|

As the Christmas season approached, Hong Kong shimmered under dazzling festive lights, setting the perfect backdrop for a year ending workshop led by K.T. Lin and Nicholas Fung (馮嘉傑) from the Hong Kong Chen Style Taiji Practical Method (香港陳式太極實用拳法). On a pleasantly mild weekend, more than thirty dedicated practitioners from Hong Kong, Mainland China, the United States, and Canada gathered to train with Master Chen Zhonghua.

A special appreciation goes to Tim Duering and Hán Ruì (韩瑞), who traveled from Daqingshan to support the workshop. Over two transformative days, Master Chen guided participants through the core principles of the Practical Method, including foundational techniques, movement dynamics, and Yilu. Beyond the fundamentals, he also explored the deeper theory of Chen Taijiquan, offering hands-on applications and insights into the intricacies of push-hands training. |

In the beginning

Wén (文) and Wu (武)

|

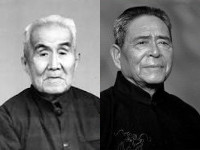

We all begin our Taiji journey with preconceived notions about the nature of the art and the demands of training. Chen Fake (陳發科; 1887–1957) famously remarked, “Learning martial arts (武) is even more difficult than learning literature (文).” Hong Junsheng (洪均生; 1956–1996) interpreted this to mean that true training yields tangible physical results. To underscore this principle, Master Hong introduced the term Practical (实用) to describe his training system.

Master Chen Zhonghua (陈中华; b. 1961) trained under both Master Hong Junsheng and Master Feng Zhiqiang (馮志強), refining his mastery of Taijiquan while also studying linguistics at the University of Regina, Canada. |

He has played a pivotal role in bridging traditional Chinese training methods with modern Western perspectives, highlighting the subtle yet significant differences between Eastern and Western approaches.

In his workshops, participants delve into the study of literature (文) as a pathway to rediscover the essence of martial arts (武), emphasizing the deep intellectual and physical connection within Taijiquan practice.

The Way? (道)

|

Master Chen consistently emphasizes the profound Taoist influences essential to understanding Chen Taiji. At the heart of Taoist philosophy lies the Daodejing (道德经), a foundational text dating back to the 6th century BC, written by the sage Laozi (老子). It serves as both the beginning and the culmination of Taoist thought, shaping perspectives on balance, movement, and the flow of energy.

The Daodejing opens in Chinese with the following passage:

|

This text has been translated into English over 250 times, with each translator inevitably infusing their own interpretation or perspective into its brief yet profound wording in an effort to convey meaning.

However, as Master Chen highlights in his discussion on the challenges of “Learning a new language”, this could result in confusion or even distortion. Using a more literal translation :

“A way that can be followed is not the way.

A name that can be named is not the name.”

|

To grasp the meaning of these words and sentences, they must be understood within the framework of Taoism—its systems and traditions. As Master Chen reminds his students, attempting to interpret them through another lens, such as logic, can lead to misunderstanding. If a sentence seems illogical, one must be willing to set logic aside, even if past experiences and achievements are deeply rooted in rational thought.

Embracing this perspective marks a crucial turning point in Chinese tradition—entering the door (入门)—unlocking the deeper mysteries of the art. |

|

Bruce Lee encapsulated this transformative experience as entering the dragon, a journey that promises an exhilarating ride. This shift in understanding is the beginning of the literature (文) of Taiji, a key that ultimately leads to rediscovering the martial (武) essence of the quan.

Health (健康)?

Many people embark on their Taijiquan journey not in pursuit of martial prowess, but with a focus on health and well-being. Master Chen emphasizes that while Chen-style Taijiquan was originally developed as a martial art, its health benefits emerged as a fortunate and welcome byproduct.

|

The origins of Taijiquan trace back to Chen Wangting (陈王庭, 1580–1660) of Chenjiagou (Chen Village, 陳家溝). For nearly two centuries, each generation produced exceptional martial artists, yet their practice remained rooted within Chen Village. As farmers, their primary livelihood was agriculture, but their martial skills played a crucial role in defending their community.

In the 1800s, this training system began to spread beyond Chenjiagou, eventually reaching the imperial capital, Beijing. In this cosmopolitan setting, the principles of self-preservation differed from those of the rural countryside. Over time, the five major family styles—Chen, Yang, Wu, Wu (Hao), and Sun (陳, 楊, 武, 吳, 孫)—emerged, each developing its own traditions and insights. |

|

|

Masters representing these styles built their reputations on martial prowess, with some practitioners preserving their skills well into old age despite diminishing physical strength.

In the modern era, esteemed Chen-style practitioners Master Hong Junsheng reached the age of ninety, while Master Feng Zhiqiang lived to eighty-four—both maintaining their martial skill and vitality well into their later years. As Chinese society evolved, there was a noticeable shift in focus from the martial aspects of Taijiquan to its literary and philosophical dimensions. Over time, the practice became more widely recognized for its benefits to health and longevity, rather than as a system of self-defense. |

In the West, this trend has been even more pronounced, with some choosing to emphasize Taijiquan solely for its health benefits while neglecting its martial origins. This approach, as the saying goes, is akin to putting the cart before the horse (本末倒置), overlooking the fundamental purpose upon which the system was originally built.

Direct transmission

| In a previous workshop, I remarked that to “find a good teacher, first look to his students.” In this session, Master Chen highlights another crucial reason why this principle matters. Unlike literature, martial arts require direct, hands-on experience. In today’s multimedia age, there is no shortage of books and videos detailing martial arts techniques, but as Chen Fake and Hong Junsheng remind us, Chen Taijiquan is a physical phenomenon—one that must be felt and practiced to be truly understood. |

|

Master Chen’s workshop offers a rare and invaluable opportunity—one that cannot be fully captured through secondhand descriptions , which remain mere shadows of the actual experience. The significance of direct transmission extends beyond Chen Taijiquan; it is a fundamental principle in most traditional Chinese martial arts and Chan (禪) Buddhism.

In Chan Buddhism, the concept of special transmission beyond written teachings (不立文字、教外別傳) emphasizes the necessity of direct contact with an enlightened master. While a teacher’s words may guide you to the threshold, it is their physical presence that allows you to truly step through the door and immerse yourself in the deeper mysteries of the art.

Some where along the way

|

Capturing the brilliance of Master Chen, Tim Duering, and Hán Ruì’s techniques is beyond my ability to fully articulate. The workshop was filled with unforgettable moments—the effortless precision of Master Chen’s applications, the masterful push-hands techniques of Hán Ruì, and the depth of experience that Tim Duering brought to every exchange. Fortunately, I am certain there will be many videos from this event, allowing others to witness and study these remarkable demonstrations firsthand. |

While I may not be able to fully capture the intricacies of their techniques, I can share some of the most compelling soundbites that encapsulate the core principles Master Chen discussed.

It is truly fortunate that he consistently reiterates these concepts in both Chinese and English, ensuring that no meaning is lost in translation.

To a casual observer, these sentences may seem like scattered words, but to students of the Practical Method, they are strands woven into the rich tapestry of the quan—each one a vital thread that connects theory to practice. As Master Chen put it:

Master Chen Said:

|

|

The cycle begins again

|

A parting reflection for those embarking on the long and demanding journey toward Taiji enlightenment. In moments of solitude between workshops, let the words of Wang Zhihuan (王之渙, 688–742) offer inspiration and contemplation:

|

|

Which translates as:

|

As 2016—the Year of the Monkey—approaches, Master Chen prepares once again to embark on a global journey, sharing his invaluable hands-on transmission of Chen-style Taiji. With each foundation laid, every Yilu practiced, and every push-hand exchanged, a new generation of Taiji enthusiasts gains a glimpse into the distant past, forging a renewed future for this ancient art.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Great wisdoms from Master Chen ZhongHua and how fortunate to be able to

learn from him !

I love Ming’s article. It is so well written to convey Master Chen’s messages.

Great piece. I enjoyed reading it. Thank you.