|

A young woman bathed in golden morning light cradles an overfilled coffee cup, dark liquid trembling at the rim. Outside, the day hums with warmth and possibility. Janis Joplin‘s raspy voice floats gently through the air “ My friends all drive Porsches, I must make amends… ”

A book tilts precariously on the table’s edge, caught between stillness and surrender. She sways to the rhythm, a sleepy figure outlined in light, shoulders hunched like soft question marks. Then, with a breath drawn deep, she rises, posture aligning with purpose, as the music murmurs, “ Worked hard all my lifetime, no help from my friends…” |

| Her stomach stirs. Breakfast, forgotten, now calling. She reaches for a curved knife, aiming at a watermelon. On a whim she pivots, selecting ripe fruits instead. The blender whirs, a mechanical harmony to the fading echo of Joplin’s blues. As if on cue,a synth swell ripples through the air, Frankie Goes to Hollywood crashes into the moment. The provocative lyric emerges from the haze, “ But shoot it in the right direction / Make makin’ it your intention “, bold, insistent, electric. The sound urges everything to become louder, brighter, bolder. She lifts her headphones and places them aside like a relic from another mood. A new rhythm begins. She opens her laptop. The glow of the screen spills across her face, quiet and curious. The title flickers: Master Chen’s Workshop. She leans in as the video begins …… | |

| (This is Part Three of an edited transcript of the Basic Principles of the Positive Circle in the 2013 Workshop in Sacramento sponsored by Carmen Farrugia.) |

|

|

Part 2. Relaxation does not exist

Part 3. Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?

|

Part 1. Every motion must follow a prescribed pattern

Part 2. Relaxation does not exist

Part 3. Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz?

11. The 1-2-3 of the Positive Circle

|

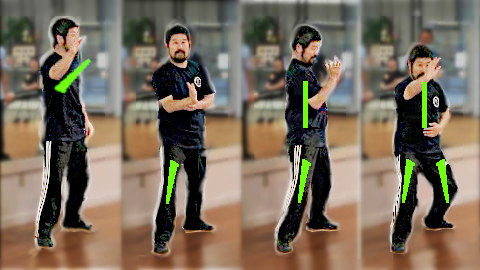

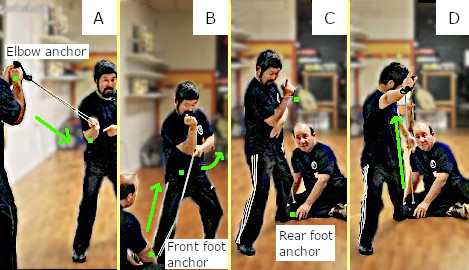

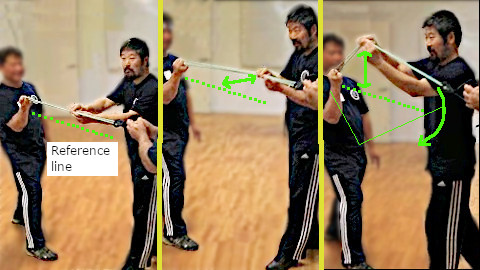

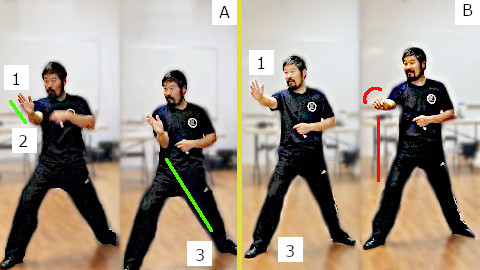

Master Chen then links this concept to the execution of the positive circle. “The first one [‘In with Elbow’] only [involve] this one side [the front elbow and leg]. This movement here [the action of pulling in the elbow] is the equivalent of this one here [stretching from the front foot to the dantian].” The first panel of Figure 34 illustrates the elbow withdrawal, indicated by a green line. He demonstrates the stretch by adjusting his ankle to create a sharp line extending from the front ankle to the front elbow. |

This is depicted in the second panel of Figure 34, where a green line highlights the stretch originating from the front ankle. Remember, the hands and feet are mirror images of each other, so they are regarded as one body part.

Master Chen continues, “Second time [‘Turn with waist’], this one [front foot] works together with this one [centerline]. That makes two [body parts working together].” This is illustrated in the third panel of Figure 34. He then explains, “Third time [‘Out with hand’]: one [front foot, front hand], two [centerline], three [rear leg]. [The third action of the positive circle,] all three [of the body parts works] together.” This is depicted in the final panel of Figure 34.

Master Chen summarizes, “So the first move [for the Positive Circle involves] one body part. The second move [uses] two body parts. The third move [involves all] three body parts. You get that now? It’s very, very important that you don’t involve all three from the start [for training the Positive Circle]. When you engage all three [body parts] in the final move, it’s called whole body movement.”

He continues, “If you start [the Positive Circle] with [all] three [body parts], [from the Taiji perspective,] it [the action is considered to be] double heavy. If [your action of the Positive Circle] ends with only one [body], it [this action] is also double heavy. [For the positive circle, you must start with one and] you must finish with all three.”

Master Chen concludes, “Start with one. Move to two. Can you see this [front leg] and this [centerline]? They work in unison. And finish with all three. These are the basic three steps of the Positive Circle. So now you understand? Let’s try it.”

Master Chen reviews the ‘Self-directed Positive Circle’ while guiding his students. He begins, “[Number one is] Hand out. No move. Only the [front] arm comes up. Come back [with your elbow], with your [rear] hand assisting. Return [with the elbow]. No body movement. Not even your eyes. It [elbow] must come in front of your body. Your elbow cannot go behind your body. This [placement of the elbow] feels very awkward [at the beginning]. [Nevertheless,] it [the elbow] must come to the front.”

He continues, “Number two is when you turn [your waist], you’ll feel the front leg begin to push [the front side into the centerline].”

“For number three [‘Out with hand’], as you extend [your hand], push here [front leg], and push here [rear leg]. All three [body parts must] work together. The three [working together] is very difficult because the body parts must be balanced. We tend to overemphasize this one [front hand powered by the centerline]. That [rear] leg also powers up easily. But this one [front leg] often gets ignored.”

Master Chen offers a final reminder: “ These three parts must be equal. One third, one third, one third action. They must be equal—yet no single part should move. ”

12. Move is displacement. Don’t move is rotation.

Master Chen delves into the concept of movement within the Practical Method system. He defines “move” as a change in location: “Move is displacement of location. They [each body part] can rotate, but they cannot move.” To clarify, he gestures toward his rear kua. The femur (thigh bone), being part of a ball-and-socket joint, is capable of rotation within the hip socket, yet the hip itself remains fixed in place. He explains, “This [femur] is in here [the kua]. It can do this [move within the hip socket].” Master Chen then illustrates a hinge-like action with his hip, visibly shifting its position. He notes, “But this [action of the hip] is a movement. So you cannot move.”

Master Chen expands on the principle of movement in the Practical Method system: “Move is displacement of location. They [each body part] can rotate, but they cannot move.” To illustrate, he gestures to his rear kua, explaining that while the femur (thigh bone)—a ball-and-socket joint—can rotate within the hip socket, the hip itself should remain stationary. He clarifies, “This [femur] is in here [the kua]. It can do this [move within the hip socket].”

|

Demonstrating further, Master Chen performs a hinge-like motion with his hip, visibly shifting it from its original position. He states, “But this [action of the hip] is a movement. So you cannot move.”

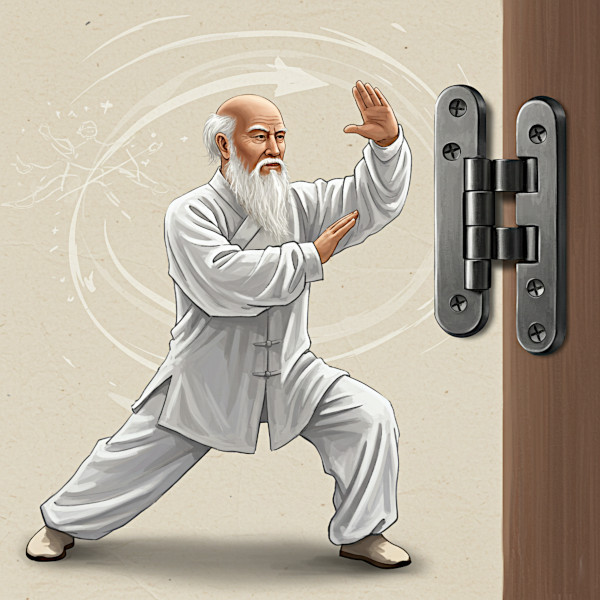

To clarify the concept, he presents a physical analogy: “Like a door—when you open it, the hinge remains fixed [serving as the pivot point or center of rotation]. Opening the door doesn’t imply it [the door] shifts position [forward or backward away from the door frame]. [The door is rotating due to the hinge.]” Figure 35 illustrates this analogy with an image of a door hinge. |

“From an engineering perspective,” he notes, “rotation is defined as movement without dislocation of space. In Taiji, all movements must adhere to this principle of rotation. Observable motion may occur, but there must be no displacement of location.”

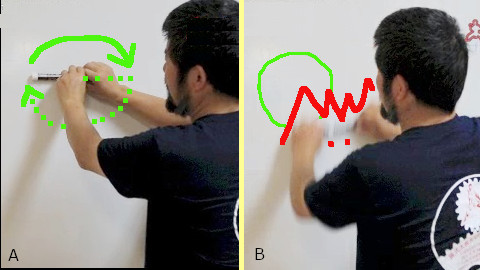

| In Figure 36A, Master Chen illustrates the concept of rotation using a marker. He places it on a drawing board, anchoring one end to act as the center of a circle, and rotates the other end around this fixed point. He narrates the demonstration: “Meaning, when you have this here [a marker on the board]. If you lock this point [one end of the marker creating a center] and rotate like this here [the other end of the marker]… So it means now [the rotation of the marker around the fixed center] I make a circle.” |

|

After completing the circle, Master Chen continues, “The circle is here. Once you finish it, you notice the pen—the marker—its movement stayed within the circle. Not one part came out. [The creation of the circle by the marker,] that’s movement without displacement of space. [Everything within the perimeter of the circle,] this is the space prescribed for it [the circle].”

In Figure 36B, Master Chen draws red lines outside the circle to highlight the contrast between the circle’s defined perimeter and irregular linear movements: “But if you go like this [moving the marker up, down and or sideways], that’s movement. [In contrast,] if you go like this [rotate the marker about a center], everything stays where it is. You do it again [keep rotating the marker about the same center], it [the circle] is still there [the perimeter is always being retraced]. Nothing ever comes out.”

Master Chen then summarizes the definition of movement in the Practical Method: “ As long as you meet those characteristics, you are not moving. This is why it’s very, very difficult for people to understand why in Taiji you don’t move, yet it appears as though you are. You’re moving, but you say you’re not moving. Now you understand?”

|

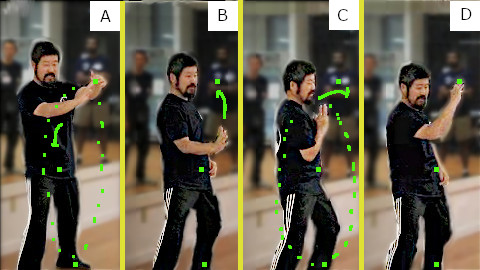

Master Chen demonstrates the concept of movement by performing the Positive Circle in Figure 37A, using the front hand while the rear leg marks the circle’s perimeter, with the dantian serving as the center. He begins: “[In the beginning, the front arm is extended.] This here [the front fingertip]. My arm is this long—you can see the circle is defined here [from the front fingertip to the rear foot].” In Figure 37B, he continues: “[You make the second move. ‘Turn with Waist’] Now, can you see it [hand] is inside [the original circle]?” A green line in the figure illustrates this. |

Master Chen proceeds in Figure 37C: “[You continue with the third move, ‘Out with Hand’] Now, can you see here [your hand ends back on the perimeter of the original circle]?” Upon completing the Positive Circle in Figure 37D, he explains: “Next time, [you continue to perform the sequences] can you see there is [always] a circle here? I’m inside.”

| Master Chen then contrasts correct execution with improper movement, as illustrated in Figure 38. The red lines trace the path of the hand. He explains: “If I do this [any action that does not follow the initial circle], any way I want to [even though it might ‘look’ circular but it does not follow the properties of a circle], it [the action] came out [of the original circle]. If it comes out, that’s a movement. If it stays in, it’s not a movement.” |

|

Figure 38 shows that this motion does not involve the dantian or maintain grounding, unlike the Positive Circle. He elaborates: “That’s why we say don’t move. If you don’t understand the meaning behind this, it may look like you’re moving—so why say don’t move? Because it’s movement without stepping outside its parameters. The circle is the boundary for rotational movement.”

|

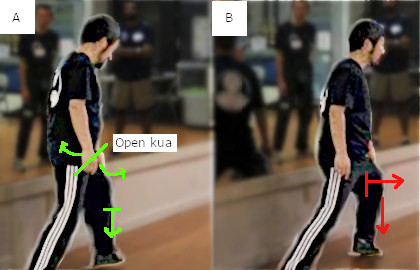

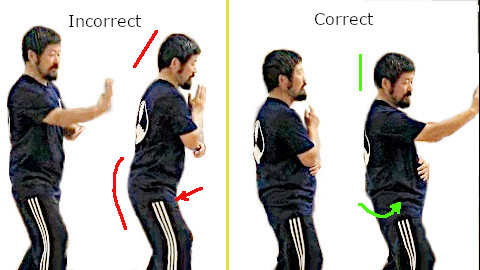

Master Chen elaborates on the concept of movement parameters, stating, “There are other movements that also have parameters.” Stepping into a lunge position, he continues: “Let’s say here [in a lunge position]. If you go like this [push the knee forward], that’s a move.” This movement is illustrated in Figure 39B, where red lines indicate the error of the knee moving forward despite increased downward pressure on the foot.

He contrasts this with the correct form shown in Figure 39A: “[If] you go like this [the knee is kept stationary but the hip is pushed forward onto the knee], this is not a move.” |

The green lines in Figure 39A highlight the opening of the kua, which generates downward pressure through the foot.

Master Chen adds: “There is a very small action from here [at the knee], pressing firmly down into the floor. That’s not [really considered to be] a movement. But in reality, there is a movement [of the knee] going downward. That [strict definition for the knee] doesn’t matter because you’re not doing this [wobbling or moving backward and forward with the knee].”

Master Chen emphasizes, “It’s very, very important in the beginning stages of the Practical Method to clearly distinguish what movement is—and what ‘don’t move’ means. ‘Don’t move’ refers to rotation. Visually, your eyes will perceive movement, but it’s confined within the prescribed area. That concept is very, very important.”

He explains further, “Without fully understanding this, and without rigorously subjecting your body to that rule—repeating it until your body never violates it—you don’t have Practical Method. You’re just doing what everyone else is doing: waving your arms.”

“People often say that after years of practicing Taiji, it still feels like they’re just waving their arms and aren’t really sure what they’re doing. That’s because there’s no standard. But once a standard is established, you can move. And once you follow that standard, you’re no longer just waving your arms.”

“There’s no mystery in it—no magic formula like ‘putting energy in it.’ That doesn’t exist. Just follow the rules. When you follow the rules, the energy is correct.”

| Master Chen uses a keyboard analogy to underscore the importance of obeying rules and staying within defined parameters. He explains, “In computer science programming, you can be very smart. [Still] you’ve got to follow the rules of programming. You can’t just do whatever you want. I don’t know programming, but I [still] use a computer. If I want to type J, I’ve got to use this finger and type the J. I can’t just say, this morning, I like [the letter] K. I will [then arbitrarily] say, [from now on] K is J. If you don’t agree with me, [I will argue] I’ve got my rights. It [life] does not work like that. Because [when] you push K [on the keyboard], K will be on the screen. |

|

[Even] if you get mad and kick the computer, it does not listen. The computer is very, very patriotic. It will say, I will [rather] die, but no J will come up [on the screen when you press K on the keyboard].”

He elaborates on the lesson behind the analogy: “Seriously, our human life is such that you can be wrong and you don’t [have to] agree [with others]. We have to deal with that [natural tendency to compromise and avoid confronting rules and limits]. Unless you subject yourself to the rules, you cannot make progress. [It is true that] you can do whatever you want. Nobody can stop you. [You have to ask yourself,] what are we trying to do? Learn something [in this particular system]. So learning something [means] if you want to type J [on the keyboard], [what appears on the screen] is J. J is not K [no matter how much you want it to be]. So [what we have practiced,] these are the rules [for the Positive Circle].”

He concludes, “Let’s do the three count again: In with the elbow, turn with the waist, out with the hand.”

13. Circles are triangles

Master Chen said. “As you perform the three movements, keep your gaze fixed in one direction. Avoid looking at your body. If your eyes stay steady, your body will naturally rotate. However, if your eyes shift, your body will not rotate.”

|

He continued. “Every action must have Yin and Yang. I’ll show you why we do these three actions.”

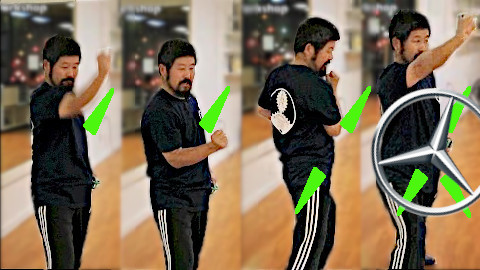

Master joked. “My dream is that one day, I will buy a Mercedes and give it to a man living under a bridge. That’s my dream. One morning, that man—who has been begging and sleeping beneath the bridge—wakes up to find a set of keys beside him and a Mercedes-Benz parked nearby. That’s my dream, a simple one. I believe [Mercedes is] a truly exceptional car. It bears that [logo] symbol, which is [exactly the same as Taiji], representing the principle of three energies.” |

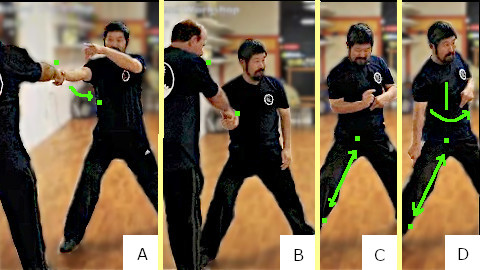

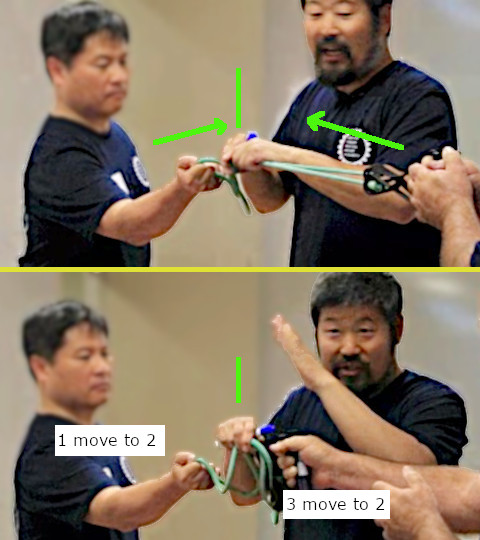

| Master Chen demonstrates each exercise with clear physical examples. In Figure 42A, one of his students holds his leading hand while Master Chen stands in the ready position. The green arrow highlights the direction of the elbow drawing inward toward the body. He explains, “You stand right here and grab my hand. He is the nail. The first one [‘In with Elbow’], I pull him this way [with my elbow into me]. This [connection between the hold and the elbow] is the line.” |

|

Figure 42B illustrates the strength generated by the elbow, showing how it can pull the student forward. Master Chen advises his students that when training solo, they should imagine a physical anchor and exert force against it.

Figure 42C captures Master Chen moving on to the second technique. He describes the motion: “Number two, when I turn with my waist—can you see what happens? I’m hitting that nail on the floor. This here [on my front ankle].” The green arrow in Figure 42C indicates the pull directed toward the front foot, while the image also emphasizes the action of waist rotation.

|

In Figure 43A, Master Chen demonstrates the concept of force lines using an elastic band as a visual aid. He instructs his students to hold one end while he holds the other, positioning the elbow anchor point approximately 45 degrees from the Dantian. He explains, “My [first] action [‘In with Elbow’] is pulling [the elastic band] against that nail on the wall. It’s not like this [random movement of the elastic band. There is a fixed start and end points creating a line]. |

There is a line here coming toward the Dantian. That’s the first line—one-third of the way toward earning a Mercedes Benz.” The green arrow in Figure 43A shows the direction of the pull.

Figure 43B shows the student repositioning the anchor point to the front ankle. Master Chen continues, “Number two, [the second action ‘Turn with Waist’]. Can you see my elbow came here [into my body after the end of the first move]? It [the elbow] became part of this here [my body]. When I turn the waist, can you see the work [of elastic band being stretch because it is anchor] on that [front] foot? So, that [anchor point on the foot is] the dot. From that dot, I created this line [a line stretching from the front foot to the Dantian]. So one line [from the first movement] and the second line [from this movement] has now been created.” The green arrow in Figure 43B illustrates the stretch from the front foot anchor to the front kua, maintaining tension through the rotation of the waist.

In Figure 43C, Master Chen instructs the student to shift the elastic band once more, anchoring it to the rear foot. He explains, “Number three, [‘Out with Hand’]. Everything powers up [maintain the structure created from the previous two movements. Then proceed to carry out the action of ‘out with hand’ which] created this one [line] here [stretching from the rear leg to the front hand].” Figure 43D displays the final stretch, extending from the rear foot anchor to the front hand.

| Figure 44 concludes Master Chen’s demonstration: “I focused on this [first] line [created by the elbow pulling into the body at a 45-degree angle], this [second] line [formed from the front foot pushing into the body, creating the turn of the waist], and this [third] line [resulting from the rear leg pushing the front hand out]. These are the reasons behind the three movements. All three are directed towards here [towards the Dantian]. |

|

When they [the movements] are like that [clear and distinct], they resemble this symbol here [the logo of the Mercedes-Benz]. That’s the reason for those [three] movements [of the Positive Circle].” The green lines in Figure 44 visualize the virtual force trajectories produced through the Positive Circle movements, culminating in the formation of the Mercedes-Benz logo.

Master Chen offers a cautionary note: “Make sure you are not moving. See, watch. [When your movement is not on the prescribed line,] everything is lost.” He then demonstrates the three correct movements and asks, “Can you see the three straight lines? These straight lines will form a triangle. The triangle is the circle.” [With this simple statement, Master Chen alludes to the geometric relationships between triangles and circles, such as every point on a circle corresponding to an angle in a right triangle. A triangle can be inscribed in a circle so that all three vertices touch the circle’s boundary. Conversely, a circle can be drawn around a triangle, touching all three vertices to form a circumcircle. This relationship also forms the Mercedes-Benz logo.]

|

Master Chen shares an anecdote to illustrate the fundamental connection between triangles and circles: “Last night, I had the unexpected pleasure of being “kidnapped” by a Chinese scientist. He holds a PhD in rock geology but now works in software development. He never got to apply [his specialized degree]. When he saw my Taiji demonstration, he remarked, ‘That’s what we study.’ He continued, ‘In foundational rock geology theory, three lines must be present. When they form in that way, it becomes a circle… [just like the] Mercedes [logo], with three lines and a circle. That concept is the bedrock of all science… mathematics originated from it… everything stems from that.’ |

[This geologist concludes:] ‘It’s amazing that you talk about that in Taiji.'”[The geologist is probably alluding to geological concepts such as stress and strain axes, fault and fold classification, and deformation types—all fundamental principles that depend on three equally critical components.]

Master Chen describes his response to the geologist: “I’m not talking about that [math or science fundamentals] in Taiji. I’m simply repeating what my teacher passed down to me—just as he was repeating what his teacher had taught him. When Taiji was created, it was a science of the body, not of rocks. It was a real science, but its focus was the human body, not physical materials. They could have pursued diamonds. No. And become rich? No. I don’t know what else they might have done.”

Master Chen observes his students practicing and offers crucial insight: “Don’t move your head. Watch the power [of the move]. When this structure [the triangle]—especially the head—remains intact, do you see the power? But if I do this…” He demonstrates by bending at the waist. “Can you see that when the head moves, the power is lost? Can you see the structure? [‘In With Elbow,’] don’t move your hand. Only move your elbow. Do you feel that flow? If you move your hand, that flow is lost. So — elbow-in.”

“[In the second move,] ‘turn your waist.’ Don’t toss—turn [your waist].” Master Chen uses a door as an analogy to emphasize the importance of controlled movement: “I never moved. I’m stronger—like opening a door. Opening a door doesn’t mean the door is going to fall down. It’s essential that your movement is like opening a door. You do not do this [tossing].” Master Chen then illustrates the incorrect motion by shifting the centerline.

“I’m very grateful to all of you for attending the workshop and taking the time to observe what I do. This [type of Taiji training] is very different from what others practice. I’ve faced criticism [for this type of training], but that’s okay—it’s not my fault. It’s what my teacher taught me. [Most of the criticism of my Taiji] is that it appears very stiff, because [in contrast] most people prefer this kind of thing.” Master Chen then demonstrates a series of random movements that resemble Taiji but do not follow the principles set by the Practical Method.

“When you finish [the three count of the positive circle], don’t [let your leading arm] go straight [meaning locking the elbow],’ Master Chen begins, explaining the reasoning behind this caution. ‘I asked you at the very beginning to experience what straight is. [I instructed you to reach out with your lead hand] so that your hand is straight. [But remember once you understand this idea,] then you [relax the elbow and] move [the hand] here [in line with the front toe. This is the actual starting point for the positive circle]. When you finish, you should always be here [back at the initial starting point].”

Master Chen emphasizes, “ The elbow should never be straight. ”

To illustrate, he demonstrates an incorrect movement: “Look at everybody—especially during a fight. Everyone is doing this [pressing with straight arms and wrist bent]. Totally straight [for the arm], and bending here [at the wrist]. Many [martial arts] styles do that. That’s their specialization. But I do not understand their theory behind it—they have their own approach because they use power differently.” He reminds his students, “Our physical structure requires this [wrist and forearm] to be like a knife. Movement comes from here [the elbow].”

Master Chen reinforces the concept once more and adds, “In Taiji, if you straighten [the elbow] here, your shoulder will pop [move out of the shoulder structure]. You are only here [within the natural support of the shoulder structure].”

Master Chen continues observing his students’ exercises and offers an important correction: “Too many movements. Just in [with the elbow]. You’re used to it [moving other body parts other than just the elbow]. We have to gradually change [this habit]. This is what you did.”

Master Chen then demonstrates ‘In with Elbow’ while deliberately involving unnecessary movements of the head, fingers, wrist, and other parts of the body. He explains, “Everything is moving. [The correct training for this exercise is] no move—just come in. Trust your elbow. The job of the first move is elbow. The job of the second move is waist. The job of the third move is hand–rear-foot connection. Stretch it [the front hand] against your rear foot. Power is there [when you have that stretch].”

“Master Chen noticed an error in one of the movements and offered the following correction: “You moved. I’ll show you why. Watch my chest.” He then demonstrated an action in which the chest visibly pops up in an attempt to generate power. “This [pop up of the chest] is called move.”

Next, Master Chen contrasted this with proper alignment—where the chest stays in line with the front hand and rear foot. “Can you see there’s a stretch? So do not go like this [movements that deviate from the main action].”

He reminded his students: “ We all have that move [that distracts us from the main desired action]. Just force yourself to go through the subtle changes. You will be different. ”

14. Three Rings of Taiji

|

Master Chen explains the importance of maintaining the center and not allowing it to shift away from the centerline. He begins by defining the centerline and its associated bodily reference points: “You know what this is? I’ll tell you why. Okay? From [the acupoints of] Baihui (百会, GV20) to Huiyin (会阴, CV1), [creates] this suspended line [known as the centerline]. It’s a line [in two dimensions]. But a straight line is considered a dot [in three dimensions]. You understand that, right?” Figure 46 is an illustration of front view of the human body showing the centerline that connects Baihui to Huiyin. |

|

To illustrate, Master Chen picks up a stick and demonstrates: “Here you see a line. [When the line is perpendicular to the line of vision. When] I aim it [the stick] at your eye [the line is now parallel to the line of vision and you can only see that one end of the stick]. [What you see is no longer a line but] it’s a dot. So [in a line,] you can have many of these dots [on a] very long [line]. [However, a line] it’s just a dot when it’s right facing you. [More clearly, you are seeing the end of a line that is parallel to your line of vision.]”

Returning to the centerline, he emphasizes: “[Starting] on this dot Baihui here, that [line] just means vertically there are many dots on this [line] here.” |

|

To convey its importance, he draws a military analogy: “[Consider] the dot here [on the centerline] are all the headquarters [housing] the commander in chief [for your army].”

| Master Chen demonstrates a Practical Method technique consisting of simple, distinct actions: “When you are fighting, you hold it.’ That is, no other body parts should engage unnecessarily. He contrasts this with common errors where students mistakenly believe involving more parts of the body adds to the movement. He explains why this is flawed: ‘If you go like this here [move the centerline], it [this movement] means when you hear the noise, there is an explosion. The president went outside to take a look. It’s very dangerous. The president must sit here. |

|

All the other people—I don’t know who—but there are people in charge of going there, investigate, and come back, maybe use a cell phone. And you see, President, there is no problem. Just one of the tires blew.”

He concludes: “[A correct Taiji action,] it [centerline] must stay there. Let other things do the job. Now you understand? So, go slow. Don’t use power.”

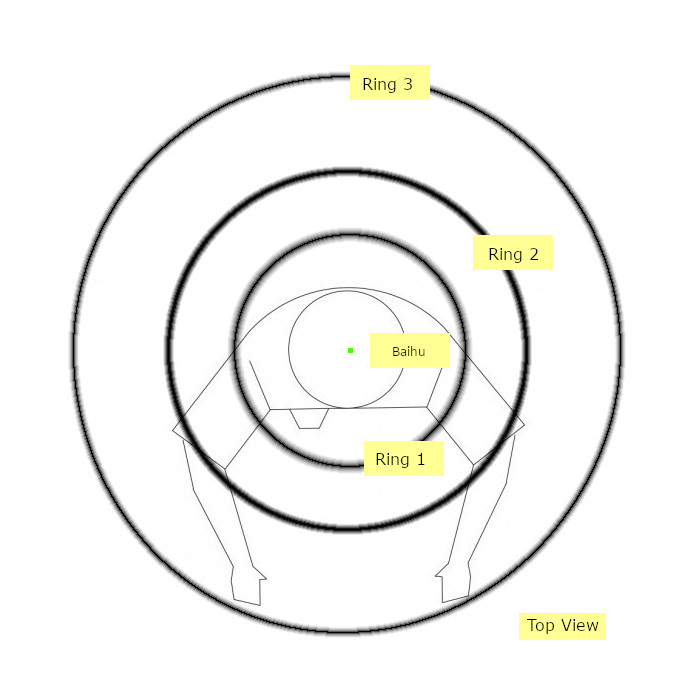

Master Chen then summarizes the concept known as the “Three Rings of Tai Chi.” He begins:

“The center must remain centered. It [the center] cannot deviate. This [concept] is called the ‘Three Rings of Tai Chi.’ Many interpret it differently. [Here is my explanation of this concept.]”

Standing in a ready stance, Master Chen continues: “[Consider an overhead view of my stance.] You will see a central column. [The center of the column is marked by a vertical line connecting the head, which rests atop the spine, down to the tailbone. The sides of the column are defined by the shoulders, which sit atop the kua. This represents the first ring.]”

|

He elaborates further on the overhead perspective:”Observe another column here [from the overhead view]. Notice how my elbows and knees operate within the middle range. [This range represents the second ring.] My hands and feet extend beyond [the elbows and knees. This range denotes the third ring]. The body consists of these three rings [when viewed from above—or three columns, if considered in three-dimensional space].”

Figure 49 illustrates this overhead view of the human body and the Three Rings of Tai Chi. Key landmarks include the Baihui at the center, the shoulders denoting the first ring, the elbows and knees defining the second ring, and the hands and feet outlining the third ring. |

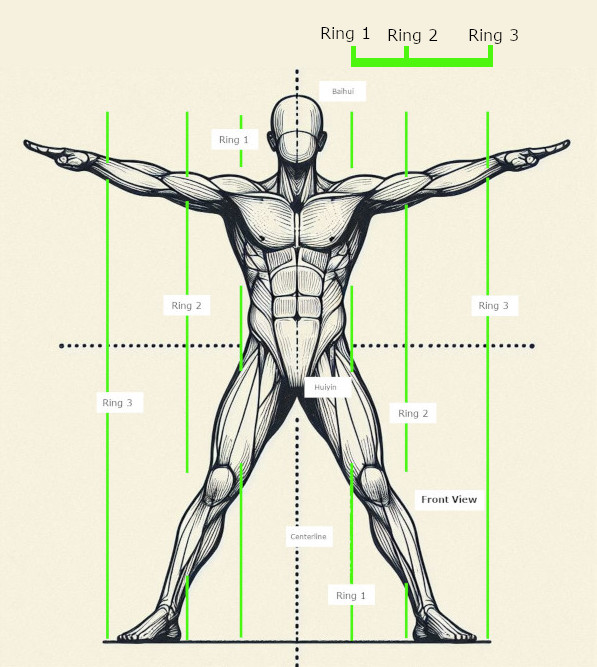

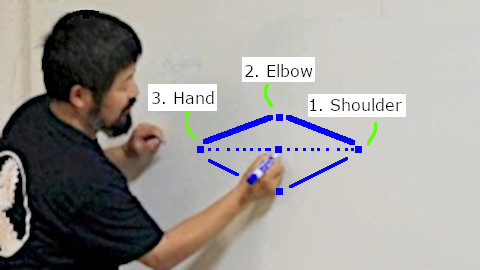

| Master Chen connects the concept of the Three Rings—derived from an overhead view of the body—to a straight line representation based on a frontal planar perspective. This visualization is shown in Figure 50. He explains:”[Each of] These three rings are called ‘One-Two-Three’. This is the ‘One-Two-Three’ … on a stretched-out horizontal line.” Using his illustrations, Master Chen demonstrates the direct correspondence: Ring One (the Center Ring) aligns with Point One on the line and represents the shoulder. Ring Two (the Middle Ring) corresponds to Point Two and represents the elbow. Ring Three (the Outer Ring) matches Point Three and represents the hand. |

|

|

Master Chen uses the concept of selling a house to convey the philosophy behind the Three Rings. He explains. “You’re a realtor. The first one is the middle [center ring]. [In realestate, this] middle [center ring] is the fixed asset [such as your house]. It means when you [the body] are solid [then] you [with your action] cannot take it [the body away]. It is [staying] in here.” Master Chen made one of his students hold his body inplace and then move his arms to illustrate this idea. He then compare this action to an action where he is moving his body away from his students reference position. He explained. “[when I moved my body,] it’s like I sold the house and I’m taking the foundations with me. The buyer will say, you can’t do that. It’s like you can take your car because you can drive it away [but] you can’t take the garage. |

The garage is part of the house. [The body, the center ring] is on the floor. [In three dimensions, this ring extends ] from the feet, all the way to here, The armpit. This [center ring] is the [fixed] asset. The asset is in the middle. ”

Master Chen continues by explaining the importance of the second ring. “This joint here [right elbow], this joint here [right knee], this joint here [left knee, finally, this joint here, left elbow]. [Each joint] is [a] matchmaker. The matchmaker is the negotiator. The negotiator [follows one rule which] is that the inside here [the dantian] cannot move.” Master Chen uses an analogy to explain the importance of this rule. ” [The dantian is] like the president, [he] can never leave the safe house, but he [still] has to know what’s going on out there.” Master provides actions to illustrate this action. ” [The dantian] send this [request for information] out [to the front elbow]. This is the [request for] information [as the front elbow extends]. Then this here [the elbow] will take the information [received] from the hand. [The withdraw of the elbow] come back here [to the body]. [The information] it goes here [back to the dantian].”

Master Chen compares this chain of actions to an incorrect response. Noting that “So you cannot do this [extends your hips forward]. [The analogy is that] The president here [at the dantian] wants to know. It cannot do this [move out of his safe house and take a peek outside].”

Master Chen described an andenote for the importance of this idea. “[I posted a video showing] One of my students was pushing me on my arm and I went like this [reacting to his push with my arms] and [the resulting energy traveled] through him, he jumped [in reaction to the energy]. … [The action] I was showing [was to illustrate this principle of] one, two, three relationship, but [because of my student’s reaction] people thought that was Fajin. Fajin means issuing power. So there are 80 comments [on that video]. I never received that kind of royal treatment. [Most of my videos] I never even got three attack [comments]. [Haters gotta hate.] People don’t even care about me. [Whether its] good or bad. They don’t care. But this one [particular video] got lots because people say this is a fake Fajin, but I wasn’t doing Fajin. That wasn’t Fajin. I was showing this here [one, two, three relationship]. ”

15. 1-2-3 relationship

|

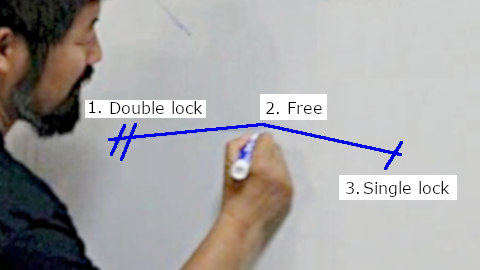

Master Chen drew a straight line and divided it into three sections, each marked by a point. This drawing is reproduced in Figure 52. He explains, “[On this line,] this is one, this is two, this is three—but this is a horizontal [straight line] explanation.” This is shown as a dotted blue line in Figure 52.

He continues: “In reality, [the line does not have to be straight. Each point corresponds to a part of the body. For example, one corresponds to the shoulder. Two is the elbow. |

Finally, three is the hand. Based on this correspondence in a planar action, one, the shoulder cannot move. Two, the] elbow can be here [above the horizontal line]. It [the elbow] can also be here [below the line].” These are illustrated as solid blue lines in Figure 52.

|

He concludes: “This one [referring to Point three, the hand] can be anywhere here. [This is] a rough static model [illustrating the 1-2-3 relationship]. Do you understand this here?”

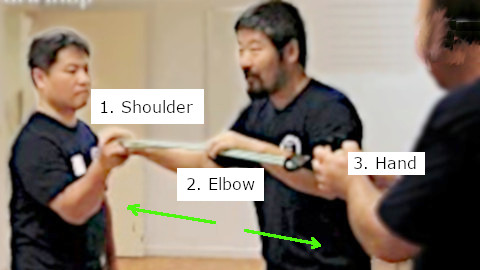

Master Chen illustrates this concept by having a student hold his finger, as shown in Figure 53. He begins by asking, “Can you grab me here?” The student grasps the finger, rendering it stationary—designated as Point 3 for reference. A dotted green line highlights the relationship between Point 3 and Point 1. He then explains, “If you follow me, can you see it [the elbow can] actually travels [with respect to the stationary finger.]?” Here, the elbow is identified as Point 2. |

|

|

Continuing, he asks, “Can you see it [the elbow] has a range [of movement in three dimension. The elbow can move in and out of the plane.]? This one [the elbow] has that range. This one [the finger] has this range. … This one here [the finger]—once I fix it—cannot move [but can rotate on a fixed point].”

In Figure 54, Master Chen performs the same demonstration without the student holding the finger. The outcome remains consistent: when the finger (Point 3) is fixed, the elbow (Point 2) exhibits greater mobility. Master Chen also reminds the students that the shoulder (Point 1) remains stationary. |

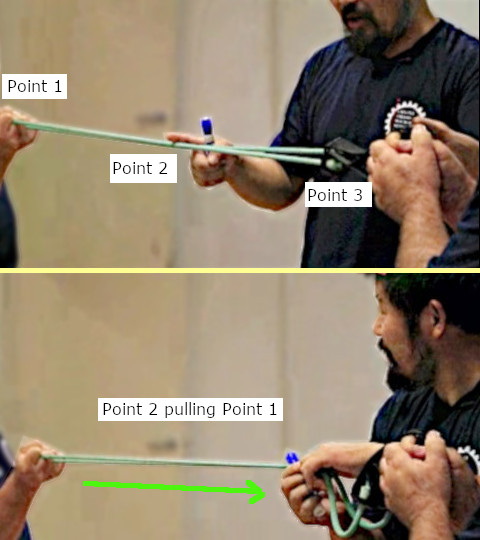

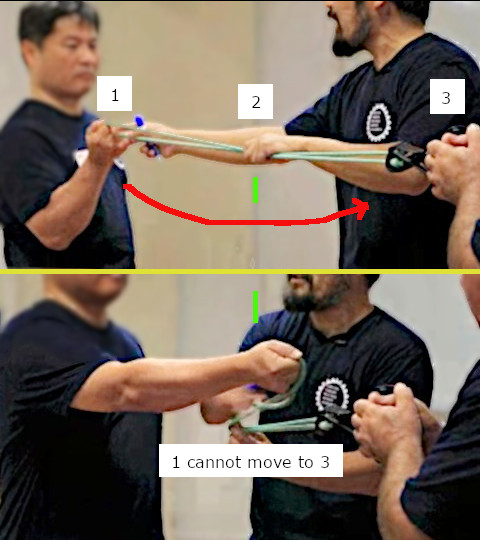

| Master Chen continues to demonstrate the 1-2-3 relationship using a rubber cord, as shown in Figure 55. He instructs one student to hold the left end of the cord and another to hold the right end. The left end is arbitrarily designated as Point 1, and the right end as Point 3. He then directs the students to move apart until the rubber cord is taut, with no slack. The tension is depicted as two green arrows extending away from each other, emphasizing opposing forces. |

|

He begins explaining the setup: “This is your shoulder [the left side, Point 1 it is]—very, very strong. This is your hand [the right side. Point 3 it is]—weak, but it does not move.”

Master Chen takes hold of the middle of the cord, referring to it as: “This is the elbow [Point 2].” He cautions that neither end should move, stating, “If you move [the end], it [tension within the cord] is lost.”

He then emphasizes the importance of maintaining tension, both for power and flexibility: “Can you see we produce the power? [When the tension of the cord is maintained.]”

|

In Figure 56, Master Chen alters the orientation of the elbow to demonstrate that it can be positioned anywhere in three-dimensional space while still maintaining the cord’s tension. He notes, “When you say sink the elbow, it does not mean one position.”

He elaborates further: “The elbow can do a full circle [but it is not] humanly possible,” acknowledging the physical limitations in the range of rotation for both the finger [Point 3] and the shoulder [Point 1]. |

He adds, “If you are doing math with no restrictions, it should be able to [move 360 degrees]. All you have to do is [for] you [to] turn your feet up and down, and [the elbow can now move without restriction. If you trace the possible paths for the elbow] there’s a circle, right?”

| Master Chen continues to emphasize the significance of the 1-2-3 relationship. In Figure 57, he introduces a schematic illustration of this concept, incorporating engineering terminology. Referring to a line drawing labeled with three distinct points, he begins: “This is called one,” as he points to one end of the line. “This is called two,” indicating the middle point. “This is called three,” pointing to the opposite end. |

|

He explains, “One and three are designated. One is called asset.” Using mechanical engineering symbols to represent their functions, Master Chen draws two sideways lines at Point One, explaining, “Two sideways lines … [means this point has] a double lock. In reality, it means [the line at Point One is fixed by] a screw on the wall, on the floor [or] on the wall. [This point] It cannot move.”

He then draws a single sideways line at Point Three and explains, “One [sideways] line means it [the Point Three] is on the rail. [The action for Point Three is] like [the end of] your bi-folding door [or] like [how] your shower curtain [moves].”

Master Chen emphasizes that movement along a track is essential but does not confine the track’s initial location. The starting position of the rail (Point 3) can be anywhere in space, but from that point on, movement must follow the track.

To illustrate this concept in Taiji practice, he explains: “Your hand, you think it moves [when I withdraw my elbow but according to the Taiji principle,] it [the hand] is [traveling] on the track. This [means the hand] does not move. [What you are seeing is the hand moving on the track.] So [the] hand is not free [to move randomly].”

|

Master Chen shifts the initial position of his movements but maintains the same path, demonstrating: “You can set the track here. Can you see your track is here?” He emphasizes that once the track’s origin is established, all subsequent motion follows that path.

He also notes that a track does not need to be linear. For example, in practice, the rails of a shower curtain can be circular. |

Master Chen returns to the physical model involving a rubber cord, as shown in Figure 55, to illustrate further properties of the 1-2-3 relationship. He reviews the underlying parameters of the model and notes the behavior of Point 1 and Point 3: “This [end point 1 or 3] cannot move sideways, but you can [follow the pull of the elastic cord and] come in.”

| In Figure 59, Master Chen explains: “No, you don’t [move in towards Point 2 by yourself]. [Point 1 is coming closer to Point 2] because when I apply sufficient pressure [tension], I’m causing [pulling] it [Point 1] to move [towards Point 2 in a straight line].” The green arrow in Figure 59 illustrates the movement of Point 1 being drawn toward Point 2 via the cord.

He reminds the student, “This [material connecting the points] is rubber. [So the force is a pull.] If this [material connecting the points] is a [solid such as a] stick, I push it [this stick] hard [on Point 2], you [at Point 3] will be forced out.” |

|

Concluding the demonstration, Master Chen affirms, “[You, at the reference point, can follow and travel with the force] But you cannot go sideways.” This forms the basis for exploring the relational properties among the three points in this model.

|

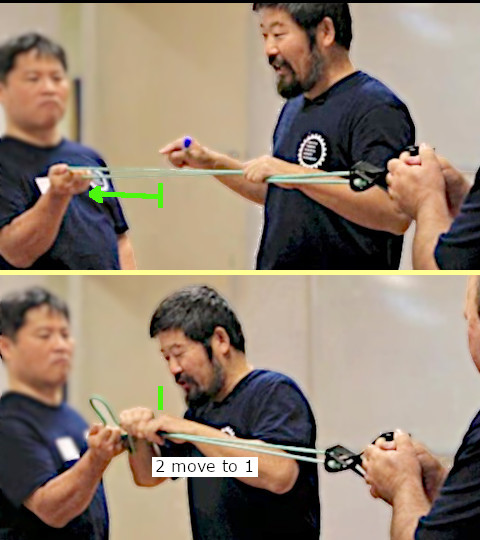

Master Chen demonstrates the principle that “1 can work with 2” in Figure 60 by physically moving the middle Point 2 closer to Point 1. It’s important to note that Point 3 remains stationary. The movement of Point 2 is linear—aligned with the cord—so the positions of Point 1 and Point 3 remain unchanged.

In Figure 61, Master Chen presents the same concept with a slight variation. |

|

This time, he instructs his student at Point 1 to follow the tension of the cord while he maintains his hold on Point 2. He tells his student, “Come here [to Point 2]. No problems.” He remarks, “Nothing changes.” In this scenario, both Point 2 and Point 3 remain fixed, while Point 1 moves linearly towards Point 2 by following the cord’s tension.

|

Master Chen continues, “Now, this is Two—hence, the negotiator. Two can lock.” He secures Point 2 in place and instructs his student at Point 3: “You can let go. No problem. The relationship is not lost.” This concept is illustrated in Figure 62: Point 2 remains fixed in space, while Points 1 and 3 can both move towards it.

Master Chen explains other iterations of this 1-2-3 relationships. He instructs the student at Point 3 to lock and remain still, while he physically moves Point 2 towards Point 3. He begins: “You [at Point 3], lock—no movement. I can do this [move my Point 2 towards you] and there’s no change. The pressure [cord tension] has changed, but no structural change [between Point 2 and Point 1].” |

He elaborates: “This is called ‘one can work with two, two can work with three, three can also work with two.’ You can let go here.” He then instructs the student at Point 1 to move towards Point 2, adding, “One can also work with [two]. You can come here.”

|

Master Chen concludes: “These are the relationship combinations within your [Taiji movements], [such as] in this [first section in the drawing of the Positive Circle] here [‘In with Elbow’].”

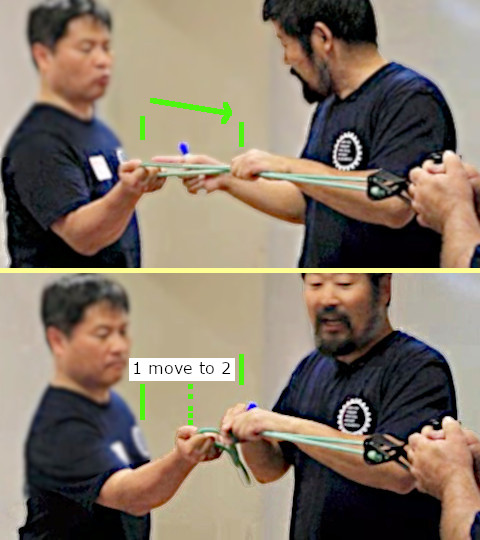

Master Chen then added, “There is one thing that cannot be done: this here [Point 3], while I remain here [holding on Point 2 stationary], must not go there [towards Point 1].” This concept is illustrated in Figure 63. He instructed his students to demonstrate the idea, saying, “You go [and move and touch Point 1]. You see [the result is that] everything [has] collapsed—there is no structure.” Once Point 1 and Point 3 converge, the original linear framework disintegrates. |

|

Master Chen then demonstrates the concept through a physical movement. He says, “That collapsed move—I’ll show you.” He proceeds to bend over, stating, “[Lowering your head and bending over is a] collapsed [of your structure]. Whenever you do this [lowering your head], you have no power.”

As an alternative, Master Chen describes the proper Taiji movement. He explains, “When you are here [at a proper stance], you can sink from here to here [open the front kua]. You can push the foot up to here [into the kua]. But you cannot do this move [lower the head].”

Master Chen reminds his students, “In Taiji—and in all martial arts—[there is a common Chinese adage.] It means, ‘Lower your head and jut out your buttocks. Show that your teacher did not teach you.’ If you’ve been doing it [the action of lowering your head] for thirty years…”

He illustrates this point with an improper movement and continues, “It means your teacher went to sleep while you were practicing the form. If someone was watching, you would never be allowed to do this [lowering your head] here.”

|

Master Chen then contrasts the incorrect posture with the proper Taiji technique, using the Positive Circle. He explains, “When you perform this [‘In With Elbow’] here, this [action] is three [Finger] working with two [elbow].”

He then demonstrates an improper variation: “You do this.” In this version, the fingers drop downward. He observes, “This [incorrect action] is three [the finger] working with one [the front foot].” The front foot is considered ‘One’ because it serves as an anchor on the ground. The correct and incorrect action is compared in Figure 64. |

He concludes firmly, “When three works with one, the structure collapses.”

Master Chen revisits a previous anecdote addressing the false attribution of Faijin to his movement. “This is the story of people saying that [my illustrated action] wasn’t a good Faijin. [But] it wasn’t Faijin—I was demonstrating the [1-2-3] relationship.”

To clarify the power of this 1-2-3 relationship, he uses a bifolding door analogy. “When you go home and see a bifolding door, it’s like that [a physical representation of the 1-2-3 relationship] all the time. With a bifolding door, you pull this [the middle, Point 2] and the two ends [of the door] come in, but the two ends never move in [by] themselves. So, you understand?”

|

He then connects this concept to a Practical Method exercise, describing how level changes occur: “So if you want this [the Banhui] to be lower, you pull this [the rear kua]. But it’s not like this [bowing your head to change the level].” He emphasizes, “This is another very, very important point of the Practical Method. You never lower your head.”

Master Chen then broadens the concept of “head.” Pointing to the finger on his leading hand, |

|

he begins, “Your finger here is the head. On your body, we say there are five heads: two hands, two feet, one head. These are the five heads, meaning the five extremities.”

He illustrates this idea using the ready position of the Positive Circle: “When you are here [at the ready stance], you never go like this [bend your fingers or wrist]. Once you do this [bend your fingers or wrist], you’ve already collapsed.”

To emphasize the significance, Master Chen uses a physical analogy: “Nobody is going to walk on that bridge if the two anchors are lost. Who is going to walk on that bridge [with no anchors]?”

Returning to Positive Circle movements, he continues: “So whatever happens, you can do these moves [such as ‘In with Elbow’ or ‘Out with Hand’]. Can you see here [in those moves]? There is [both] inward tension [and] outward tension. But [when] you do this [relax the fingers or wrist], it [the basic structure has] collapsed. So you cannot collapse [when performing proper Taiji moves].”

“So these are the rules of the three rings of Taiji,” Master Chen explains as he uses the second movement, ‘Turn with Waist,’ to reinforce the importance of the 1-2-3 relationship. “Now you see why we do it [‘Turn with Waist’] like this [without pushing the chest forward] here. Why? Because this movement [of the chest] causes these two [Point 1: the front hand and Point 3: the rear leg] to collapse.”

He continues, “Whenever you move the inside [Two], [the normal reaction is that] the One and the Three will try to see each other. [The correct] One and Three relationship is [term] ‘getting away.’ [One and Three should] Never try to see each other.”

To illustrate this, Master Chen invites a student to push his leading hand. “So if you push towards me… I’ve got no power,” he says, allowing his leading hand to collapse. Then he responds using proper Taiji technique and explains, “But when you do that [pushing onto my hand], I want to do this [perform the technique of ‘In with Elbow’]. Can you see when this [elbow] goes in here [my body]? You cannot push anymore. You feel the difference? As soon as you push, I stick this [my elbow] here [into my body]. Now you see the circle?”

He cautions, “Do not do this here [drop the hand]. When this [lead] hand aims toward the foot, [there is] no more power. You [the structure that you have built has] collapsed.”

He concludes by emphasizing the integrity of form: “So the inward move is like this [like the move ‘In with Elbow’]. Can you see? It [the structure has] become small, but it [the hand] never becomes like this [dropping to draw an imaginary circle]. You can be small, but you cannot change structure.”

|

Master Chen highlights the concept of scale invariance by referencing the Mercedes-Benz logo. “The Mercedes-Benz sign there—you want it to be bigger.” He draws a larger version of the symbol. “It just becomes like this.” Then, drawing a smaller version, he adds, “You want it to be smaller? It’s smaller.”

He concludes, “This kind of transformation on the body is extremely difficult to achieve. It requires very careful and patient training of the circle.” |

Master Chen then illustrates the idea through the movements of the Positive Circle. Beginning with ‘In with Elbow,’ he describes, “Can you see it became smaller? All the limbs remain the same, but everything shrinks inward. Everything goes towards here [the Dantian].”

In the third move, ‘Out with Hand,’ he explains, “Everything opens up. [The structure is bigger.]”

He contrasts this with conventional movement: “Otherwise, can you see everything is wobbly? You see that now?”

The session progressed with the repeated intonation of the phrase, “In with the elbow, turn with the waist, out with the hand,” as students diligently executed the Positive Circle technique. Master Chen then circulated throughout the room, offering targeted corrections and refined guidance to ensure precision in their movements

Correction #1

In the third movement, “Out with the hand,” the hand must not be reversed. One student exhibited a tendency to relax and allow the hand to drop during this phase. The corrective instruction is to maintain tension and extend along a 45-degree trajectory as the hand reaches forward.

Correction #2

Master Chen offered a correction to his student, stating, “In the first movement, do not move the head. Simply draw the elbow toward the Dantian.” He then stepped in to maintain full-body contact with the student, emphasizing tactile feedback.

As he applied pressure, Master Chen instructed, “When I push you, rotate backwards.” With this guidance, the student was able to perform the second movement, Turn with the Waist, more effectively.

Continuing the correction, Master Chen remarked, “The third movement—Out with the Hand—requires full-body extension.” Due to the close contact between Master Chen’s body and the student’s torso and arm, the student’s instinctive reaction was to exert force and push against him.

Master Chen immediately issued a refinement: “Don’t push—stretch.” In response, the student adjusted by reaching across Master Chen’s body rather than resisting it.

Additional instruction followed: “Open the Dantian, so that nothing feels caught.” He reiterated the essential principle—“There is no push, only stretch.”

Correction #3

| Master Chen observed, “On the third movement, you retreated.” He advised that both the Dantian and the kua must be opened. To illustrate this principle, he had his student place a hand on his waist, creating a physical reference point. He clarified that rotating the waist during the Out with the Hand movement was incorrect. Instead, he demonstrated the proper technique by caving in the chest and opening the kua—emphasizing this as the correct action. |

|

He reminded his student: “It’s a stretch. [You must] open [the inside.]” He acknowledged the difficulty of this concept, explaining: “This open [action] is very difficult. Your stomach—people call it the Dantian. Let’s just say ‘stomach’ is just for locating the area.It has to be like a balloon. [It has to be able to expand and contract as needed.]”

This sequence of corrections is depicted in Figure 67, where green lines highlight the appropriate body alignment for accurate execution.

Correction #4

Master Chen instructed a student, “No movement is permitted. However, at this stage—because the technique is quite difficult—you may move slightly. Later, once the fundamentals are in place, you will remain still.” He added, “At this point, I’m observing for major errors. If it’s not a significant one, it’s acceptable.

Correction #5

|

Master Chen addressed the student: “I’ll show you why [you have the error of moving too much]. I lightly touch you—then you perform your movement—and I follow you. As you can see, you have no power [and so] you move yourself [away from me], right?”

He continued, “The test for the correctness of movement is like building a table. When your movement is accurate, you compress the table inward. But when the movement is wrong, |

you bounce yourself backward. There is no need for confrontation—it’s simply a matter of structural error.”

Demonstrating further, Master Chen pointed out, “Look—see, you did this [bend your waist]. If there’s resistance, you’re going to fall. But if you do this [tuck in your tail bone], you remain stable.”

He concluded with a broader principle: “Energy is like electricity. But unlike electricity, we incorporate movement.”

殊途同归

|

「天下同歸而殊塗,一致而百慮。」

“All under Heaven return to the same end by different paths, and reach unity through a hundred thoughts.” 《易經.繫辭下》 |

Neither Opening Nor Closing: From Stance to Stillness

In the Practical Method, the phrase “不啟不閉” is used to describe the foundational requirements of a basic stance. Physically, this stance represents a condition of “Half-on, Half-off”—only the centerline is engaged, yet there’s no committed direction toward left or right, forward or backward. It’s a stance of readiness without bias, embodying balance without intention.

On a deeper level, “不啟不閉” resonates with ideas found in Daoist and Zen Buddhist texts, where it denotes a state of non-duality, pure awareness, and spontaneous being. It’s not about doing, but being—allowing things to unfold naturally without interference.

This concept is beautifully illustrated by Chinese Chan master Shitou Xiqian (石頭希遷; 700–790) in his seminal poem “Identity of Relative and Absolute” (參同契), where he writes:

“Grasping things is surely delusion;

according with sameness is still not enlightenment.”

门门一切境,回互不回互。回而更相涉,不尔依位住。

Here, Shitou explores how sensory experiences both interact and remain distinct, reflecting the same balance of tension and stillness seen in the Practical Method’s physical form.

A parallel teaching can be found in Confucian philosophy, specifically in The Analects of Confucius (論語·述而), which advises:

“If the student is not driven to understand, do not instruct;

if they cannot express themselves, do not explain.

If they cannot infer the whole from a part, do not repeat.”

不憤不啟,不悱不發,舉一隅不以三隅反,則不復也。

Here, too, we see the idea of non-forcing—a respect for timing, readiness, and natural development, whether in learning or movement.

From physical alignment to philosophical insight, this concept carries layers of meaning, each more revealing than the last. If it were an onion, it wouldn’t just make you cry, it might just make you enlightened.

Measures of a man?

In Taiji, form follows function but function is shaped by proportion. The concept of the “seven-inch knife” is one such measure. It’s defined as the line extending from the base of the little finger, passing toward the head of the ulna, and continuing three inches along the forearm. With the average adult male hand measuring about 7.6 inches long and 3.5 inches wide, this form becomes a natural anatomical extension—not just a tool of offense or defense, but a symbol of biomechanical alignment.

Viewed another way, the “seven-inch knife” is the stabilized wrist, anchored by the opposite hand. It embodies the convergence of awareness, structure, and purpose—subtle, yet fundamental.

Similarly, the “one-third rule” in Chen Style Taijiquan is grounded in biomechanics. The human tibia-to-femur ratio is approximately 1:1.28, meaning the femur is about 28% longer. The tibia-to-pelvis ratio sits between 1.2 and 1.4, echoing a universal geometry within the body. These ratios aren’t just academic—they inform movement, leverage, and structure.

Other Taiji principles also reveal this anatomical intelligence. The “Three Rings” is not mystical: the vertebrae, shoulder, and kua form a shared axis—an expression of centerline integrity. Joints like the elbow and knee must harmonize, functioning as biomechanical partners.

Even the coordination between arm and leg length matters. Proportional limbs help maintain a stable center of mass, improve gait mechanics, enhance force generation, and support neurological rhythm. Your build doesn’t just define how you stand—it shapes how you move, respond, and refine.

In Taiji, there is no excess. Every inch speaks. Every angle answers. From wrist alignment to pelvic ratios, from three rings to coordinated joints, these are not just rules of form—they are measures of a man.

Taiji Rocks

The Rule of Threes is a fundamental pillar in Taijiquan, guiding structural alignment and internal logic. At one point, Master Chen spoke with a geologist who observed that this triadic framework also appears in geological science. In geology, rocks subjected to deformation are analyzed using three principal stress axes: σ₁ (maximum stress), σ₂ (intermediate stress), and σ₃ (minimum stress). Likewise, fault structures are categorized into three types—normal, reverse, and strike-slip—while folds fall into anticline, syncline, or monocline. Geologists also describe rock deformation through three primary modes: translation (displacement through space), rotation (change in orientation), and distortion (change in shape or volume).

The parallels between martial theory and geological classification are striking. Yet rather than pursuing metaphysical interpretations, Master Chen offers no speculation. He reminds us that his aim is not to uncover cosmic truths, but to uphold and transmit a traditional art. Taiji, for him, remains a discipline of refinement through practice—one rooted in the body, not in abstraction.

Whether these overlapping triads are coincidence or reflection remains an open question. For Master Chen, it is enough that Taijiquan stands on its own terms, patiently unfolding with each movement, each breath, and each generation.

Circle are triangles?

| Triangles are the simplest geometric shape capable of supporting and interacting with the structure of a circle. In an intriguing twist of geometry, rotating certain triangular configurations can even form a wheel. One such configuration is the Reuleaux triangle. A beautifully curved and counterintuitive shape that rolls like a circle despite being distinctly non-circular. |

|

Although triangles don’t form the foundation of a circle in the strictest geometric sense, they play a vital role in understanding the circle’s mathematical properties. One of the most profound connections lies in trigonometry, which, quite literally, is the study of triangles. The sine, cosine, and tangent functions are deeply rooted in the unit circle, a circle with radius 1 centered at the origin of a coordinate plane. Every point on this circle corresponds to a specific angle in a right triangle, making triangles indispensable for analyzing circular motion and periodic behavior.

Triangles also feature prominently in circle construction and geometry. A triangle can be inscribed within a circle such that each vertex touches the circle’s boundary, or conversely, a circle can be circumscribed around a triangle, passing through all three vertices.

Furthermore, one can estimate the area of a circle using triangles, a method dating back to ancient geometry. By dividing the circle into numerous narrow, pointed triangles radiating from its center, the shape begins to resemble a polygon. As the number of triangles increases, the polygon more closely approximates a true circle, and the total area can be derived with remarkable accuracy. This technique foreshadows the development of calculus and the concept of limits.

Did you get a Mercedes-Benz?

The Mercedes-Benz logo, with its sleek three-pointed star enclosed in a circle, represents the company’s drive toward universal motorization. Each point signifies a distinct domain: land, sea, and air, which Mercedes-Benz aspired to master through its advanced engines. The emblem traces back to a symbol used by Gottlieb Daimler on family postcards and was officially adopted in 1909. Following the merger of Daimler and Benz in 1926, the star was combined with Benz’s laurel wreath, forming the iconic badge recognized worldwide today.

Interestingly, Daimler’s design also echoes a deeper Taiji philosophy. As Master Chen insightfully noted, the brand’s continued pursuit of luxury, innovation, and engineering excellence remains true to both its mechanical and metaphysical roots.

Scale Invariance

Scale invariance is a fascinating concept in physics and mathematics, describing systems or patterns that remain fundamentally unchanged when their size is scaled up or down. This means that the laws governing these systems or the structures themselves appear identical regardless of the level of magnification. In physics, scale invariance is prominently observed near critical points during phase transitions—such as the boiling of water or the magnetization of materials—where fluctuations occur across all length scales. In mathematics, it manifests in functions or curves that retain their form under rescaling, like homogeneous functions. Closely related is the idea of self-similarity, where parts of a system resemble the whole, a property beautifully illustrated by fractals.

|

Fractals are intricate geometric shapes generated by simple iterative rules, yet they produce infinitely complex and detailed structures. Physical examples of scale invariance and fractals include the branching patterns of lightning, the ruggedness of coastlines, the distribution of galaxies in the universe, and the structure of river networks. Even turbulence in fluid dynamics exhibits fractal-like behavior, with eddies nested within larger eddies across scales. These examples highlight how nature often organizes itself in scale-invariant ways, revealing deep connections between simplicity and complexity. |

One might even ask whether Taiji, with its flowing movements and dynamic balance of opposites, can be interpreted as a form of scale-invariant expression. Echoing this sentiment, the wise words of Jedi Master Yoda resonate with clarity: “ Size matters not. ”

Four Tales of Misunderstanding

A physicist rises from his couch, wanders the city for three hours, then collapses back into the same spot. He sighs: “I did no work today.” The couch, unmoved, agrees.

A man spins the merry-go-round too fast. A little girl flies off, lands softly in the grass.

She lies there and stares at the sky, bewildered. Her father rushes over and says, “You fell because of centrifugal force.” She blinks, stares at him with disbelief, then runs to her physicist mother yelling, “Dad is a Liar!”

A clock hand begins at midnight. Now it points to noon. Did it move?

Before bed, a man said to his AI assistant, “Turn off the light.”

The AI asked,“Are you sure?”

Annoyed, the man snapped, “Close that light.”

Morning came.The room was still bright.

He shouted,“Why didn’t you do it?”

The AI replied,“It’s impossible.”

Where is the major malfunction?

Sometimes reality seems ridiculous. Sometimes it’s just a language problem. And sometimes… it hints at a deeper truth.

Epilogue

The screen dims—its neon pulse swallowed by the flick of a switch. Silence unfurls slowly, like smoke from extinguished incense; the teacher’s voice dissolved into air, another lecture evaporating into memory.

Taiji dwells in all things. It is subtle as mist and constant as breath. Its principles govern the turning of stars, the folding of petals, and the tide of seasons. When the heart is shut and the mind is restless, its presence fades into shadow. Unseen and unheard, its harmony slips into silence. It moves through heaven and earth, yet vanishes when understanding falters. It is everywhere, and it is nowhere.

In a quiet corner where light drapes gently over worn stone, a child begins to recite a poem by Lu You (陆游; 1125–1210). Her voice is steady, tender yet unwavering, each syllable lifted with quiet devotion. The words unfold like ink drawn slowly into silk, deliberate and patient, shaped not by habit but by conviction.

Her voice rises just enough to stir the quiet around her. Not dramatic, not bold, just clear and tender, as if she’s tasting each thought for the first time. Her brow furrows slightly; not in strain, but in pursuit.

The final line leaves her lips with a gentle exhale. |

|

|

Laughter drifts through the crowd like wind weaving through tall grass, light and restless. A loose circle of onlookers gathers around a solitary figure with arms extended, keys to a gleaming Mercedes-Benz glinting softly in his hand. He is not selling. He is not boasting. He simply offers. No words accompany the gesture. Only the quiet breath of waiting. Eyes shift toward him, some bemused, others cautious. Smiles rest at the corners of mouths like folded fans, waiting to open if the moment reveals trickery or truth. No one moves. |

The keys catch the light like fire held against the sky, radiant but strangely out of place. They remain suspended, and he remains still. Many hesitate, wrapped in doubt. A few steps forward, not in certainty, but guided by a spirit open to possibility. What escapes the notice of the crowd unveils itself to those who dare to risk it all for the promise of something greater.