|

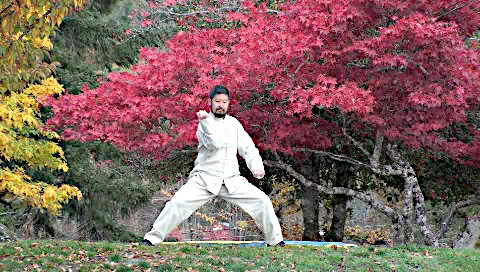

The Positive Circle, a foundational element of Chen Style Taiji, is a dynamic sequence that taps into your body’s innate potential through three essential phases: In with Elbow, Turn with Waist, and Out with Hand. These movements are further divided into two distinct halves—one emphasizing pulling, the other pushing. Though deceptively simple at first glance, they hold the key to unlocking Taiji’s profound power and subtle elegance. Mastering the Positive Circle is not merely about physical movement; it’s about discovering a deeper harmony between intention, energy, and flow. |

| Master Chen applied these principles to dissect the Yilu form, the fundamental sequence of Chen Style Tai Chi. By analyzing each movement through the lens of hand-foot connections (手脚相连) and the concept of switching, practitioners gain profound insights into the underlying mechanics and energy flow. This understanding, supported by simple mechanical models, not only refines technical skill but also fosters a deeper connection between body and mind. | |

| (This is an edited transcript of the Hand-Foot Connections filmed in Oct, 2010, Edmonton, Canada.) |

|

|

Master Chen begins. “In both the Yi Lu form and Cannon Fist, even in push hands, each person typically has one dominant side. The form is designed with right-handed movement in mind. Most of the time, the focus is on the right hand and and you’re looking that way. When you turn, that’s still the focus. The left hand is primarily in the system as a support. It helps catch and assist that kind of action.”

|

He continues. “When we talk about coordination, the dominant pair is always the right hand and the rear foot. The right hand is consistently the central point of focus, its dominance is almost a given. While the rear foot is generally the dominant one, that role can shift to the front foot depending on the movement.”

1. First Half of the Positive Circle

|

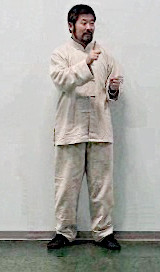

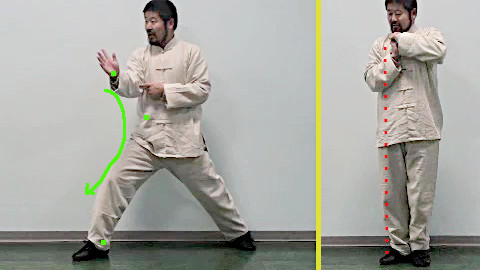

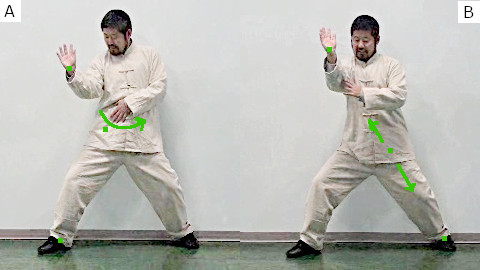

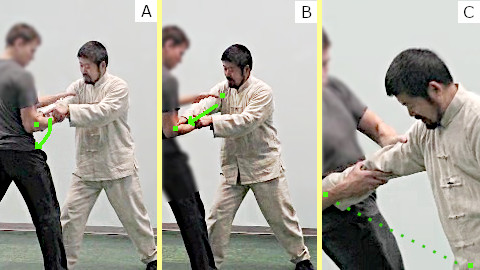

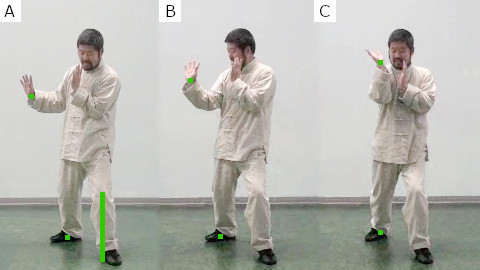

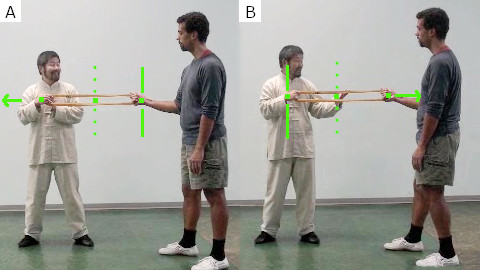

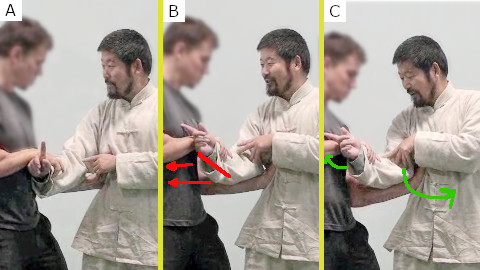

Master Chen stands in the starting position of the Positive Circle, as shown in Figure 01A. He begins his explanation: “I’ll use this posture, the neutral posture, to illustrate the hand-foot connection within the fundamental [Positive] Circle. In this circle, the first move [‘In with Elbow’] begins with your hand in the starting posture, as the elbow [is] pulling the hand back.” To emphasize that only the elbow is moving, Master Chen uses his free left hand to pull the right elbow back. |

He describes his initial ready structure as follows: “In this movement, there are three key elements—one end is your hand, the other end is your front foot, and the center is your front kua. The center should form a line, though you operate from a dot [on the kua]. You’re using the dot here, supported by a [vertical] line [that passes from the front shoulder through the front kua]. The dot remains stationary.” These elements are illustrated in Figure 01A as green dots, with the vertical line represented by a green dashed line.

Master Chen then demonstrates the first half of the Positive Circle. Starting from the ready position, he transitions into ‘In with Elbow’ followed by ‘Turn with Waist’. He explains the motion: “Your hand starts [at the ready position], while the shoulder and elbow draw inward toward [the dantian]. Through this action, power shifts to the front heel, creating the interaction [the turning of the waist]. As you execute [Turn with waist], you’re actively engaging the connection between the front finger and the front foot.” Figure 01B shows the final position of the first half of the Positive Circle

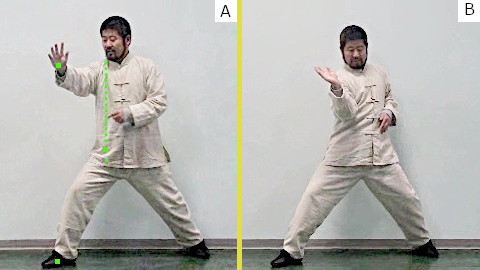

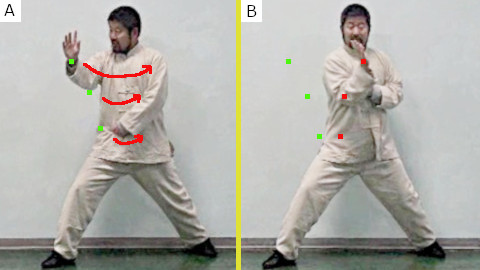

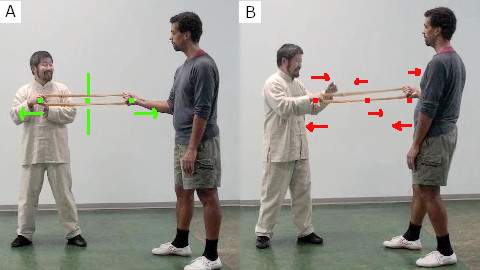

| Master Chen introduces a Rubber Band model to illustrate how the action of “Turn with Waist” arises from the interaction between the front finger and front foot. In Figure 02A, which represents the model’s initial state, he instructs two students to each hold one end of a rubber band and stretch it taut, forming a base that connects the endpoints. He explains: “In this configuration [of a stretched rubber band], this [end] would be the front heel [indicating the lower end of the band]. |

|

This [upper end of the band] is the front hand, and this [holding the middle of the band] is the front kua. [I mark a halfway point on the band between the kua and the hand to represent the elbow.] If I lock this [kua, the middle of the band] in place, and you [my students also] lock your hands [representing the position of the foot and hand respectively] in place, [In the first move, ‘In with Elbow,’] the elbow here, which this marker shows [as halfway between the hand and the kua], comes toward the dantian area, causing this to happen.”

Master Chen tugs at the band, as shown in Figure 02A with a green arrow, pulling it away from its original vertical alignment. The band now forms an open triangle, depicted in Figure 02B, with the base of the triangle represented by a green dashed line. He continues: “[The lower end of the band representing the foot] is anchored to the floor, and there is no possibility of it moving. This one [the upper end of the band representing the hand] is suspended in the air. When I power up [by adding the second movement ‘Turn with Waist’], you will see that this [the top, hand] starts to move.”

Master Chen then pulls the middle of the band with great force, causing the top end to shift from its original position. This is illustrated in Figure 2C, where a green line highlights the new position of the hand as it moves away from its initial location. He explains: “And this [movement of the hand resulting from my strong pull] is what we call the front hand coming back.”

|

He then contrasts the Taiji action, as illustrated by the rubber band models, with common movement patterns shown in Figure 3. He tells his students: “[Common movement,] It’s very, very different, or we can say it’s fundamentally different from this [Taiji] action.”

In Figure 03A, he instructs his student: “Okay, you hold it [the top end of the band].” This creates the initial position of the demonstration, with the rubber band stretched taut between two points. |

Master Chen then explains that in a typical movement: “I’ll move you, you’ll see. Without the pivoting point—the front kua or the waist dantian area—this is how most people do Taiji.” Figure 03B illustrates this alternate action, where movement is generated by Master Chen holding and moving the top end of the band, which represents the hand. Compared to the previous model, this version lacks a triangular structure, as the action involves only two points.

Master Chen elaborates: “You can see that this action [moving the hand] neither produces nor reduces anything. It’s basically non-moving, a useless waste of your time.”

He emphasizes how the rubber band model accurately represents the correct movement in the first half of the positive circle: “What we want to do is, number one, anchor [the foot]; this is called double fix [double lock]. The foot doesn’t move at all. It stays motionless, both on and off the track. This one [the hand] is fixed in a direction [single lock]. It can [only] move along that direction [of the track]. It’s as if the hand is tethered to a track, free to travel but unable to stray. It [the hand] moves [on the track] because this [the Dantian] does that [pulling the band and dragging it along the track] to it. So the more you refuse to move [the hand], the more power we generate.”

| Master Chen begins in the ready stance as shown in Figure 04A, stating: “Okay, that’s the [rubber band model of Taiji] action. Now watch how I perform it. See if you can observe the similarity or connection [to the rubber band model], how that analogy applies to the body. The starting position is already bent into an arch.” The green line highlights the arch formed by the connection between the hand, kua, and front foot. |

|

He contrasts this stance with a straight posture shown in Figure 04B: “I’m not standing here [in a straight line]. So [in the ready position], here [the elbow], here [the kua], here [the foot]—it’s not a straight line.” This contrast is illustrated by a red line that connects the front hand, kua, and front foot.

|

Returning to the initial position, Master Chen explains: “I’m already here. This point here [the elbow], here [the kua], here [the foot]—these three points pull backward. We do not allow tossing [meaning individual sideways movement of those points]. [The correct action is] it [the waist] turns backward, causing the hand to retract. That’s what’s happening. If the power [from the kua] doesn’t return 100% to the heel, you’re tossing again. |

So nothing moves [meaning there is only rotational action]. This [the turning of the waist] forces power into the heel.” In Figure 05, Master Chen demonstrates this incorrect movement of tossing with red lines highlighting the error of moving hand, elbow and the kua.

Master Chen tries to outline a guideline for the proportion of power generated during this action: “So the power generated is that…” He pauses, adding a caution: “By the way, [if] you’re a mathematician, [you’ll find that] the numbers don’t [really] jive. We’re just using numbers to illustrate an idea. It’s not like 1 plus 1 equals 2.”

Back in ready stance, he continues: “It means you have an X amount of force [in the ready stance] that’s available to use [for this action]. Let’s say that [amount of available force is] 100. [A correct movement requires that] all 100 [of this force] must go to the heel. Then somehow, by doing that [putting all available force into the heel], there’s a residual [component] that pulls this point here [the fingertip]. When you finish [the Taiji action], the [total force for the system that was once] 100 becomes 130.

So it’s not like 150 is here [in the foot], 50 is here [at the fingertip], and 0 is here [at the kua]; nor is it 30 [at the foot], 30 [at the kua], and 30 [at the hand]. [The correct action requires] you to imagine all of it [available force] went there [into the foot]. Not only that [during the action of ‘Turn with Waist’], you feel as though you’ve added [more] power to it [the foot]—maybe it’s [now] 130 there [in the foot], and maybe there’s 50 here [at the kua]. In the end, there’s about 60 or 70 [at the hand]. [The end result for a proper first half of the positive circle is that] the real power is more concentrated there [at the foot] and less here [at the hand]. [This imbalance is] causing an energy fluctuation.”

He concludes: “This is the first move [half of the positive circle]. This is one possible configuration, and quite common, although not very obvious in our Taiji actions—because this is a front-ended move, meaning your action is directed toward the back.”

2. Second Half of the Positive Circle

|

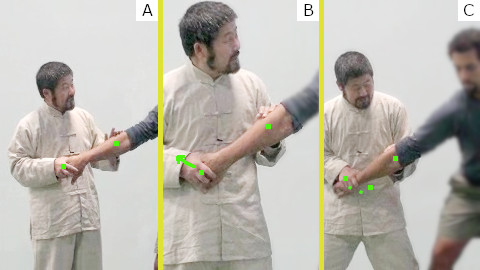

The third move, “Out with Hand,” completes the second half of the Positive Circle. In Figure 06, Master Chen begins by explaining the hand movement: “The second combination [in the Positive Circle] involves switching the hand backward [towards the starting position] in this way. When you go that direction [as mandated in the move ‘Out with Hand’], power can no longer move forward. [This half of the Positive Circle requires] you [to] use the rear kua as the center, as the lever point.” The shift in the front hand’s position is illustrated in Figure 06. |

Master Chen continues: “When you execute this [carry out the action of ‘Out with Hand’], the power splits between the rear foot and the front hand. [To explain this type of action], I cannot use this [rubber band model] here. [Instead], I’ll use a different [descriptive model] here.

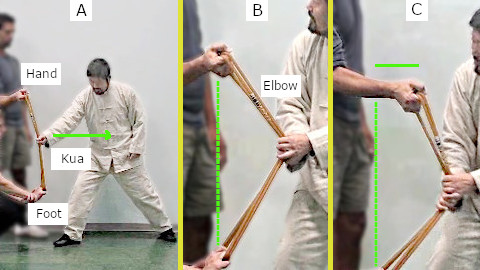

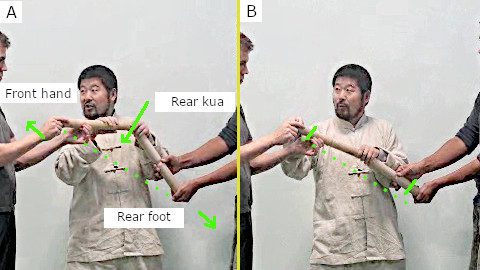

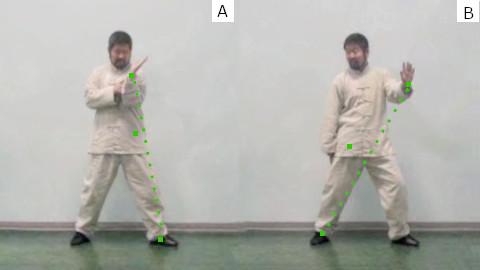

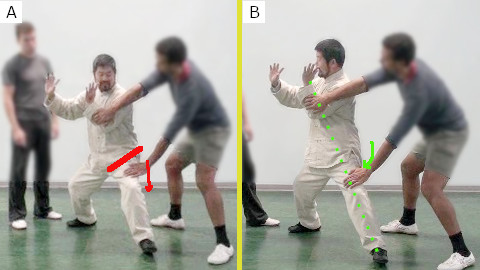

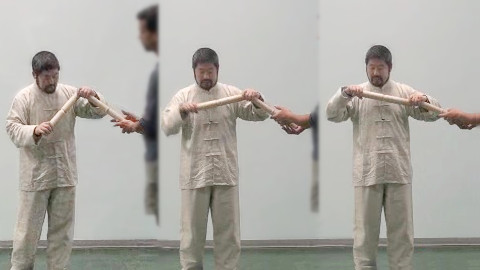

| Master Chen then introduces his stick model for the second half of the Positive Circle. This is shown in Figure 07. Master Chen begins, “Now, if I stand right here.” He positions himself between his two students. Each student holds a stick, with one end of each stick touching to form an open triangle. This structure is shown in Figure 07A with a green dash line showing the base of the open triangle. |

|

Master Chen continues. “You see, roughly this [end of the stick located on my right side] represents my front hand. [The end of the second stick on my left side,] this corresponds to my rear foot. [The sticks are not as long as my arms and legs] so this [stick model] serves as a smaller version [of the structure of my body]. [In this model, all the parts of the body between my front hand such as] my shoulder and this part here [the chest], and the kua [is] all located in this area here [between the two sticks]. The kua represents the apex of the triangle where the two sticks meet, with the elbow positioned somewhere in the middle of the right stick [between the hand and the kua].” Those landmarks are labelled in Figure 07A.

“So [when the hand is] on the way out, it’s roughly [described as by this stick model as] this way here.” Master Chen points to the student holding the left stick. He describes this left side as follows: “[On this end, representing the rear foot.] This [action at the rear foot] is called double lock. It’s locked this way [in the x-axis], and locked this way [in the y-axis]. [The rear foot] It’s like nailed down.”

Master Chen then points to the student holding the right stick and describes this section: “This [right side represent the front hand] is put on the track. [The front hand can only move on this track.]”

After setting up the basic premise of this stick model, Master Chen begins to explain the actions within the model. He points to the middle of the model where the two sticks connect, forming the apex of the open triangle. Pointing to this apex, he says, “There is an arch here [since the two sticks are connected at an angle forming a triangle]. I push this here [apex of the triangle] down [towards the open base of the triangle]. That push causes this one [the right side representing the front hand] to go forward.” In Figure 07A, a green arrow shows the push on the apex of the triangle. As a result, the two ends moves away from the middle as shown by two green arrows.

Master Chen emphasizes this result by using an external reference point, showing the extension of the stick on the right side from the reference point as a direct result of the movement at the triangle’s apex. This result is shown in Figure 07B. He explains the importance of this stick model, “This [movement of the stick model] is [the Positive Circle action of] ‘Out with Hand’. The [action of] hand out, we say you lead with the hand, because if you don’t lead with the hand, this [movement of the hand] will derail. [In a correct Taiji action,] either you lead with the hand [the end of the right stick], or you lead with your elbow here [represented as a point in the middle of the right stick]. The power must be a split from the center [the apex of the triangle]. It must borrow through the split. Power comes out because the rear part does not move. In this scenario [the second part of the Positive Circle, the rear does not move. In contrast,] the other scenario [the first part of the Positive Circle as described previously] is the opposite, that the front does not move.”

After describing the stick model, Master Chen relates it to the actual movement in the second half of the Positive Circle. Master Chen explains, “I will show you again physically. We are here already [after the movement of ‘Turn with Waist’]. Assuming that what we did is double-edged, meaning the shoulders are like this [a triangle with an apex pointing up],

|

and also my elbow and the dantian are here [as a triangle with an apex pointing down]. So there are two sets [of triangles in this action of ‘Out with hand’]. One going this way [by the apex of the triangle being pushed down], one going this way [by the apex of the triangle being pushed up], [the combine result is the front hand and rear foot pushing away from each other].” Figure 8A and Figure 8B shows the orientation of the two triangles. |

“So on the second one [the second half of the Positive Circle] here, it’s the interaction of the hand with the rear foot. So if you only look at my [front] shoulders here, [In this structure,] there is a [virtual 45 degree] line here [that connects the front hand and the rear foot]. The [front] shoulders will go towards this [45 degree] line. This move [of the shoulder] here pushes the front hand out [away from the body]. The rear foot is locked. Your power must be pushed all the way into the rear foot for the power to release out [through the hand].” In Figure 08C, a green dashed line traces a 45-degree angle, linking the front hand to the rear foot. Two green triangles, each accompanied by a bold green arrow, highlight the motion of their apexes, both pointing inward toward the diagonal line, emphasizing convergence towards the diagonal.

Master Chen then instructs one of his students to hold hold his rear ankle with both hands, explaining, “Now if you sit down here and grab my ankle [with] two hands, to get a larger area… I’m going to do what is called the wrong way. I just did this.” Master Chen shifts his weight away from the rear ankle. This is considered to be a wrong move.

He then instructs another student to hold his front wrist. He says, “… hold me, … allow movement [of the arm], but you can move with me to feel.” Master Chen performs a series of normal movements with the front hand and describes, “See this, can you feel I did it [the movement of the front hand]?”

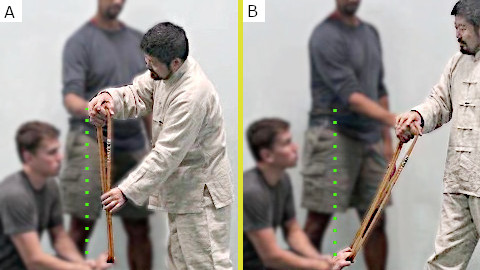

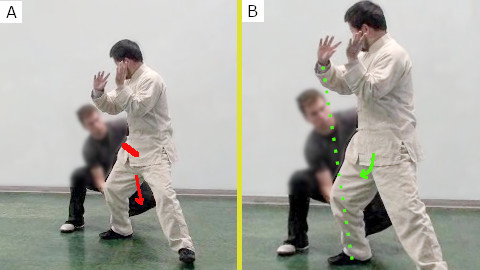

| Master Chen then demonstrates the correct Taiji movement as illustrated in Figure 09, beginning with the action “Out with Hand” shown in Figure 09A. He explains, “I lock everything onto this track [the virtual 45 degree line], and push the excessive parts [of the body such as the front shoulder and the rear chest] into this line. And all the way until, can you feel it pushed in there [into the rear foot]? When it [all the power] is there, it [the power] comes back [towards the front of the body]. |

|

When this happens, the front [hand] has what we call amplified power.” The 45 degree line is represented by a green dashed line in Figure 09A. The final posture is shown in Figure 09B. Both students confirm Master Chen’s description.

Master Chen elaborates on this result: “[The front hand,] this is the only opening. Every part is moving into this tube with the foot being the strongest, most condensed area. [In the beginning, the power,] Everything goes to the ankle, onto the heel, [but the rear foot is double lock so] nothing moves. [As a result,] Everything shoots back out [through the hand].”

Master Chen concludes: “So in Tai Chi movements, when we talk about the hand-foot combination, there are only these two scenarios [as represented by the two halves of the Positive Circle]. And that’s why in a way, in push hands, you might feel that I’m very flexible, the movements are unpredictable, but in training and in reality, there are only [those] two scenarios.”

He explains his conclusion using a computer analogy: “Like everything else in the computer system, it’s only 010101. Although you can generate all sorts of things out of them, the basic fundamental principle is 010101.”

3. Switching

|

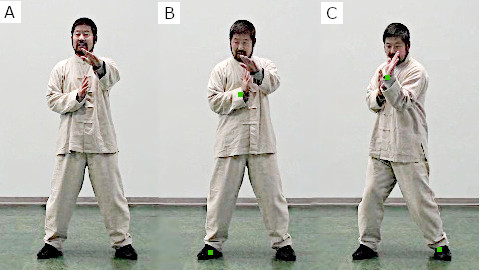

Master Chen emphasizes that “all action proceeds this way from here [the first half of the Positive Circle, including the action ‘In with Elbow’ and ‘Turn with Waist’],” as illustrated in Figure 10A. He continues, “Or this way from here [the second half of the Positive Circle, including the action ‘Out with Hand’],” as shown in Figure 10B. Introducing a new concept, Master Chen describes the role of the Dantian, stating, “But in both cases [scenarios], focus here [the center of the body]. It is the extension from here [at the Kua (胯)].” |

Expanding on this idea, Master Chen explains: “The method of generating power [in the first half of the Positive Circle] involves twisting [of the waist] to cause this [the front kua] to extend. Then, during the outward movement [the second half of the Positive Circle], it is this area [the rear kua] that extends.” These movements are represented in Figure 10 by green arrows.

| Master Chen then contrasts this action with a typical movement, stating, “So it’s not wobbling like that.” He concludes, “These are the two actions that we use to create the hand-foot combination.” Figure 11 illustrates an example of improper tossing, with red lines and dots indicating the incorrect positioning of various body parts. |

|

|

Master Chen continues, “I switch to this [left] side,” offering a different perspective while emphasizing that the same principles still apply. Figure 12 illustrates the Positive Circle beginning with the left hand. He reiterates the concept: “There are only two possibilities. [The first scenario ending with the action of ‘In with Elbow’] is when I [with the motion of the elbow] come back [towards my body], power is on the front foot.” |

This is depicted in Figure 12A, where the green dashed line highlights the connection between the front hand and front foot. The green dots emphasize the significance of the front hand, front kua, and front foot.

Master Chen continues, “[the second scenario is the action of ‘Out with Hand’] When I [with my front hand] go out, power is on the rear foot.” Figure 12B illustrates this with a green dashed line showing the connection between the front hand and rear leg. The green dots indicate the importance of the front hand, rear kua, and rear leg.

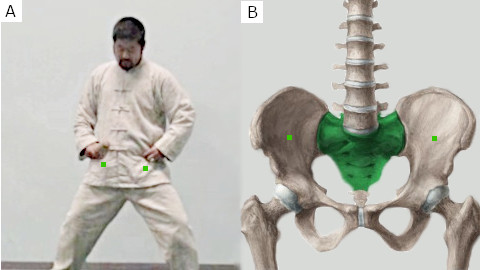

He then elaborates on the concept of switching: “The switching is in the dantian area, but more specifically, it is on the kua. The two kuas are in different positions. This is actually called switching. Meaning, when I’m doing this here [the first half of the Positive Circle], the power rests here [in the front kua]. When I’m doing this [the second half of the Positive Circle], it [the power] does not rest here [in the front kua]. It rests here [in the rear kua], although it [the two kua] is linked as one piece [anatomically by the pelvis more specifically the pubic region and sacrum]. So this is called a switching. Meaning, it does not move, and yet it changes position.”

| Master Chen then introduces a mechanical model to illustrate the concept of switching. “Let me use this example to show you what I mean by switching.” He instructs his student to hold a short stick, explaining, “This [the end of the stick where you are holding] is a round ball, there’s gear here [as represented by this short stick]. So you grab it [one end of the stick] like this.” Master Chen then grasps the opposite end of the stick, as shown in Figure 13A. |

|

He continues, “My stick also has grooves on it [that connects with your gear]. And when you do this [holding onto your end of the stick], [this means the] two gears lock. When I turn [the stick at my end], you [on your end] have to turn with it.” The green arrows in Figure 13A illustrate that when Master Chen rotates his end of the stick, the student’s end also rotates.

The key aspect of this mechanical model, as Master Chen explains, is: “[My end of the stick can turn your end means] I don’t have to be local. I don’t have to be here [at your end] with you [to turn you]. I can have any extension [or length of the stick]. I can turn in here [on my end of the stick]. That [turn] is exactly the same as here [on the other side of the stick].” Figure 13B shows this with an extended green line, demonstrating that even with increased distance between the two ends of the stick, the same turning connection remains intact.

|

Master Chen applies this physical model to the movement of the Positive Circle. Standing in a ready stance, as shown in Figure 14A, green dots highlight the importance of the kua. He explains, “In this case [of the action of the kua using the Positive Circle] here, I engage you here [on the front kua], but I can do it through here [the rear kua]. Because it [both kua] is [connected as] one piece [as the pelvis]. If I move [pelvis] as one piece, [when there is movement in the rear] you can feel it here [in the front kua]. |

So this type of action is called switching. So I’m just adding that to this topic here. And eventually, I will have a specific one on switching.” Figure 14B presents an anatomical model of the pelvis to emphasize that the pelvis functions as a single unit.

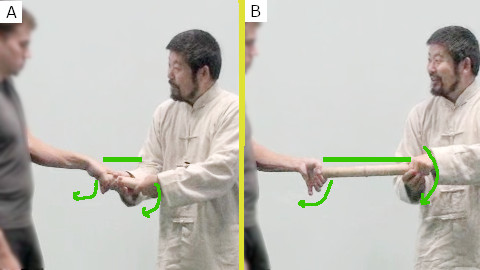

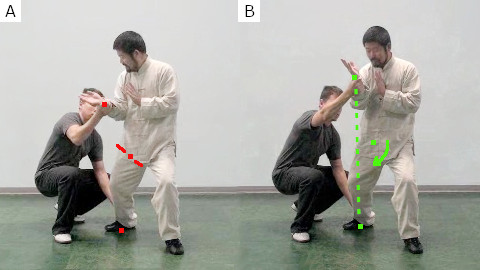

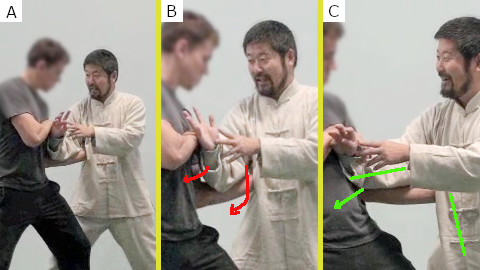

| Master Chen applies this concept to a practical application. He explains, “Since we’re on the topic [of switching], I like to just show you this move.” He instructs his student, “You grab [my arm with both hands].” This action is illustrated in Figure 15A. He then describes the application: “If I want to do this [push towards the student’s body with a slight twist of the arm], can you feel here?”The push elicits a response from the student, as seen in Figure 15A. “Job done, but not enough. |

|

So I caught you [by twisting my arm], but not much power is generated out of here [this twist]. You can see how it moves. So because of this action, I caught you, but there is not much power. Okay?”

Master Chen then applies the concept of switching by shifting the source of rotation from the arm to his shoulder. This is shown in Figure 15B, with a green arrow indicating the source of power at the front shoulder. He explains, “So I will do the same [action], but the power will come out of here [the shoulder]. Now can you see? And eventually, I can switch [the source of power to different joints of the body].”

He highlights a key requirement in the process: “This [leading hand on opponent] is the lock.” Once this is established, Master Chen explains that the process can continue: “I can switch [the source of power] to the kua, and then [eventually] switch to my foot. Can you see when it’s on the foot? The power is amplified. So this is the method.” The final result is the student being unbalanced by Master Chen’s actions, as shown in Figure 15C. The green dotted line illustrates that the source of power originates from the rear foot.

|

Master Chen explores the concept of switching through another example. He grabs a student’s wrist with his rear hand and places his front hand on the student’s elbow, performing an arm bar. The initial position for this application is shown in Figure 16A. He explains, “The power [on the student] is from here [his wrist] to here [his elbow].”

Master Chen then applies the arm bar and asks, “See? Can you feel that? So the action is correct, but not much came out.” |

He proceeds to demonstrate the concept of switching. He first describes the initial step: “When I do this [slight twist of the opponent’s wrist] here, can you see I found a lock? It [the hold on the wrist] doesn’t move anymore.” This result is illustrated in Figure 16B, with the green arrow indicating the presence of the wrist lock.

He then describes the progressive steps of switching that generate increasing power: “Then I move from here [the front kua]. Can you see it’s bigger? It’s bigger. And then I move [from] here [stomach] to here [rear foot]. Okay? It [size of movement is] even bigger. Meaning, when I make a larger, longer move, you can feel it more readily [on your arm]. See [when the action is from my rear foot], look, it [the opponent’s reaction] is right there. Otherwise when it [range of movement] is smaller, it [the opponent’s reaction] is actually longer. [Meaning,] It takes longer to achieve it [an action that disturbs your opponent].”

The final result of switching the source of power to the rear foot is shown in Figure 16C, with the dotted green line indicating the maintenance of the wrist lock while the power originates from the rear foot. Master Chen reminds his students that this is a scenario where the lock (anchor) is close to the point of contact. He suggests alternative cases where the hand is not locked but the rear foot serves as the anchor. In such cases, “Very small move, you can feel it right away because I switched to a bigger one. That’s a different concept.”

Master Chen concludes, “Now, the hand-foot combination (手脚相连) here, that’s the basic principle.”

4. Application to ‘Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar’

Master Chen begins, “I’m going to go through all the movements, the actions, in Yilu—not necessarily following the choreography—but we’ll work on them in a stationary manner to demonstrate how, in every move, [how] the [hand-foot] combination works.” Using the first move, Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar (金刚捣碓; Jingang Daodui), Master Chen offers a detailed breakdown of the actions in relation to the theory of hand-foot combination. This series of movements is divided into discrete sections.

Starting position

|

[Starting in parallel stance. The feet is shoulder and a half width apart. Right hand on the centerline close to the body. Left hand out at shoulder level.] This initial position is illustrated in Figure 17A. |

1. Right hand

Master Chen explains, “First move here. There is this [right rear] hand here, moves with this [right] foot, because the direction is this turn [towards the left]. This [front left] hand here, [does] no move yet. It [front left hand] is complementary here.” Master Chen demonstrates the stretch between the right hand and the right foot by raising the right hand as the body torques left. The term “torques left” is used instead of “turn left” to emphasize the creation of stretch between the right hand and right foot. This is shown in Figure 17B.

2. Left hand

Master Chen continues, “Next move here [concerns with the left hand]. [The stretch] is this [front left hand] edge here, with this [left] foot.” This posture is shown in Figure 17C. Master Chen demonstrates a slight turn to the right to increase the stretch between the left hand and left foot. It is important to note that this left-side stretch should not interfere with the stretch between the right hand and right heel.

Master Chen reminds us, “So [the movement is] one, two. So if I dissect, and take them apart, it’s one [right hand] on this [right] heel, two [left front hand] on this [left] heel.”

3. Turn to the right

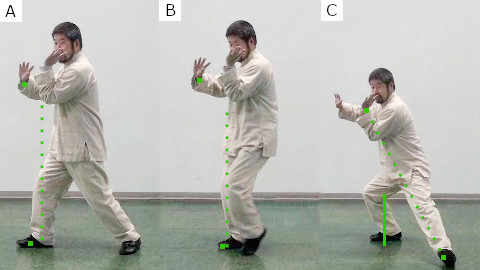

|

Master Chen continues by turning the body toward the right, pulling the left foot into the centerline, and then stepping out at a 45-degree angle with the left foot. The initial movement of turning the body to the right is shown in Figure 18A. This turn represents a switch in the center of mass from the middle of the body to the right side. It is important to note the use of the term “switch” rather than “shift,” as a shift implies a conventional movement that can lead to the error of tossing. The term “switch” refers to a Taiji movement in which the change in center of mass results from the turn itself. |

As Master Chen narrates his movement: “This [right] foot actually is the anchor, like the rod.” This rod is illustrated as a green dashed line in Figure 18A. He continues, “The real power is split from the left heel to the front [left] hand, here. As soon as this happens, you lift [your left leg and move it into the centerline], but the intention is still from the [left] fingertip to my [left] heel.” This action is depicted in Figure 17B, where the left leg is positioned beside the right rear anchor.

Master Chen elaborates further: “That’s why [after left leg is brought in], this [right side] is too short, then [the next action is] the [left] heel will extend [45 degrees forward].” This position is shown in Figure 17C, with the solid green line representing the right-side anchor. He continues, “When I do this here [extend my left heel forward], power is from this heel, extending all the way here [front left hand].” The dotted green line in Figure 18C illustrates the connection between the front left hand and the front left heel.

4. Left foot land, turn left with right hand.

|

Master Chen continues. “The next move here, you land [with your left foot.] This [front left foot] becomes an anchor. Okay? This is an anchor rod.” This is shown in Figure 19A with the green line indicating the anchor and the green dots highlights the importance of the hand-foot connection. |

5. Step forward with right foot and right hand.

|

[The left foot serves as a stable anchor. The right hand and right foot move in coordination, drawing the right side inward toward the left. This motion continues until the right side aligns with the body’s center line, directly in front.] |

6. Right Knees up. Drop right fist in left palm. Step back into parallel stance.

|

[The left foot remains the anchor throughout the movement. Use the right hand to lift the right foot, causing the right knee to rise. This upward motion of the right hand resembles the gesture in Out with Hand, except the trajectory is vertical rather than angled at 45 degrees.

Raise the right hand to eye level and the right knee to hip level before allowing both to descend. As the right hand lowers, it gradually forms a fist. The right foot lands parallel to the left, positioned approximately one and a half shoulder widths apart. |

The movement known as Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar concludes when the left hand covers the right fist, with both hands positioned in front of the dantian. The feet should be in a parallel stance, spaced shoulder and a half width apart. ]

5. Energy breaks

Master Chen introduces another concept during the discussion in Movement 3. He explains, “That’s why [an serious error occurs]. If anything breaks [the hand foot relationships in the posture], that [error] is what we call the energy breaking up. [The Taiji requirement is that] the energy has to be one piece.”

|

Master Chen then uses this opportunity to provide additional details on the concept of energy breaks. Figure 22 shows how he explains this concept with his student’s help. He positions his student’s hands on his body to provide feedback on the energy break in the structure. He explains, “In this move here, particularly in the combination we’re talking about, touch me here [on the front left forearm] with this hand, and touch me here [on the front left thigh with the other hand]. Feel, try to feel [the connection within structure], from here [front left finger] to my [front left] foot.” |

Master Chen performs several squatting movements to illustrate an incorrect version of the move. The error occurs because there is a bend in the front kua, as shown by a red line, and a drop in the waist as shown by a red arrow. He continues, “Can you see, can you feel, [the area] in between [the hand and foot] there’s something broken? [in the front kua]” This position is shown in Figure 22A, with red lines marking the structural errors. Master Chen adds, “Like here [on my front left kua]. Can you feel there’s nothing there? [In terms of connection between the two points.]”

Next, Master Chen demonstrates the proper Taiji alignment. He begins, “Now I’ll show you how it is — can you feel it’s connected?” The correct structure is shown in Figure 22B, where a green dotted line highlights the intention to maintain the connection between the front left hand and the front left heel, and the body adjustment that reinforces it. Another key action is tucking in the tailbone to strengthen this link, as indicated by a green arrow. Master Chen asks his student, “Can you feel every part [of this connected structure], from the heel all the way stretching to here [the hand]? And you can feel every part of it, including the parts that you don’t touch. You can feel it’s extended. There’s a stretch.”

Master Chen reminds his student that the concept of energy breaks applies to the entire body. He then describes how this idea applies to the right side. He instructs his student to place their hands on his body as he performs the action.

| He says, “On this [right rear] side here, while I’m doing that [action] here, if you touch here [the rear right calf], and here [the rear right kua], can you feel it [the right side] is broken?” This moment is shown in Figure 23A, with a red line indicating the error in the performance. The mistake comes from a bent kua and a dropped hip as Master Chen changes the height of his stance. |

|

Next, Master Chen demonstrates the proper structural adjustment according to Taiji principles. He maintains the rear hand and foot connection, reinforces the rear anchor line, and tucks in the tailbone so that the rear kua no longer folds. This correction is shown in Figure 23B, where a green arrow marks the tucked tailbone and the dotted green line emphasizes the relationship between the rear hand and rear foot.

He asks his student, “Can you feel it [the rear structure] is not broken? So this [right hand-right foot] is connected all the way. Can you feel [the structure] from the [right] finger to there [where your hand is on my right calf]?”

Master Chen then returns to a normal position and explains, “[If I just deviate a little bit from Taiji principle,] now see how it [the structure integrity] is all lost. You feel it’s lost.”

He concludes, “The front and the back, the two lines [connecting the hand and foot must] never break up.”

Master Chen provides another example of an energy break by examining Movement 4. He begins by explaining the action: “This one here [right hand] extends, and turns toward the left to bring the right hand back to the centerline.”

|

Next, Master Chen instructs his student: “Now you grab me here, and hold my ankle. I’ll make it [the entire movement] smaller for you to feel [the energy].” Figure 24A highlights the resulting error: a red dot shows the lack of connection between the rear hand and rear leg, and a red line across the kua marks the folding of the kua caused by a change in stance elevation, which breaks the energy of the structure.

He asks, “Can you feel it [the energy from this action] is broken?” |

Master Chen then demonstrates the correct Taiji alignment. In Figure 24B, he repositions his body to conform to Taiji principles. A green dotted line emphasizes the connection between the right hand and right foot, and a green arrow shows the tuck of the pelvis that prevents the kua from folding.

He concludes by asking, “Can you feel that [hand-foot connection]? You feel that [sense of fullness of energy in the movement]?”

6. Meaning of Connection

After examining the details of Movement 4, Master Chen dives deeper into the concept of connection. He asks rhetorically, “So here [in movement 4], this [right] hand here is connected to your [right] foot. And in this case I’ll add, how is it connected?”

Master Chen answers emphatically, “Stretch.”

Master Chen provides more detail to his answer, stating “So this is what we mean by connection.” Returning to the previous physical models describing each half of the Positive Circle, he continues, “So there are two [scenario] here. Let me go backward in my talk here [to remind you what I have already covered], to complete the initial principle I talked about. The two kinds [of scenario] represent [the Taoist philosophy of] Yin and Yang. Meaning [in the first half of the Positive Circle], when my hand goes backward, I [need to] use the rubber [model to explain this action].”

Master Chen picks up the rubber cord again. “There was a reason [to use the rubber model], because that [first half of the Positive Circle] is a negative move, a negative move that preserves integrity but relies on this texture [that has the ability to stretch].” He asks one of his students to hold one end of the band while he holds the other. “This [rubber] texture. So [when] you hold it [one end of the band], you see here? [There is slack between the two points].”

|

He reminds his student that each end point represents a body part. “This [end] is the rear foot, this [other end] is the hand. They’re not connected [meaning the action of one end does not affect the other end]. So in this combination, how would they be connected? Like this.” Master Chen moves his end of the band away from his student’s and takes out the slack. “So I stretch a little bit [and you don’t move].” Figure 25A shows a green arrow indicating the direction of the stretch, a solid green line marking the stationary end, and a dotted line showing the reference middle. |

Master Chen describes a second scenario for creating a stretch: “Or I don’t move, you stretch [by moving away from me]. [Both scenarios shows that the hand and foot are] Connected.” This is shown in Figure 25B.

He then adds, “Now, let’s move together [equally away from a reference middle]. Yeah. [Still] Connected.” This third scenario appears in Figure 26A.

| He summarizes, “There are three scenarios. [Scenario] One, [the end holding by the student] doesn’t move, I move. [The result, both ends are] Connected. [Scenario two] I don’t move [at my end], you move. Connected. Now the next one is actually quite difficult [to achieve]. Because this [rubber band] is a physical object, it’s easy [to create the stretch], but on the body, it’s very difficult. Meaning [in the last scenario,] these two [end points must] move together.” Master Chen demonstrates again: “Now let’s move together, you see?” Figure 26B shows red arrows indicating that the movements are not equal or aligned. |

|

He concludes, “Can you see it’s not connected [between the two ends]? So, meaning [in the third scenario, when the two ends are moving], they must be [moving] exactly [in] the opposite direction [and] on the same line.” Reviewing the movements in Figure 26A, he says, “Move like this [where both ends move equally away from each other]. Connected.”

Master Chen explains, “Everything has to be on the same line. So this is central to our system, and it’s this kind of a stretch. It’s called a concentric stretch. The definition is that the stretch must be on the same line between the two points, and it must go in two opposite directions on the same line. The two ends [cannot] move randomly. So this is the negative [aspect of the Positive] circle, meaning [the action is carry out by] going backwards.”

He continues, “When you [your actions and your hand] go forward, I use this [the stick model]. There’s a reason I don’t use that [rubber band model]: the negative one is connected, rubbery, and soft. That belongs to a type of energy in Taiji we call pulling. Whenever you pull, you must feel the energy exactly that way.”

Master Chen refers to the rubber band model. “[Initially, one rubber band connects the two end points.] [As you improve,] imagine [there are now] two rubber strings in front of you. Grab them and feel how they stretch [the resistance from two rubber bands is more than the initial one band]. That stretch [from one rubber band] represents the beginner stage. With training, your strength increases [correspondingly you can now stretch two bands], but the nature [of the action] remains the same—rubbery. This is what we call the yin type of energy.”

Master Chen continue with the same analogy. “You [again] double the strength of the rubber cord so it [resistance of the rubber band] feels almost stiff, yet its quality remains soft, [but] extremely strong. In our physical world, I compare this to the hard rubber threads on a tire. They grip cement, tarmac, or asphalt so effectively that they power movement. They are not soft like water but firm, and still very different from the steel components inside an engine.”

Master Chen reminds his student, “[Yin and Yang,] they work together. [An engine could be made from steel], but it still contains yin parts and yang parts.”

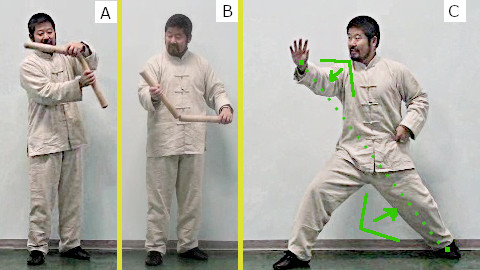

Master Chen returns to the discussion of the second half of the Positive Circle, focusing on the movement “Out with Hand.” He begins: “The Yang part [of the Positive Circle] is on the way out.” Master Chen refers to the stick model shown in Figure 07 , which uses two sticks to form an open triangle. He reviews the model: “Here [the stick model], it [hand movement] is this here [due to the movement of the apex of an open triangle]. And [require] this one here [the anchor at one end of the triangle and a fixed track motion on the other end].”

Master Chen reminds his student: “It [the stick model] has to be two moving [components, the apex of the triangle and one end of the triangle moving on a track. There is also one fixed component which is an anchor for the triangle].” He continues: “[There are] three or four [such triangle structures] on your body, but [the side of each triangle] has to be the bone.”

Master Chen emphasized the importance of having the correct model as the basis of your action. He explains: “Replace it [the model] and [I will] show you why it [the model] wouldn’t work [in describing the action].” Using the same setup previously used to explain the two models, he describes the situation: “This [end held by the student] is one anchor point. This [end that I am holding] is another anchor point. Don’t move. Lock it. And in the same configuration, instead of two sticks,

|

I use a rubber [band to connect the two end points]. [The action of pushing the middle towards the end] it won’t work.”

This is illustrated in Figure 27. In the figure, it is clearly shown that the rubber band connecting the two points is not taut, so the action of a push cannot influence the two end points. Master Chen concludes: “[In this situation involving a push,] I need two [sticks] there.” |

Master Chen then explains the reverse situation, where an action involves a pull. He begins: “Now, let’s change it [the model] here [replacing the band with two sticks connected into a shape of an open triangle]. If the same configuration, but I do this [push onto the apex of the triangle], it won’t work.”

| Figure 28 shows Master Chen’s action as he pushes the apex of the triangle, causing one end of the stick to rise. He continues: “You [the student at the other end of the triangle] don’t feel anything [because all the power is dissipated in the movement of the other end of the triangle. There is no pulling action]. Why? Because pulling requires that rubbery feeling. Pushing requires here [a rigid structure].” |

|

Master Chen concludes: “[In the Practical Method of Foundation practice,] when you train the Circle, the Positive [or] Negative Circle, imagine the two qualities [of rubber and stick]. ”

Master Chen delves deeper into the philosophy behind the two models. He begins by asking rhetorically: “On your body, what are we training? [What does the rubber and stick represent?]” Master Chen then explained. “[Action towards the body requires a pull which uses a rubber characteristic. In Taiji this characteristic is classified as Yin.] Yin [in the body] is ligaments, tendons, including—you can never get rid of—the muscles, because they [all] act as part of that group. [Action away from the body requires a push which uses a stick characteristic. In Taiji this characteristic is classified as Yang.] Out is with bones.”

Master Chen then applies these two characteristics to a Taiji technique. Reiterating the words of Master Hong: “The concept of Yin and Yang is part of the interplay.” (陰陽理;互變中) Master Chen explains: “We constantly switch between [Yin consisting of] ligaments, tendons, that type of energy, and [Yang] the bone energy.”

|

Master Chen then went on to provide two examples of this type of switching in a Taiji technique. In the first example, Master Chen instructs his student to grab his front right wrist and place the other hand on the side of Master Chen’s body. The position is now locked, and this initial setup is shown in Figure 29A.

Master Chen continues: “If I do this [turning the forearm to try to pull the student’s body down], can you see what I’m doing? |

Yeah. I’m using ligaments and tendons. That’s wrong. But see, feel. There is nothing there.” This action is illustrated in Figure 29B, with the red arrow showing the pulling action of the forearm.

Master Chen then demonstrates the concept of switching. He explains: “I just realigned the bones, and it gives me that power.” This action is shown in Figure 34C, with the green lines and arrows indicating the rigid structure that pushes the student away.

| In the second example, Master Chen instructs his student to hold him at the wrist and place a hand on his side again. This initial position is shown in Figure 35A. He describes the situation as follows: “[The opponent is] on the way in. If I do the wrong way again, see we are here, I’m supposed to use ligaments and tendons on the way in, but [instead I incorrectly] adjusted the bones. You don’t feel anything.” This result is shown in Figure 30B, with the red lines and arrows indicating the incorrect actions of the bones. |

|

Master Chen then performs the proper Taiji Yin action, stating: “But now, see like, can you feel I’m torquing the ligaments, tendons, and the muscles?” This is shown in Figure 30C, with the green arrows illustrating the correct pulling actions of the ligaments.

Master Chen concludes: “I have to go on and off with that switch. So these are very, very important qualities we have to learn through the Yi Lu form to manipulate.”

Master Chen alludes to a deeper philosophical concept associated with this type of training. He explains: “Some people call this [action] on-off, on-off, but in reality, it’s always on [something]. It [action] is this on [the ligaments] or that [action is] on [the bones].”

|

Master Chen clarifies this idea by using a light switch as an analogy: “So to speak, even the light switch is not [described by an] on-off [action]. This [switch] is on, so the light turns on. Or this [switch] is on [the off position], so the light doesn’t turn on. It [the switch] is simply in a different position. So technically, it [the light] is never off.”

Building on this analogy, Master Chen explores further implications, explaining: “The deeper |

|

understanding is that when you flip the switch up, it’s on with light. Flip it down, and it’s on with darkness. It’s not off. Because what we usually mean by ‘off’ is that it’s not doing anything. But it is doing something—it’s connecting to a source that doesn’t light up.” Relating this back to Taiji practice, Master Chen concludes: “And here it is, you’re either on the bone or on the ligaments. So you are never not on anything. That’s very, very important to know.” |

|

7. Homework: Mastering Hand–Foot Connection in Yilu

|

|

|