|

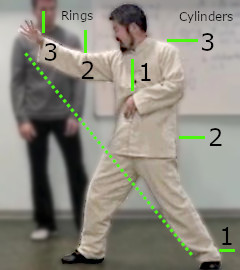

The practical application of the Three Rings Theory dictates that effective force generation relies entirely on the correct mediated connection (R1 ↔ R2 ↔ R3), while the forbidden relationship (R3 → R1) is a structural weakness. Master Chen’s demonstrations show that the Middle Ring (R2)—the elbow or major joint—is the indispensable kinetic bridge, neutralizing strong grips and anchoring the body during power transmission. This theory validates that true structural integrity comes not from muscular resistance, but from establishing a full-body structural stretch which generates a multiplicative 45-degree power line. |

| Furthermore, the sequence of ring engagement determines the nature of the power: a fast R2 → R3 sequence yields ‘Quick‘ (hammer-like) power, while the full R3 → R2 → R1 sequence establishes the ‘Heavy‘ (pillar-like) defense, proving that mastery lies in precise, integrated action rather than brute strength. | |

| (This is Part 3 of a five part article based on the Three Rings of Tai Chi filmed in 2010, Edmonton, Canada.) |

|

|

Part 3

Part 4, Part 5

|

Part 3

Applications

Master Chen began the technical lecture by telling his student, “Now I just come here, I’ll make some moves with you to demonstrate [the implications of the Three Rings Theory.]”

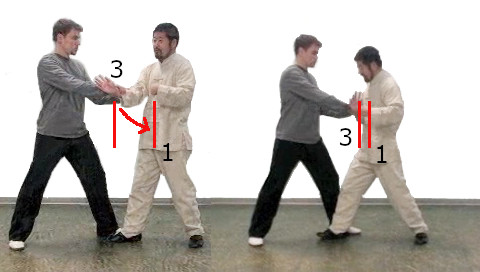

Example 1: Comparing Forbidden (R3 → R1) vs. Correct (R3 → R2 → R1) Power

The demonstration started with the student gripping Master Chen’s extended right arm at the wrist and close to the elbow.

The Incorrect Action: R1 to R3

|

Master Chen described the first part of the demonstration, focusing on the result of an incorrect action. He stated, “When you touch me [by holding my right arm], you can feel when I [perform an incorrect action], if the One [R1, the Core] comes to Three [R3, the Hand/Wrist] here, now you push, you feel [the result of this incorrect relationship].” |

He then asked the student to feel the consequence: “Can you feel that you have the advantage?” The student was able to successfully push Master Chen back, indicating a structural weakness.

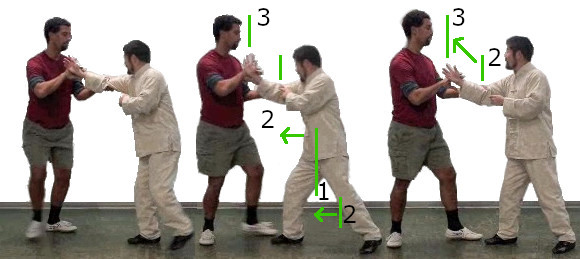

The Correct Action: R2 to R3, then R1 to R2

|

Master Chen then reset his posture. This time, he performed the action according to the Three Ring Theory. He aligned his right elbow (R2) toward the right hand (R3) and maintained this alignment in response to the student’s push.

He explained the first phase of the correct action: “But if here. Two comes to Three [meaning pushing the elbow onto the hand].” |

|

Master Chen followed this action by moving One [the Core, R1] towards Two [the elbow, R2]. The result was immediate and decisive: The student is forced to move back.

Master Chen then explained the improved structure and power: “You don’t have the advantage. Can you feel [the correct action and understand what] I explained? I became stronger. I’ve got two energies.”

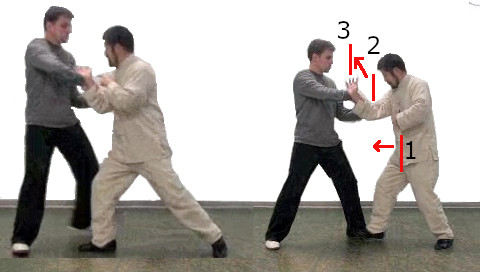

Example 2: Mastering the Middle Ring

Master Chen provided another example, once again letting his student hold his leading right arm by the wrist (R3) and close to the elbow (R2).

Dealing with a Strong Grip R2 to R3

Master Chen outlined the starting position: “Now we do a simple one. [Initially,] You got me here [with both of your hand]. So this [grip on my wrist] is a strong [hold].”

He then demonstrated the familiar correct action: “So I put the Two [elbow, R2] onto Three [hand, R3]. Can you see I aimed Two onto Three?”

When the grip is too strong counter with R2 to R1

|

Master Chen allowed his student to hold his wrist with even more power to set up the next scenario. He explained the student’s initial advantage: “So now [this grip on my wrist,] you are stronger than me. This [grip on the wrist] is too strong. Push it, you see [you can push me back].”

Master Chen then described his strategy for neutralizing this superior force: |

|

He concluded this part by summarizing the theoretical completeness: “Now [in theory,] that’s all nine [possible combination of relationships].” |

|

The Principle of the Middle Ring (R2)

Master Chen finished by pointing to the acceptable relationships of the Three Ring Theory. He summarized the combined actions: “So I did two [relationships] because One is allowed to go with Two [R1 to R2]. And Three [R3] is also allowed to go with Two [R2].”

He emphasized the significance of the elbow (R2) in this dual action: “So [in this example,] two things happen at the same time. Everything crashes onto this [elbow R2] here. And you are allowed to crash onto it. Why? Because Two [being a joint] has a space in it. Don’t crash onto things that do not have space. So there is a buffer in it [the Middle Ring].”

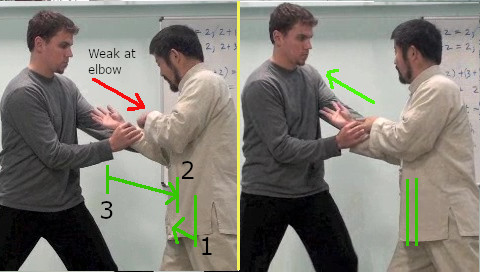

Example 3: Exploiting the Forbidden Link – Using R3 → R1 as a Tactical Weakness

Master Chen began by providing a demonstration with another student. The student was instructed to use a standard two-hand hold on Master Chen’s right arm: one hand gripping the wrist (R3) and the other near the elbow (R2). Master Chen stood in a proper stance to start.

Strategy: Take Advantage of the Forbidden Relationship R3 to R1

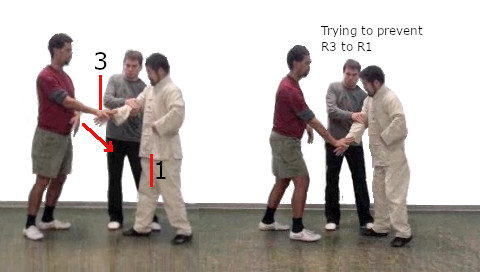

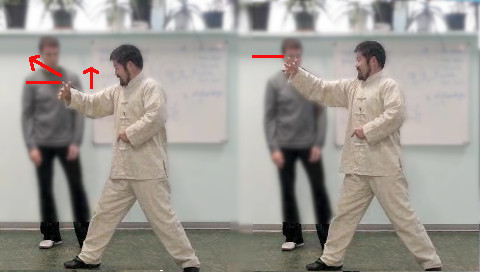

Master Chen initiated the first concept, the Forbidden relationship of R3 (the Outer Circle, the hand/wrist) moving toward R1 (Inner Circle, the dantian or core).

He started with a dramatic movement against the grip on his right to illustrate the concept: “So I’ll go drastic. You can feel. Can you feel I have some ability on you?” The student confirms that he can feel Master Chen’s push against his grip.

|

Master Chen then allowed his student to push his right arm back towards his body, forcing the hand/wrist (R3) close to the core (R1). As soon as this happened, the structural power was lost, and he explained: “But can you feel I don’t have ability on you anymore? Because the hand is, Three is too close to One. So you fight me, you see. It’s very easy [to push me when I exhibit the Forbidden relationship].” |

This demonstrated a critical Tai Chi strategy. He instructed the student on how to exploit this structural weakness: “That’s how, now you keep in mind, every time you feel a movement on my part of Three going into One, you use it. It means you push fast.”

Master Chen guided the student on using this precise strategy, emphasizing the timing and lack of needed strength: “And see here [My hand is moving towards my body]? Don’t use power. As soon as I do this [drop my hand towards my body], [you move forward, I have to move back.] it goes like that. And I can’t reverse it. Because [when R3 to R1, both things does not have any space] that’s a crashing point.”

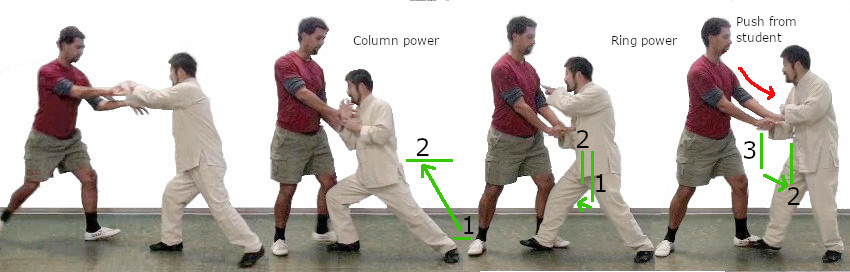

Combinations

Next, Master Chen demonstrated the correct action, which is based on proper Ring relationships, like R2 (the elbow) relating to R3 (the hand/wrist): “But if I do this [an action based on proper relationships R2 to R3], you have to get away.”

|

The student was immediately forced backward. Master Chen then asked for confirmation of the power:”So now you feel this. Strong, right?”

He then combined two relationships to increase the structural integrity and power: “While doing this [initial action of R2 to R3], I add this [relationship R2 rear knee to R1 the core] to it [the initial relationship as well]. Can you see how much stronger?” |

|

A Strong Opponent

Master Chen also explained a defensive variation where he reacts to a stronger opponent holding him. He encouraged the student to hold him very strongly:”So if I feel you are stronger than me [when you are holding me]. Push hard. Yeah, yeah. Very strong.”

|

The correct defensive reaction involves linking the inner Rings to diffuse the incoming force: “So I move myself to link here [using the relationship R3 to R2 and at the same time R1 to R2. You feel that?”

This action stopped the student’s forward progress. Master Chen then finished the technique by reversing the action, using the proper Ring sequence R1 to R2 and R2 to R3: “And then here [I reversed the action by using the relationship, R1 to R2 and R2 to R3. See, the hand is there [in line of my elbow]. So this is the combination.” In addition, there is added power from Cylinder 1 (ground) to Cylinder 2 (knee) and then from the knee to the waist. As a result, the student was moved backwards.

Example 4: Structural Integrity Under Stress – Maintain Power in the Positive Circle

Overcoming External Pressure

Master Chen continued his demonstration to showcase how the Three Rings Theory works under drastic external pressure. “So I’ll do a more drastic [example.] Because … the strength of an action model can often conceal its deficiencies but any model will eventually fail without a solid theoretical foundation..”

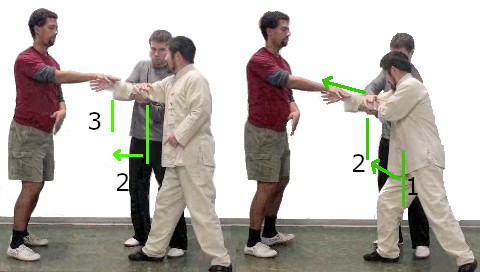

|

He requested two students for this part: one pressed on top of his right hand (R3), and the second uses two hands to held his right elbow (R2). He explained his initial struggle:”I [will] try to [prevent the] link [my hand] to here [dantian].”

He asked the students to apply pressure: “Push me [the right hand] down a little bit. Can you feel I’m trying to [prevent this] link [my hand to the dantian]?” |

| Master Chen visibly struggled, keeping his arm rigid to resist the push toward his core, demonstrating the inefficiency of mere muscular resistance: “You don’t need much power [to push my hand towards my body. Normally, I must struggle to prevent my hand from reaching my core].” |

|

He then offered the solution by applying the Theory of Three Rings: “When that happens [a push of my hand towards my body], I try to link [the push of the hand to] here [the elbow (R2)]. You feel [the difference between active resistance and reacting according the Theory]?”

|

By focusing the incoming energy from the hand (R3) to the elbow (R2), he redirected the force:”[Using the relationship of R3 to R2, when the energy is on the hand, you ] Try to link here [to the elbow]. [If you can achieve that, the] Energy goes out. [The opponent is force back].” |

In this specific example, the second student, who was holding the elbow (R2), provided a stable anchor, allowing Master Chen to establish the R3 to R2 relationship and repel the incoming force. This anchor also allows the combine action of R1 to R2 to increase the power.

Application to the Positive Circle

Master Chen highlighted the importance of this linking concept in a common Tai Chi movement: “Now this is [the same type of relationships we try to establish] when we do the [action of ‘Out with Hand‘ when performing the Positive Circle.”

|

The movement was demonstrated to illustrate the crucial kinematic link between the elbow (R2) and the core/Dantian (R1): “Can you see here [the elbow]? Can you see this here [the Dantian]? [I am] Trying to link here [the elbow R2] to here [the Dantian R1]. Can you see this [elbow] turns [inward] towards here [the dantian. So that the elbow and dantian is inline]?”

Further analysis of the power generation during this specific “Out with Hand” action shows that the rear foot contributes significantly, forming a chain connection with the Dantian and the leading finger. |

|

This kinetic chain can also be understood using the Three Cylinder Model, which posits an axial connection: the feet (Cylinder 1) transfer force to the waist (Cylinder 2), which then transmits to the head (Cylinder 3). The net power output for the action, representing the force of the entire unified body structure, is conceptualized as a 45∘ vector extending from the leading finger to the bracing rear foot.

|

He contrasted this with an incorrect action—just raising the hand—which lacks structural power: “If I [just] do this [raise my hand], there’s no power [in that movement].”

He then explained why techniques can fail and look “unreal” when done incorrectly: “So [in a technique,] if you put [stretch] yourself to the extreme [position], you will feel that it [the technique] won’t work. And that’s why eventually it [Tai Chi techniques] looks unreal.” |

Example 5: Full-Body Stretch – Generating Multiplicative Power

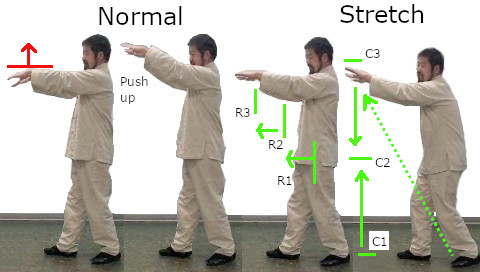

|

Master Chen showed a student the stretch, a technique that physically demonstrates the principles of correct body alignment. These principles are derived from the Three Rings Theory and the Three Cylinder Models, which together represent a Three Dimensional model of the human body. He raised both hands straight to shoulder height, a position of minimal leverage, and allowed the student to press down on his hands: “Because my hand is very far from here [my body. It seem I have no power]. See? All right?” |

He instruct his student. “Apply Pressure [to the top of my hands] you see. It’s very difficult [to resist your pressure].” His hands were forced to bend as he struggled to resist.

| He then applied the full Tai Chi principles, linking the Rings (R2 to R1) and the larger Cylinders (C3 to C2): “When you do this, I link here [elbow R2] to here [Dantian R1]. Here [Head Cylinder 3] to here [Cylinder 2].” With this proper linking, the structural power returned, and the student was easily pushed away.”Can you see? Can you feel the difference?” The key distinction between a typical pushing reaction and the Tai Chi action is subtle, but the outcome is dramatically different. |

|

Instead of pushing up into resistance, the Tai Chi method establishes correct internal pair relationships. This setup creates a full-body stretch that links the front hands directly to the rear feet. When engaging an opponent, this integrated structure generates a multiplicative power that follows a continuous 45-degree power line from the ground, through the body, and into the hands.

Master Chen concluded the lecture by summarizing the essential relationship for generating power: “So the Twos are working with the One. Not One working with the Three. So eventually, this [Three Rings Theory] is how it works.”

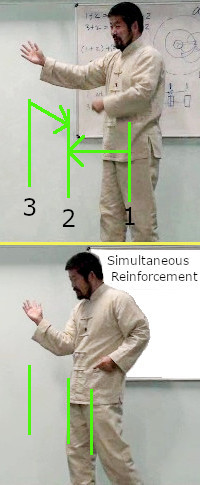

Quick and Heavy: The Direction of the Three Rings

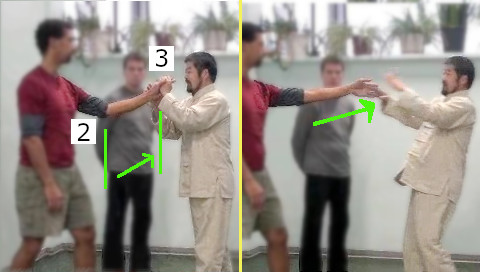

A student asked a key question: “Can you explain the difference between [the relationship] Three plus Two [hand linking to the elbow] and [the converse] Two plus Three [elbow linking to the hand]?” This simple inquiry prompted Master Chen to describe the crucial importance of direction in the relationship of the Three Rings.

Master Chen answered with a demonstration, instructing his student, “You grab me. You push. You see?” The student then grabbed Master Chen’s right hand. Master Chen pointed to his elbow, clarifying the landmarks: “So this[elbow] is Two. And this [wrist where the student is grabbing] is Three.”

The ‘Quick’ Technique: Two to Three

|

With the landmarks defined, Master Chen told his student to initiate an action: “So you push me.” As soon as the student pushed on the hand, he felt a resistance. Master Chen asked, “Can you see my Two is on Three? Can you feel my elbow onto my hand?” He then explained the principle: “So when Two goes to Three, this [in Tai Chi technique] is called ‘Quick‘.” Master Chen then instruct his student to perform the technique. |

The ‘Heavy’ Technique: Three to Two then Two to One

| Master Chen continued the demonstration, this time with the student grabbing the wrist with more strength, which made the previous ‘Quick’ technique seem ineffective. Master Chen instantly transferred the power of the student’s grab from the hand [Three], through the elbow [Two], and then to the core [One]. He described the resulting technique: “Okay? [starting with Three going to Two] And when Two goes to One [in Tai chi technique] is called ‘Heavy‘.” |

|

Then, he told the student to push again: “So now you push.” The student pushed as Master Chen connected the elbow to the body. He asked, “Can you feel that [technique]? Very heavy.”

Master Chen contrasted this with the prior technique, emphasizing its speed and solidity: “But if you go like this [a sudden grab of my wrist with less power]. I quickly go [and put the elbow] in here [to the grabbed wrist]. You feel it’s very quick [response to your grab]. [Even though it appears I have not moved, the technique of establishing that relationship between the elbow and hand,] It has power. Solid power.”

The Pillar and the Hammer Analogy

To differentiate the two techniques, Master Chen used a powerful physical analogy: “So when I use those terms [of ‘Quick’ and ‘Heavy’ They are description of what your opponent experiences. Another way of understanding them is through a physical analogy.] I mean one [technique] is [like being hit by] a hammer, another [technique] is [like crashing into] a pillar.”

|

Master Chen explained how the ‘Heavy‘ technique establishes the pillar: “So if Three [hand] goes to Two [elbow] [then Two (elbow) goes to One (core)], it is [like crashing into] a pillar.” Effectively, by establishing this chained relationship, the opponent is pushing against Master Chen’s entire body structure. |

| He then described the ‘Quick‘ technique that produces the hammer effect: He instructed his student, “If I touch [your leading hand], as soon as I touch [and grab your hand], you push this [R2 elbow]. [This technique requires you to] Relax your body [and] only [focus] here [your forearm]. Push [your elbow] onto here [the hand]. And you see? It [the action] is very quick. You produce a hammer-like power.” |

|

However, he added a crucial caveat for the hammer technique: “But the hammer will not work on a mountain. So you need a larger hammer.” This means if the opponent is very strong, the ‘Quick‘ hammer-like action might not work, necessitating the use of the ‘Heavy‘ pillar technique.

Master Chen concluded the comparison: “So basically, both variations are correct. However, within being correct, there is stronger power and there is quicker power. This illustrates the variation [between the relationship of the Three Rings and the importance of sequence]. This [theoretical principle] here will [often] not work [in real-world applications]. This is only the theory. The practice is not solely based on this.”