挟、扭转之劲。在陈沟方言中,‘肘’与‘扭’音近,故有‘肘劲’实为‘扭劲’之说。学者当明此理,方不致误解其法。”) |

|

This pivotal passage compellingly redirects the practitioner’s intention by clarifying the initial “misunderstanding” (误解). It compels a shift in focus from the body part (the elbow) to the core internal actions of winding (chan rao 缠绕), wrapping (guo xie 裹挟), and twisting (niu zhuan 扭转).

|

For Master Hong, Zhǒu (肘) is a sophisticated mechanism of rotational control, prioritizing subtle, coiling twisting energy (Niǔ Jìn) over direct impact to exemplify the core Taiji strategy of using softness and internal mechanics to overcome hardness and external strength.

Zhǒu Mini-Lesson

|

The technique begins with Master Chen’s hands positioned precisely in front of his body, capturing the initial state of separation (the first panel of Figure 05). The right hand, marked by the red dot, is held at shoulder height, representing the ascendant force. Conversely, the left hand, indicated by the green dot, rests at hip level, embodying the grounding force. This dual-level setup establishes the vertical axis of the opposing movement. |

From this poised beginning, the action becomes a unified, simultaneous, and circular exchange: the right hand descends as the left hand ascends, tracing circular paths (indicated by the curved arrows toward the second panel of Figure 05). This controlled, fluid counter-movement generates a powerful, opposing twist separating the two fundamental forces, Yin and Yang, around a common center.

Master Chen distills the deep, intrinsic energy of this action into a single, precise term, revealing its true application: “When you split Yin-Yan this way, it’s Zhǒu (肘).”

Master Chen begins his elaboration on the term Zhǒu (肘), drawing directly from the teachings of Master Hong Junsheng. He immediately frames the original meaning as a core, yet often neglected, concept:

“Zhǒu is like a steering wheel, and we do a lot of that. It’s a primary action that’s lost in Taiji.”

Master Chen then contrasts this with the prevailing modern interpretation, acknowledging the common knowledge: “[The Eight Methods is] Péng, Lǚ, Jǐ, Àn, Cǎi, Liè, Zhǒu and Kào, you all know that. [The method] Zhǒu [now] means elbow strike.”

Master Chen explains the logical flaw in defining Zhǒu as a simple elbow strike:

“Originally there was no elbow strikes [as one of the Eight Methods.] You think about it. [The Methods of] Péng, Lǚ, Jǐ, Àn, Cǎi and Liè, all those are called Taiji concepts. They are types of actions or they are principled methods of movements. Then all of a sudden, [people added a method of] Zhǒu [which is then defined as an] elbow strike. [But why an] Elbow strike? The elbow is a [specific] body part. The rest [of the Eight Methods], there is no body part [in their names].” This inconsistency strongly suggests a historical misinterpretation.

Master Chen then reveals the critical insight Master Hong received directly from his teacher, Master Chen Făkè, which resolves the inconsistency. This insight rests on a specific local dialect:

“The reason is because in the local Henan dialect, east of Henan, west of Shandong province. In that area, the [present word for] elbow, Zhǒu, is actually originally [another Chinese character that sounded similar.] [However, in that local dialect,] Zhǒu means to twist (扭). [What we now accepted ideas is based on] a mispronounced sound. The people just didn’t understand [this historical mistake].”

Although this remains a minority viewpoint, the thesis that Zhǒu originally meant “to twist” is supported by compelling evidence from multiple perspectives:

|

|

This key understanding allowed Master Hong to create a logical and consistent explanation for the Eight Methods in his Practical Methods, where all eight terms are unified as principled methods of movement rather than an inconsistent mix of concepts and body parts. This key is also central to the teachings of Master Chen.

Master Chen’s demonstration of Zhǒu (肘), the ‘Elbow technique’, begins by establishing vital structural anchor points on the student’s left arm, illustrating its true function as a method of control, not merely a strike.

To secure the student’s structure, Master Chen takes an underhand grip on the back portion of the student’s left arm (brachium). Simultaneously, he uses an overhand grip to hold the student’s left wrist.

These two grips establish the anchors: one at the back of the arm and the other at the front part of the wrist. The fulcrum or central point around which the technique will pivot is the student’s left elbow. These established anchors and the center are fundamental to the effective execution of Zhǒu.

| The two vital contact points (anchors) are highlighted by the red and green dots, respectively, in the first panel of Figure 06, marking the initial, poised position. A solid yellow line represents the rotational centerline established between the student’s elbow and Master Chen’s grip. |

|

Master Chen introduces the technique: “Zhǒu is [the result of] two of them [anchors.].” He identifies the two anchors and continues: “You see here [I have secure the two anchors.] I put a middle here [at the elbow and rotate around this middle].” This initial action establishes the primary function of this Zhǒu application: to seize and control the student’s existing structural integrity.

Master Chen initiates the technique with a controlled horizontal rotation around the centerline by pulling on the back-arm anchor and pushing on the wrist anchor. This opposing force movement is clearly shown by the red and green arrows in the first panel of Figure 06.

The result is a counter-clockwise rotation of the student’s left arm, which creates significant torque across the elbow joint, propagating into the left shoulder. Eventually, the student is forced to stumble forward to alleviate the intense pressure and structural compromise. This controlled, disruptive result is depicted in the second panel of Figure 06.

Master Chen then progresses to a deeper application, shifting the rotational center: “[I can pick any point as a center.] … [Now,] The middle is here [on my own body’s centerline. Then] I rotate both side [around this new centerline].”

He completes the demonstration by utilizing the power of the whole-body—the jin—generated by twisting the waist (the kua or dantian area). This deep torso rotation transmits overwhelming force through the established arm anchors. As a result, the student completely loses balance and falls to the ground. This final, decisive result is shown in the final panel of Figure 04. A new centerline, now based on Master Chen’s body, is added, as well as a red arrow showing the twisting of the waist.

|

Master Chen reiterates his main point, clarifying the advanced nature of this principle: “Zhǒu is not an elbow strike.” Instead, it is a sophisticated method of structural control.

This discussion of Zhǒu (肘) transcends mere semantics; it represents a fundamental distinction within Taijiquan between the internal principle of Jìn (勁, developed power or skillful force) and its external manifestation, Xíng (形, form or expression). For Master Hong and his lineage, the Practical Method system,”Zhǒu as a Twist” embodies the foundational Jìn. This Jìn is specifically the Niǔ Jìn (扭勁, twisting force/spiral energy)—the engine of the technique. Conversely, “Zhǒu as an Elbow Strike” is simply one of its potential Xíng, or ways the force can be delivered. To grasp this dynamic: |

|

|

This perspective ensures the practitioner focuses on developing correct internal structure and power before relying on crude external movements.

8. Kào (靠)

Kào (靠), for many Tai Chi practitioners, is simply understood as a shoulder strike—a powerful body check using the shoulder or torso to drive into an opponent. While this interpretation is partially correct, Master Hong’s perspective, especially within the Practical Method lineage, elevates Kào from a single technique to a profound expression of whole-body power (整勁, zhěng jìn).

Master Hong explains that Kào does not merely represent a localized strike; rather, it embodies the maximum expression of consolidated energy (勁, jìn) delivered through the largest possible body surface. This requires perfect structural alignment and the complete integration of leg power, waist torque, and a sudden release of stored energy.

As Master Hong himself eloquently stated:

|

“Kào is used within a distance of seven feet, using the body as a weapon… the whole body acts as one unit, striking with consolidated Jin, like a great mountain crashing into a wall, its force is irresistible.”

(“靠劲是七尺之内,以身体为武器,……周身一家,合劲撞击,如巨山撞壁,势不可挡。”) |

This powerful analogy—a great mountain crashing into a wall—instantly clarifies the sheer, unyielding nature of the force. It’s not a push or a bump; it’s a structural collapse directed at the opponent’s foundation.

Master Hong’s definition reframes Kào as the closest-range weapon in the Taiji arsenal, reserved for distances where hand techniques of Péng(掤), Lǔ(捋), Jǐ(擠), Àn(按) or even elbows (肘 Zhǒu) are ineffective. It represents the culmination of the four diagonal energies (四隅勁 sì yú jìn) and manifests through various body parts:

|

The essential principles derived from this whole-body application are:

|

In Master Hong’s Practical Method, Kào is the embodiment of using the entire physical structure as a single, consolidated unit of power, making it a powerful and sophisticated application of Taiji Jin.

Kào Mini-Lesson

Master Chen offers a detailed and metaphorical explanation of Kào (靠) defining it not merely as a strike, but as a dynamic expression of Yin-Yang separation through absolute structural integrity.

|

Master Chen begins by clarifying the fundamental nature of the interaction: “When you split yin and yang like a ball moving against the floor, that’s Kào.”

In this powerful analogy, the Ball is Yin and the Floor is Yang. The “separation” is not physical distance, but the dynamic relationship created at the point of contact. From the ball’s own frame of reference, it remains perfectly still; the perception of motion is the floor shifting beneath it. The ball’s path is defined by the floor’s unyielding resistance (Yang) and its own circular motion (Yin). This illustrates that the force in Kào is derived from the ground and expressed through an integrated body structure, not through individual effort or reaching. |

|

Master Chen elaborated on this stillness by demonstrating the technique against a wall (or a fixed benchmark). He stressed that any attempt to push or reach with a singular body part would constitute movement and therefore be an error: “So Kào, the last one [of the Eight Methods], is a yin-yang [separation] here [based on whole body movement.] So if you look at this here [I position myself against this wall and you use this wall] as a benchmark. My body is [initially] here but my body does not go through anything [meaning I am not trying to hit the wall.] Okay? [If any part of my body tries to interact with the wall,] it means this [type of interaction] is [considered to be] movement [which is an error.] [The technique of Kào no movement but only in relation to that [benchmark wall.] Can you see?”

|

This initial alignment (shown in the right panel of Figure 07 with anchor lines) emphasizes the zero-movement setup. The practitioner then executes Kào by quickly shifting the whole body structure (moving quickly to the right in the demonstration):”It’s here [Kào.] So there’s a yin-yang split there in regard to the floor and that’s called Kào. No body movement. Kào is a whole body movement.” |

The final position (left panel of Figure 07) illustrates the shift: the red arrows represent the complete, unified movement of the body, which is the Yin-Yang separation of the technique—the body moves with respect to the floor, not toward the target.

| To finalize the concept of whole-body action (整勁, zhěng jìn), Master Chen used the powerful analogy of a car collision: “Whole body movement is same as a car hitting you. The car never moves. It only moves in relation to the floor. The car goes forward. [Each] car [part] itself does not do this [hit you individually, one at a time.] [Collision hits you,] it’s one piece.” |

|

|

The Car represents the body executing Kào. The key takeaway is that the force arrives not as a sequence of individual pushes (fenders, hood, engine), but as a single, unified, and devastating mass. From the car’s perspective, it remains structurally sound and stationary; its motion and its impact are only defined in relation to the ground beneath it.

This reinforces the principle of Kào: The body maintains its structural integrity and ground connection while the interaction occurs, transferring force not through localized striking, but through the unyielding, unified mass of the entire structure. |

Master Chen’s demonstration provides a practical roadmap for executing Kào (靠), emphasizing that this whole-body strike is defined not by the specific point of contact, but by the unified momentum driving the force.

Master Chen immediately broadens the definition of Kào, moving it beyond the common understanding of a shoulder strike: “Kào is a whole body strike but you can use any part [of your body] to do the strike [not just the shoulder].”

|

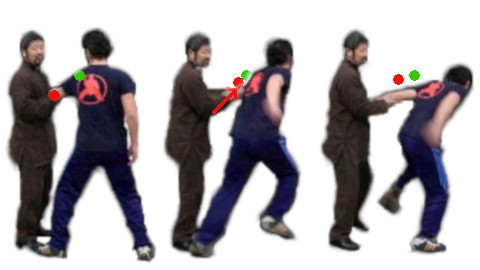

Master Chen begins a demonstration by establishing a crucial close-range control—holding the back of the student’s neck and forearm to maintain proximity (as seen in the left panel of Figure 08).

He then illustrates the versatility of the contact point: “So [body part that does the striking,] it can be here [on the front thigh], can you see here?” |

|

The execution of Kào involves a swift, unified movement of Master Chen’s entire body toward the student (middle panel of Figure 08). The movement is not a push from the thigh, but a structure-driven shift. The action concludes when the student’s foundation is successfully penetrated and uprooted: “So when I hit, the whole body is like this.” The final position (right panel of Figure 08) shows the student unbalanced, confirming the effectiveness of the whole-body momentum.

|

Master Chen reinforces the concept of whole-body weaponization in a second example (Figure 09), starting with his right shoulder in direct contact with the student’s chest, controlling the student’s arms to lock the range.

He reiterates: “[The initial point of contact,] it can be anywhere, right? … It [the weapon for the initial strike,] can be anywhere.” The critical warning follows: “But when you hit, the whole body has to move. Otherwise, it’s like this [a movement of just one body part].” |

Master Chen demonstrates a series of ineffective, localized strikes—isolated moves with the shoulder, chest, and leg—explaining: “This [hit with isolated movement] is light. This is just hitting. That’s all hitting.”

The true essence of Kào requires connection before culmination: “[The technique of Kào requires you] to the touch [then] use another [body] part [to power the action]. So once you touch, you use the whole body to slam on it [the target].”

This whole-body slam is vividly shown in the middle panel of Figure 08, where the student is visibly knocked off balance by the penetrating uprooting force. This technique demands correct structural alignment to transmit grounded force without energy loss. The final action (right panel of Figure 08) involves a sharp twist of the waist, completing the technique by directing the entire torso as the striking surface, powered by the legs.

Master Chen elaborates on the deep difficulty of mastering Kào by introducing a profound psychological paradox regarding the feeling of its execution:”The feeling or the action is that when I touch you [my opponent], it has to be like him [some other person] picking me up and throwing me on you. So the power is like that.”

This is the key to Kào: the power feels external because the practitioner is simply directing the integrated, grounded momentum, rather than consciously generating force with local muscle groups.

|

He clarifies why this is difficult: “If I do it [the act of throwing into you] by myself [it is not Kào], so Kào is very difficult because it feels like somebody else is doing it.” Any conscious attempt to “do” the action usually makes it local and ineffective. “Do you understand that? So it [the technique] has to be that something [which] is bigger than me and [that something] did it with me to you. So that’s very, very difficult.” This “something bigger” is the unified whole-body power (整勁), rooted in the ground, directed by the mind (意, yì), and delivered instantly as a single, unyielding mass. |

|

With the analysis of this unified striking method, Master Chen concludes the lesson: “That’s the Eight Techniques. Thank you.”

In sum, a significant pitfall for many students of Taijiquan is the tendency to fixate on Zhèng Jìn (Primary Energy) and the four cardinal directions while neglecting the subtle but essential role of Yú Jìn (Diagonal Energy). To treat these two energies as distinct or sequential is, as Master Hong stresses, a fundamental misinterpretation of the art’s integrated nature.

|

Instead, the relationship between them must be understood as a coordinated whole—a dynamic, inseparable duality akin to Yin and Yang. The true essence of this coordination is beautifully captured by Master Hong’s assertion:

“Every movement in Taijiquan involves the coordination of the main (Zheng) and the diagonal (Yu). Zheng is the final direction of the attack; Yu is the subtle process of leading, neutralizing, and storing energy. Without Yu, Zheng cannot exist; without Zheng, Yu is useless.” (“太极拳的每一动作,都有正隅的配合。正是攻击的最终方向,隅是引化、蓄劲的细微过程。无隅则正不存,无正则隅无用。”) |

This crucial insight underscores that mastery in Taijiquan is not about generating raw power, but about the seamless integration of neutralizing, leading, and storing energy (Yú Jìn) with the final, purposeful direction of attack (Zhèng Jìn). Embracing this holistic perspective is the key to unlocking the sophisticated power and profound effectiveness of the Practical Method.