|

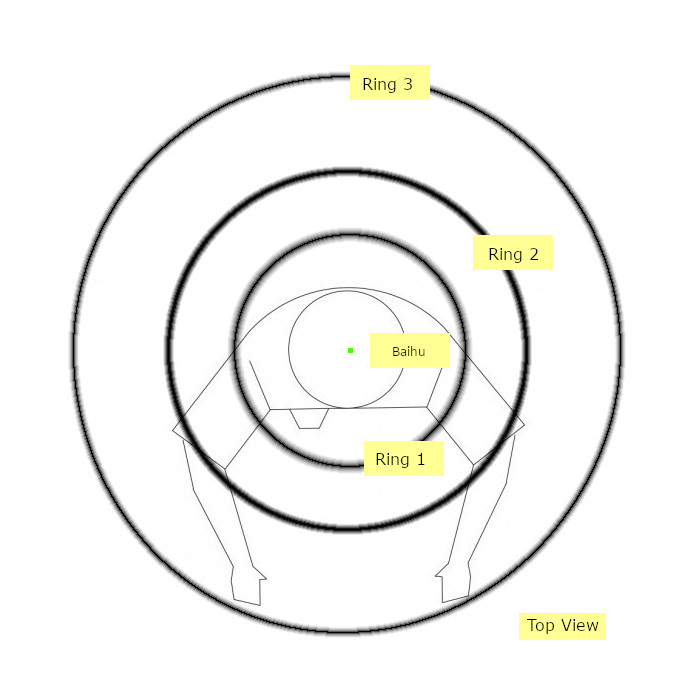

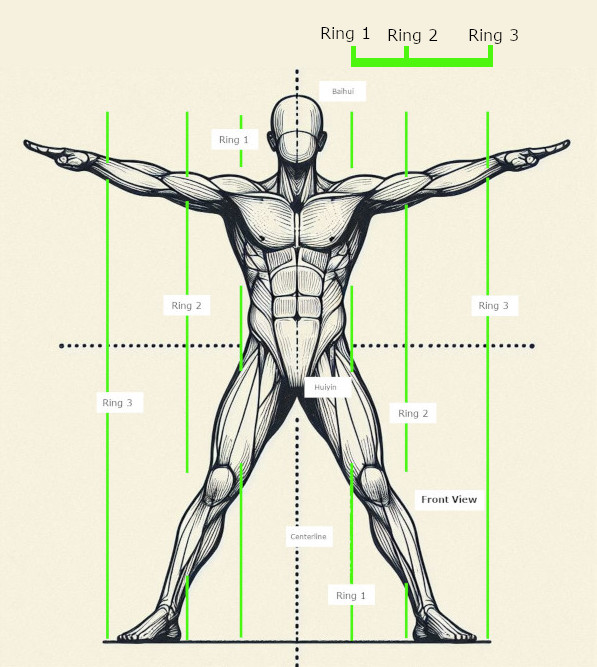

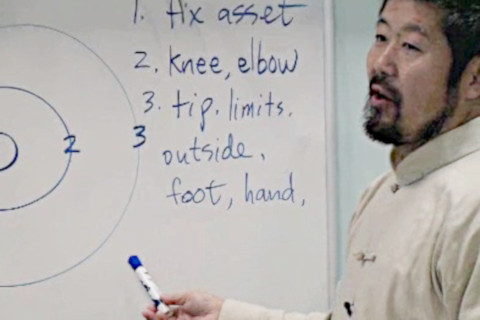

The mechanics of Tai Chi are fundamentally built upon the universal Principle of Three, a concept that not only governs physical structure but also extends to human behavior and operational systems. This principle organizes the body into the Three Rings (太極三環): the stable Ring 1 (内圈/Core), the mediating Ring 2 (中圈/Lever Arm and Major Joints), and the mobile Ring 3 (外圈/Extremities). This mechanical framework is essential for defining structural integrity and efficient power generation in martial arts, establishing Ring 1 as the fixed power source, Ring 2 as the indispensable buffer and kinetic bridge, and Ring 3 as the external application point. |

| Effective force is generated only through the coordinated relationships of adjacent rings, making a direct connection between the Core (R1) and the Extremity (R3) structurally forbidden as it bypasses the necessary leverage of Ring 2. Ultimate power is achieved when all three rings are perfectly and simultaneously integrated, generating a force far greater than the sum of its parts. The core mechanical model is not limited to a simple 2D analysis; it expands into a comprehensive 3D theory of the body and serves as an analogue for general human behavior. The Practical Method of Tai Chi applies this framework through the training of the Positive Circle, which is specifically used to correct deeply ingrained physical and kinetic habits, thereby demonstrating the profound effectiveness of the Three Rings theory in achieving the mastery of integrated action and conduct. | |

| (This is Part 2 of a five part article based on the Three Rings of Tai Chi filmed in 2010, Edmonton, Canada.) |

|

|

Part 2

Part 5

|

Part 2

Transition: From Mechanics to Human Behavior

From Mechanical System to Universal Principle

|

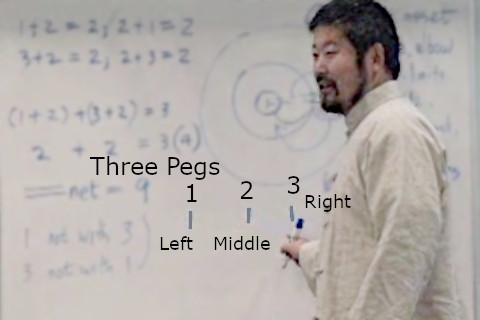

Master Chen begins. “Now I have explained the entire relationships of the Three Rings Theory. [The Rings are two-dimensional constructs.] Yet, the Three Rings Theory is [actually] a three-dimensional model of your body.”

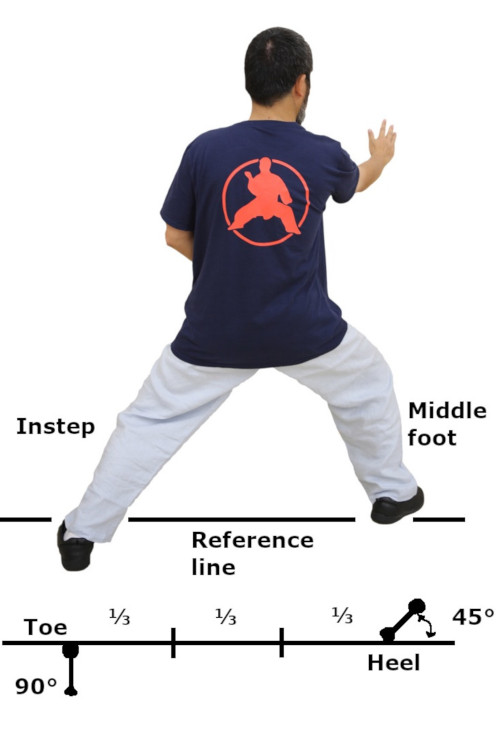

This means the initial representation is a two-dimensional slice of the human body projected onto the transverse plane, with the centerline of the body serving as the center of the innermost ring (R1). A logical extension of this theory into three dimensions is to describe the rings as columns, extending the perimeter of each ring parallel to the central longitudinal axis. |

| Master Chen reviews the basic concepts. “I have my core energy [Ring 1], I have some flexible moving parts [Ring 2], and then I have an end tip [Ring 3]. That’s what my body is; there is no exception. [Normally,] when you are physically looking at me here [from the front or the side,] you are only looking at [a flat] surface. You are looking at what you could call a two-dimensional flat model [specific to the sagittal plane or frontal plane]. From the top [using the projection on the transverse plane,] you can see the workings—the connections of the body [in relation to the frontal and sagittal axes].” |

|

The core of the Three Rings Theory is a complete, simplified mechanical system: we’ve identified four functional relationships necessary to generate effective power and one single, forbidden relationship (R1 ↮ R3). Understanding this mechanical framework—the imperative sequence you must follow (R1 ↔ R2 ↔R3) and the direct link you must not attempt—is crucial for physical efficiency.

The ‘Three Rings Model‘ represents general principles, not just mechanical body mechanics. The basic idea is to describe any process in terms of three states: a beginning (Ring 1), a transition (Ring 2), and a final state (Ring 3). These principles can also be applied to abstract concepts, such as human behavior, demonstrating how these precise structural rules govern your decisions, actions, and capacity for effective change, revealing the theory as a model for a deeper, universal truth.

Master Chen concludes. “So, this is almost everything mechanically about your body. Now, let’s go back again to review. There are so many things you can do, but there is only one thing with the two parts you cannot do. And now, let me relate that back to human behavior.”

The Three Rings System: Correcting the “Candy Jar Syndrome”

Master Chen begins his technical analysis by establishing the core problem: the need to replace natural, yet inefficient, human habits with the structured efficiency of the Three Rings system. “So now let me tell you why it’s like that. I’ll explain it myself and then you can see whether it works. We can use some tests and doing it you see [the applications of these principles.]”

The Conditioning of Habit: The “Candy Jar Syndrome

The difficulty in adopting the Three Rings system lies in fighting our deep-seated human habits. Our natural, untrained behavior gravitates toward the forbidden R1 ↮ R3 relationship. Master Chen refers to this instinctive flaw as the “Candy Jar Syndrome.”

|

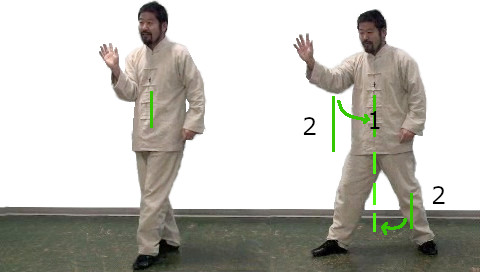

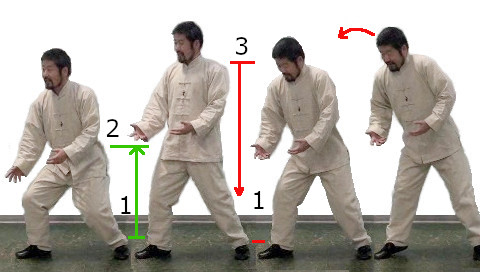

Master Chen demonstrates this instinct starting with the Positive Circle posture: “[At the beginning,] when your hand is here [the right hand out at shoulder level,] Our immediate reaction instinct is to do this.” As he pulls his hand inward, he identifies the compromised relationship: “When you do this [pull your hand into your body]. This [your hand] is Three [R3, the outermost Ring] it wants to come close to One [R1 – the body core. Moving the hand to your body is the Forbidden relationship.]” |

Like a child whose attention is fixed entirely on the candy jar, our human desire focuses 100% on the immediate goal (Ring 3), bypassing the necessary structure (Ring 2).

|

|

Reconditioning and System Adherence

To execute proper Taiji or internal arts, we must undergo a radical reconditioning (重新訓練, Chóngxīn XùnLiàn) of the body and mind. This process is similar to how a society establishes a system to replace primitive, self-centered desires with structured, coordinated effort (e.g., adhering to time for collaboration).

Master Chen emphasizes the necessity of the system: “So things that you don’t like to do must be redrilled into you like the reconditioning of the body… having a system is an indication we want to train you to prepare you to do certain things… if you want to do this [Tai Chi movement following the principles of the Three Rings] then it’s inevitable you have to follow the system. To follow the system you have to train yourself to get away, to recondition yourself from this habit [of following the Forbidden Relationships R1 ↮ R3].”

The Corrective Action: R1 ↔ R2 ↔ R3

|

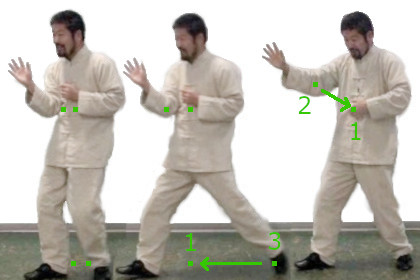

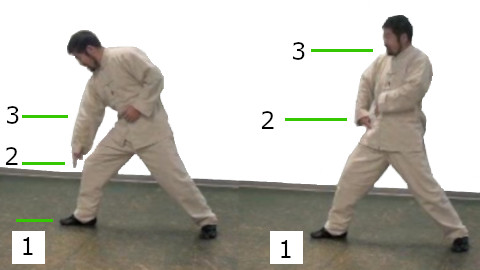

For the initial example of drawing the Positive Circle, the natural—but incorrect—action is for the front hand to drop back toward the body. “so our [Practical Method training corrects this flaw with the action described as ‘In With Elbow‘.]”

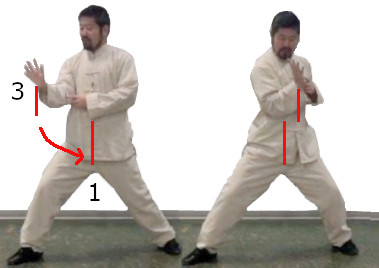

He demonstrates that the hand must not retract alone. Instead, the middle ring is activated first:”Can you see [the correct action for withdrawing the hand towards the body is to first let the] elbow comes in [to the body.] [Using the terminology of the Three Ring Theory], this is number two [R2 – the elbow] can work with number one [R1-the core].” |

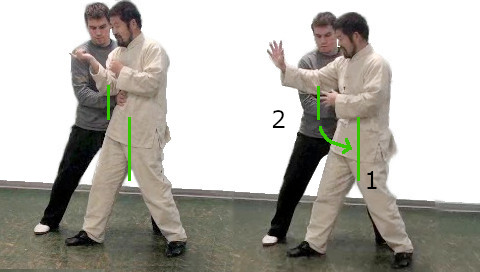

| By adhering to this systematic training, the body is forced to use the correct energetic flow (R1 ↔ R2 ↔ R3). This principle is demonstrated in various applications using the same Positive Circle starting posture, such as when an external force is encountered: the body (R1) moves to support the elbow (R2) which then manages the hand (R3). Master Chen shows: “The elbow is somehow linked to the hand in combat…[when the movement of the elbow is restricted]; So you can do this,” and then steps to eliminate space by pulling his core towards his elbow. |

|

|

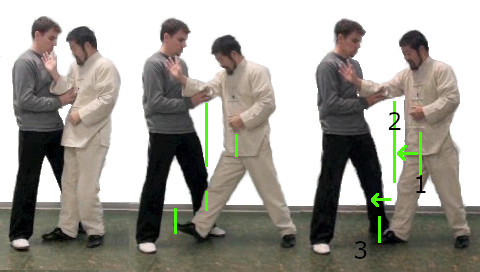

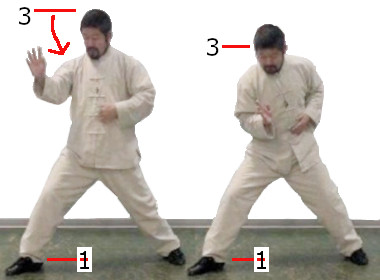

Master Chen continued to demonstrate the practical applications of the Three Ring Theory, explaining that actions based on two distinct relationships can exist and be executed simultaneously. Starting from the initial position, and maintaining the restrictions associated with the forward movement, he executed a synchronized dual action: he moved the front elbow (R2) backwards toward the torso (R1), while concurrently stepping forward by utilizing the relationship between the front knee (R2) and the front feet (R1). This display effectively showcased how two separate R2 → R1 relationships contribute to a single, integrated movement. |

| Master Chen provided another example of a practical application, maintaining the same initial assumptions. To resolve the restrictions of the initial position, he executed two R2 → R1 relationships simultaneously: he brought the core (R1) into the front elbow (R2), and at the same time, brought his rear knee (R2) to the centerline (R1). This demonstration effectively illustrates the three-dimensional application of the Three Ring Theory across different planes of the body. |

|

This systematic training ensures that the body’s energy flows correctly, preparing you to execute higher-level skills.

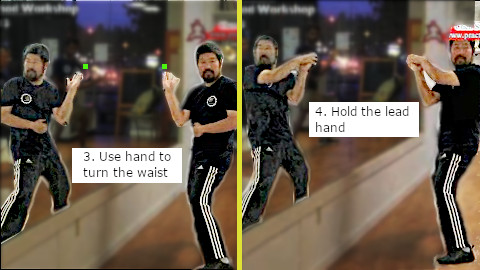

Master Chen continued his practical demonstration of the Three Rings Theory with a student. He set up the scenario by pointing to his right elbow, instructing the student, “If you don’t move this elbow. Grab it [the right front elbow] and hold it [the elbow], don’t make, lock it [in place].” To test the student’s resistance, Master Chen attempted to move the elbow but couldn’t, observing, “You are strong. Can you see I can’t move it [the elbow].”

|

He presented a second example. The student was instructed, “Now if you hold me here [around the dantain].” Master Chen explained the premise: “In fighting for whatever reason, I can’t move forward [because the hand is preventing my body from moving forward.]” To resolve this, he applied the theory in reverse: “I just simply come back here [with the elbow. This is applying the relationship of R2 (elbow) to R1 (core).” This technique in Tai Chi Chuan is called ‘to suck.’ |

| Master Chen then applied the theory, explaining the correct action: “When I do this here [move my body towards the elbow]. This action [as explained by the Three Rings Theory is] one [R1 – the core] coming to two [R2 – the elbow].” This favorable relationship, where the core drives the movement out to the limb, is a foundational Tai Chi application. This technique is called to ‘stick.’ An alternative name for this specific application is ‘Ji,’ one of the Eight Methods of Tai Chi Chuan. |

|

Master Chen then summarized the breadth of these applications: “In Tai Chi there are actions called ‘to suck,’ ‘to stick,’ ‘to swallow,’ ‘to spit‘ and [many other variations.] All those things relate to the method of Three Rings. [Those techniques fundamentally are explained by the relationship principles] which one works with which one and because of that there are orientations and because of that, the energy you produce will feel very different on your opponent’s body.”

The Challenge of Retraining and General Applications

Master Chen emphasized the difficulty of internalizing these mechanics, reminding his student, “So you see how difficult it is to retrain your body to do to do this [move according to the Three Ring Theory] and we are like to do this [move the hand towards the body according to the Forbidden Relationship].” He identified this as a fundamental human challenge: “This [habit of preferring the Forbidden Relationship] is the single most physical handicapped all humans have.” He then expanded the scope, stating, “[Even though, this discussion is] Only in relation to the Tai Chi we want to do but I personally like to believe the Tai Chi system of the body mechanics is not only good for Tai Chi it is also good for everything you do. [That the Three Ring Theory is actually a general principle.]”

Three Cylinder Model

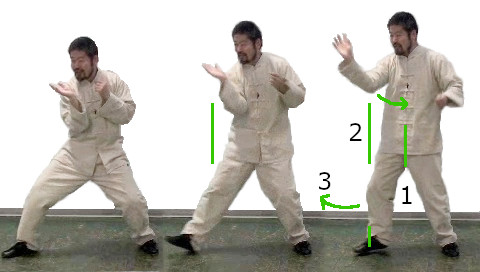

As a general application, Master Chen discussed the example of lifting an object. “Imagine you are going to lift something and I do not really know how the people in the other fields teach you if you want to lift something it’s like this.” Master Chen demonstrated a lift by bending the legs while keeping the back relatively straight, a typical deadlifting posture.

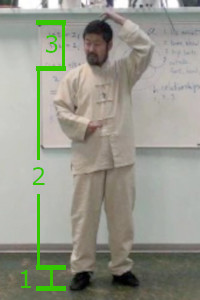

He introduced the Three Cylinder Model to explain the mechanics of this lift, describing the body’s mechanics as a projection on the sagittal plane. In this case, the body is seen as a series of vertical cylinders stacked on top of each other: “Now there is a vertical [series of cylinder stack on top of each other, labeled] One, Two, Three.” This Three Cylinder Model operates using the same relationship logic as the Three Rings Theory:

|

|

This Three Cylinder Model can describe vertical motions. This principle can be further generalized to movements that are more complex for example when the actions are carried out at different angles.

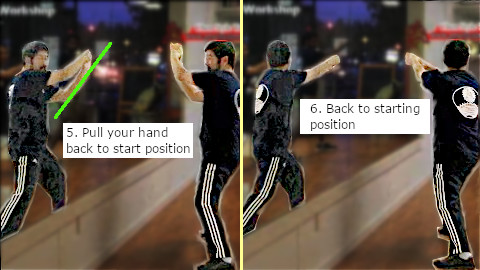

Demonstrating Favorable vs. Forbidden Relationships

Based on this model description, Master Chen demonstrated the correct actions. “So here Two [abdominal] can work with one [feet] here. [As a result, ] can you see [your body] drops [down to the ground].” Master Chen exhaled and allowed his head to sink down. He explained how this relationship allows for efficient sinking: “This [Three] can sink into here [Two].” Alternatively, he showed the upward movement: “or you can go like this,” inhaling and pushing his head up, demonstrating the favorable relationship of Two working with Three.

|

He then contrasted this with the Forbidden Relationships. Master Chen bent down and described the incorrect action: “You are not allowed to do this [bend the head to meet the foot. This is Three going to One].” He lifted one of his legs to demonstrate another forbidden action: “Whenever you do this [lift your foot up.] It is One trying to reach Three, causing you to fall.” |

| Returning to the correct lifting posture, Master Chen explained the ideal sequence: “When you lift something here, you want to do this [bend the knees first. This follows the theory of using the favorable relationship of Two going towards Three].” He concluded by contrasting this with an incorrect action: “If you want to lift it like this [by bending over so that you are exhibiting the Forbidden relationship of Three moving towards One]. Your body mechanics are wrong [and you could fall forward.]” |

|

Master Chen concluded his thoughts on the general applicability of Tai Chi mechanics: “So that’s one example to show that why I believe the Tai Chi mechanics will also work in your daily life. And so now once we recognize the human deficiency we need to work on it [and overcome this deficiency]. You have a system to combat it [and correct this bad habit]. And that system, in our [Practical Method] Tai Chi system, starts with [understanding the training of the] Positive Circle.”

Positive Circle – a training tool

Master Chen began by describing the training of the self-directed Positive Circle—a method that uses the free hand (the left hand) to guide the motion of the active hand (the right hand).

|

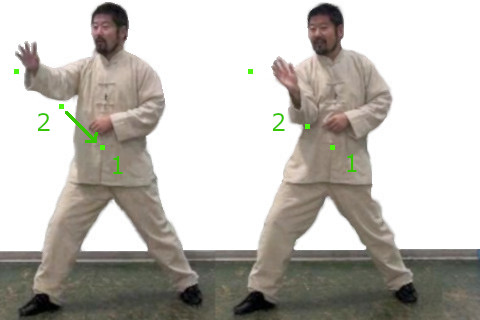

[Master Chen stands in a ready stance with his right hand out at shoulder level. The right hand is the active hand used to draw the Positive Circle, and the left hand is the free hand used to guide the right hand’s action.]

He started the instruction by stating, “So you do the three things here.” He was referring to the three discrete actions that make up the Positive Circle training:

|

|

|

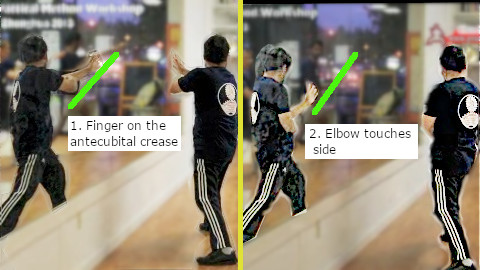

Step 1: In with Elbow

“You start here [in ready position]. One [‘In with Elbow’], you physically force yourself to use this hand [your left free hand] like here, pull this [right elbow] in [to your body].” [This action reinforces the idea that Ring 2 (R2) is working with Ring 1 (R1) and corrects the incorrect habit of Ring 3 (R3) moving towards R1.] |

|

Step 2: Turn with Waist

[This action trains the relationship of R1 working with R2. One key idea is that R3 is not involved in this action; as a result, the right hand should continue to point towards the starting position.] |

|

Step 3: Out with Hand

“Three [‘Out with Hand’], you [take your left hand and] stretch this [right hand] out [so that it is back to the original position].” [This action trains the correct relationship of R3 leading R2.] |

Breaking Incorrect Habits

Master Chen then explained the importance of using your free hand to guide these actions in order to break incorrect habits. He suggested that letting “Somebody else will do it [moving the active hand] for you. It’s even better because you get a more clear movement pattern [for training the Positive Circle],” explaining that this external guide to counter normal instincts provides superior feedback.

|

He demonstrated a common error when performing the Positive Circle without restrictions, noting, “If we do it [the actions] ourselves, can you see? Now the One [R1] is getting too close to the Three [R3].” [Master Chen carried out the first two actions of the Positive Circle but incorrectly, with the right hand being brought back past the elbow, illustrating the incorrect habit we “always like to do this.”] |

| Master Chen provided another example of an incorrect action, where the head is allowed to lean forward at the start of the Positive Circle. He explained, “If you do a little bit of this [letting your head to lean forward], see this is [application of the Three Cylinders Theory with the head] getting too close [to the feet].” |

|

Matter of Perspective

Master Chen concluded by summarizing the conceptual framework. Pointing to drawings of three concentric circles, he stated, “So this is the theory of the Three Rings of Tai Chi.”

He then clarified the specific perspective of this theory, noting that when instructors “talk about [the components] One, Two, Three, we’re talking normally about a lateral system.” [Master Chen described a system where each component is on a line, like the three components of a lever: the location of the applied force, the pivot, and the reaction force.]

Master Chen reminded his student that the Three Rings Theory is not about this linear model but about a different perspective, explaining: “When we talk about the Three Rings, we’re talking about looking at you from the top down. You see the three functional rings of the body.”

He concluded by asking, “Do you have any questions?”

Resolving Naming Convention Discrepancies

Initial Question

Master Chen began by addressing a great question from a student who had noticed an apparent contradiction in the models.

The student stated his understanding: “I think you said this [in describing the Three Ring Theory]. You’re saying that the One, the Two, the Three. The One is the fixed part.” The student correctly mapped this to the anatomical example: “Normally you can think of that as the core [Ring 1 (R1)] versus the elbow [Ring 2 (R2)] versus the hand [Ring 3 (R3)]… In your other example, though, you’re saying as you’re lifting something, the part that doesn’t move in that case is the foot [which you defined as One]. [Above the foot is Two and the head is Three].”

The student highlighted the issue: in the Three Ring Theory, R1 (One) runs from the head to the tailbone; yet in the Three Column Theory (vertical segments), Column 1 (One) is defined by the feet. The student followed up, seeking clarification: “So it’s not necessarily that the center is One [or that it is] fixed?”

Master Chen validated the confusion: “It’s actually, that’s a good question because everybody has that question.” He pointed out that what the student already explained was correct, but he needed to reiterate a key concept: the labels One, Two, and Three are merely conveniences, not absolute names.

The Importance of Consistent Sequential Labeling

Master Chen emphasized that the labeling system is flexible, but a convention is necessary to avoid confusion: “What it means is that it’s not necessarily true that you have to name the convention has to be this way. But very often it happens this [particular labeling system] is very convenient to use.”

He explained that labels can be reversed: “We can say that instead of torso is One, elbow is Two, finger is Three, [alternatively] you can say that finger is One, elbow is Two, and the torso is Three.”

However, he advised against changing the convention arbitrarily: “Why [do you want to have a different naming convention]? Why making a case of wanting to be different? Because if you are different, you understand the theory, you do it differently… We just unnecessarily create a layer of confusion that’s not really constructive to anything [in terms of deeper understanding of the Theory]. So just for the convenience, we [use this labeling system and] name this [Inner Circle as] One, this [Middle Circle as] Two and this [Outer Circle as] Three.”

Master Chen then introduced the two unwritten rules: The sequence must be preserved and each label must have meaning.

“But in naming so, the most important issue here is not whether this [Inner Circle] is [labelled] One or this [Outer Circle] is [labelled] One. It [the most important rule is] that this [Middle Circle] cannot be One. Do you understand that?” He clarified that the naming must be sequential: “You can’t randomly say this [Middle Ring] is One, this is [Ring] Two,. It [the naming convention] has to be sequential. [You can have a system that states from the inside going out:] One [Inner Circle], Two [Middle Circle], Three [Outer Circle], or [you can have a system that starts from the outside coming in] One [Outer Circle], Two [Middle Circle], Three [Inner Circle].”

The same rule applies to the vertical segments (the Three Cylinders): “So on the vertical here, it’s the same thing. Your foot is One, then this [waist] is Two, this [head] is Three… I can say I want to make this [head] One, this [waist] Two, this is [foot] Three. Sure [this alternative labeling is also valid but only] if your entire system is based on that [naming convention].” The utility of any convention depends on its consistency: “You can’t change halfway in explaining the same thing… As long as your system is like… as long as it’s from one end to another [following a logical sequence], you’re okay. But you can’t jump. You can’t say this is One, this is Two, this is Three. And you cannot just do it randomly. So it has to be sequential.”

The Special Property of the Two (The Joint)

|

Master Chen then explained why this sequence is crucial, especially the position labeled Two:

“The [label] Two indicates it’s here [in the middle].” This middle position is special because it moves and is shared by both ends. “This is a little bit difficult [to explain] because [in the model we have replace the physical position with a number] we [have] removed reality and used numbers in its place.” |

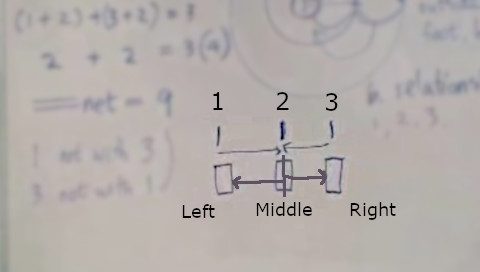

He illustrated with three vertical pegs (Right, Middle, Left). He noted that although we count them as “one, two, three,” in reality, pointing to the diagram, “There are just three [individual] pegs. And this is one peg [the left peg], this is one peg [the middle peg], this is one peg [the right peg].” The number Two represents the physical location of the middle peg.

“It [the Middle] happens to be half of this one [Right] is shared by this [right] side, half of this one [Left] is shared by this [left] side. That’s why that [the position labeled as] Two is very special. And that’s why that Two has to be in the middle.” Master Chen draws horizontal lines to connect the pegs to illustrate these shared relationships.

| In a real model, this middle position moves. “Why does it move? Because this [middle position] has a special property… that property here is that this one [middle position] can be used by this one [Right]. It can also be used by this one [Left]. That’s why this one in the middle is a joint.” Schematically, he drew a block beneath the middle peg and divided it: |

|

The end positions (One and Three) cannot be the middle position: “This one [representing the end] cannot be here [in the middle] because the One [end] here [ or Three the opposite end] does not have this [shared] property [which only the Middle possesses].”

Application to the Body

Returning to the body, Master Chen concluded: “So our body, every joint can be viewed [labelled and described as having the properties of] as Two. But the outside [the body extremities] is not.” In the context of the body, these components cannot be treated merely as identical pegs or blocks. Instead, each body part serves a distinct and particular function, making its corresponding label inherently meaningful. In the Three Ring theory

|

|

|

Applying the same convention to the Three Column Model but this time on different segments of the body. He provided different example of Two on the human body. Pointing to the knee, he states: “This [knee] is Two. Because this here [the tibia], half of it is shared by the foot, half of it [the thigh bone] is shared by the kua [hip/groin area]. ” Based on our convention, the tibia is designated One because, at this specific point, it is fixed to the ground. Conversely, the thigh bone is labeled Three because it is a moveable asset that can articulate with the kua (hip). |

Master Chen touched his hip, explaining: “The kua can also be Two because half of it is shared by the knee, half of it is shared by the torso.”

With this second example, Master Chen demonstrates the relative nature of the One-Two-Three convention. When the kua is designated as the primary Shared Connector (Two), it establishes a new operating model for analysis, causing a re-labeling of the surrounding segments. In this new model, the kua is the fixed Two, and other body parts, such as the previously independent knee segment, are now re-grouped as part of a larger unit.

To clarify the labels within this kua-centric model: Based on our convention for this particular analysis, everything below the kua, including the thigh bone, knee, and tibia, is collectively designated One (representing the connection to the new proximal or inner segment). Conversely, everything above the kua, including the torso and the head, is collectively designated Three (representing the connection to the new distal or outer segment). In this context, the entire leg and the entire torso function merely as the two components that the central Two (kua) connects.

Master Chen noted the satisfying coincidence: “Anything that we use the number Two is because there are two of it.” The label references the middle location and the fact that it is composed of two equal, shared parts.

He finalized the numerical definitions:

“So this is the theory there.” |

|

Master Chen clarified that his Three Ring and Three Column models use the labels One, Two, and Three as sequential conventions, not absolute names; therefore, the numbering sequence can be reversed (e.g., from inner-to-outer or outer-to-inner) for convenience, provided the system remains consistent. However, a convention is chosen where One represents the Fixed Asset (source, origin, or Inner Ring) and Three represents the Moveable Asset (extremity or Outer Ring). Crucially, the label Two must always represent the middle position, as it is structurally unique: it acts as a joint or shared segment, containing two halves used by the sections designated as One and Three. Consequently, when applied to the body, Two represents any joint (like the knee or kua), while the single, non-shared, end segments (such as the torso, foot, or hand) are always labeled One or Three depending on its function.