|

Gaze upon the night sky—a vast array of distant lights, each one a mystery, seemingly without end. So too is the boundless knowledge offered by Master Chen’s videos. To decipher the secrets of the cosmos, one must first learn to watch the stars; similarly, to unlock the profound art of Taijiquan, you must turn your gaze to this luminous, virtual library. Master Hong’s practical ‘Doa system (多)’ gave us the essential keys, the steps to repeat until they become instinct. |

| Master Chen, using the grace of modern technology, complements this by casting the full brilliance of his art across the digital sky. But the brightest galaxy remains invisible to the careless eye. Just as the spectacle of the heavens requires you to lift your head and truly see, the wisdom held within those videos will only be revealed when you approach them with focused, sustained intention. | |

| (This article is based on videos from the Practical Method YouTube channel.) |

|

This very approach—of total transparency and commitment to principle—is what Master Chen has embodied from the start. Every lecture and demonstration has been intentionally recorded, forming an unbroken, luminous video trail of his complete understanding of Taijiquan’s principles and applications. He approaches each session without a script, effortlessly conveying complex, novel ideas with clarity and simplicity. This method is the direct response to the weighty responsibility defined by his teacher, Master Hong, who instructed:

|

“Being the teacher, Is a heavy responsibility. First of all, You must be truthful. Understand the theories, Avoid superstitions. Demonstrate in detail, And don’t gross over.” (為人師,責任重, |

|

Master Chen’s teaching is a direct fulfillment of this mandate. By hiding nothing, he argues that the art possesses no secrets—only basic principles that, as he often observes, must be found in all things. To this end, his profound dive into the Eight Methods of Taijiquan extends traditional models, using the analytical precision of the concave circle, gears, and three-dimensional mechanics to demonstrate foundational truths in compelling detail.

|

|

Introduction

Part 1. Four Primary Energies (正劲)

Part 2. Four Diagonal Energies (隅劲)

Part 3. Mechanical Models

1. Lever (杠杆)

2. Wheel (轮) and Spinning Disc (转盘)

3. Concave Circle (凹圓) and Gears (齿轮)

Based on the video Taijiquan Peng Lu Ji An UTS Open House 4/7 Mar 31, 2018.

|

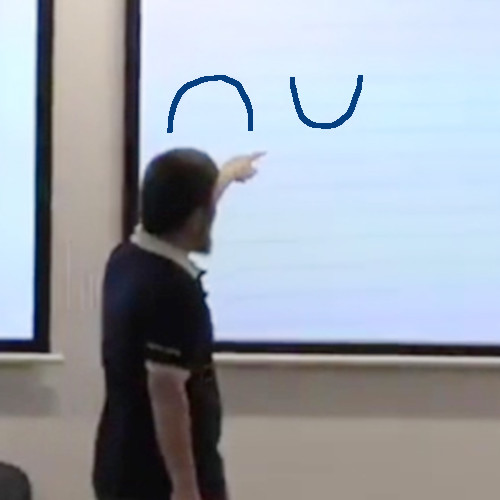

Master Chen starts the lecture by drawing a diagram showing both concave (凹 Āo) and convex (凸 Tū) curves and these curves is displayed on the screen.

In general, a concave curve bends inward (like the entrance of a cave), while a convex curve bends outward (like the surface of a dome). Mathematically, a function is convex if the line segment between any two points on its graph lies entirely on or above the curve; conversely, it is concave if the segment lies on or below the curve. |

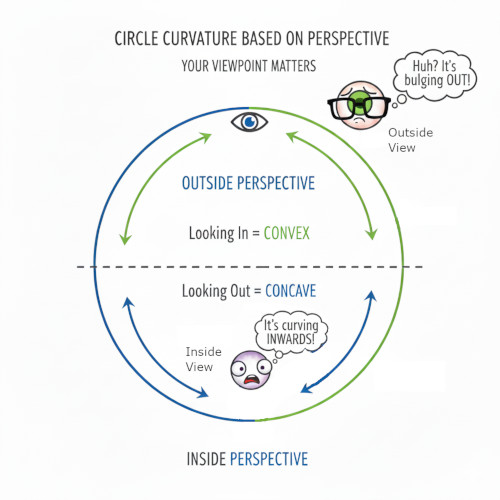

However, when analyzing a self-contained shape like a circle, these definitions depend on which side of the curve you are observing. As illustrated in Figure 10, a circle presents both concave and convex curves from different viewpoints:

In essence, the interior of a circle is a concave region, while its exterior is a convex region. Thus, labeling a circle as simply “concave” or “convex” requires specifying the frame of reference. |

|

Refinement of Taiji Practice: Concave vs. Convex Posture

|

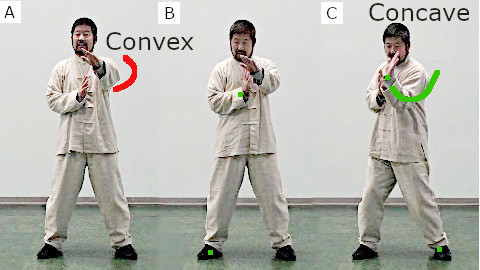

Master Chen begins his demonstration of The Practical Method by performing the first movement of the Yilu form, Pound the Mortar. He executes this initial action with his elbow sharply raised, causing his entire arm to form a convex shape. This posture is illustrated in Figure 11A with a red curve highlighting this convex shape. This initial posture is then critiqued by Master Chen, who notes that the philosophy of The Practical Method “does not allow this action.” Indicating that the convex shape is considered undesirable. |

Master Chen then immediately transitions to performing the proper posture, as prescribed by The Practical Method and shown in Figure 11C. Describing the correct execution, he emphasizes the change in structure: “So you start here, with the finger lock in space. The elbow has to be dropped into the center line.” By dropping the elbow, the arm’s shape completely changes. “So here, the arm is now in the shape of a concave curve,” he states, further clarifying the geometry: “I use the word ‘halfpipe‘ to describe this concave shape.”

The Power of the Concave Shape

|

The significance of this concave structure lies in its ability to reflect and redirect incoming forces back to their source. Master Chen uses a physical analogy to explain this powerful property: “You look at a skateboarder going really fast hitting that half pipe, the stronger you hit the half pipe, the more you come back.”

He then illustrates this principle with a practical application. Instead of engaging in direct confrontation, such as “fighting like this” (implying a rigid, head-on block), the practitioner should “pretend to do this” (demonstrating a soft initial block with the forearm with elbow pointing away from the body). |

|

When the opponent begins to apply power to overcome the apparent block, the practitioner must instantly change the structure: “You go with your elbow into this here.” Master Chen shows how dropping the elbow so that the elbow is pointing away from the opponent. This converts the forearm into a powerful concave curve. He concludes: “So the opponent’s force goes like that, redirected back to the opponent.”

Doctrinal Differences

Master Chen clarifies that while all Taiji styles utilize methods of redirection, the consistent emphasis on the concave shape is unique to Master Hong’s lineage. “This is just a particular technique that the Practical Method uses.”

| He contrasts his style with others, such as the Yang style, which he notes primarily utilizes the convex part of the circle. An example is the technique of Ward Off in the Yang style is shown in Figure 12. In contrast, practitioners of The Practical Method are trained to only very temporarily stay in the convex part of the circle. They are taught to “immediately go into this one here,” the concave shape, and “hold this posture for a long time.” This commitment to the concave structure is the hallmark of the method’s unique approach to neutralizing and returning force. |

|

The Circular Foundation of Taiji Power

Master Chen begins by establishing the fundamental concept: all Taiji techniques are based on the circle. While every style references this circle, the distinction between them is dependent on which specific parts of the circle they emphasize and utilize.

In the Chen Style Practical Method, Master Chen’s teacher stressed three key types of power derived from this circular model, though many variations exist. To illustrate the concept, Master Chen uses the analogy of a bicycle tire with spokes. He explains that the eight fundamental techniques of Taijiquan (péng, lǚ, jǐ, àn, cǎi, liè, zhǒu, kào) are all based on the actions and structure of this tire.

Mapping Power on the Circle

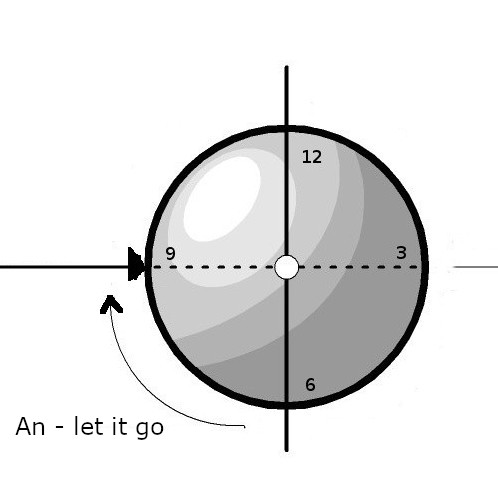

Master Chen describes the movement of energy along the established perimeter in a clockwise direction. The core principles and analysis remain identical even if the energy is moving counter-clockwise. For the purpose of this mechanical model, the influence of gravity is not considered in the energy analysis.

Master Chen describes the movement of energy around this perimeter:

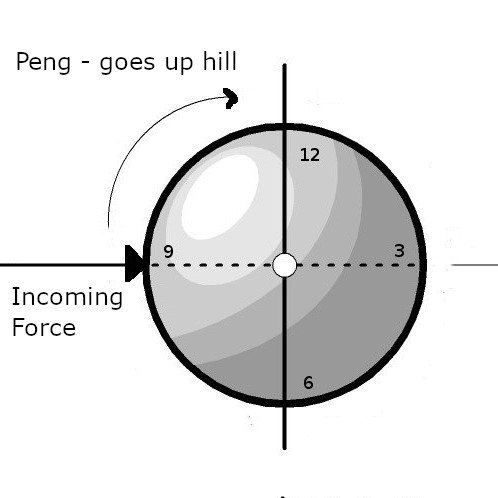

1. Péng (Ward Off) – The Uphill Climb (9 o’clock to 12 o’clock)

|

Imagine an opponent’s force coming directly toward the center, hitting the equator of the circle at 9 o’clock. The Taiji practitioner uses intention to direct this incoming force upward along the perimeter toward 12 o’clock.

This upper arc, from 9 o’clock to 12 o’clock, is Péng (Ward Off) energy. Master Chen likens this to pushing a wheelbarrow or riding a bicycle uphill: the power required increases steadily, making the effort feel very strong. The practitioner works hard, hoping when they reach the peak at 12 o’clock, they can coast downward. |

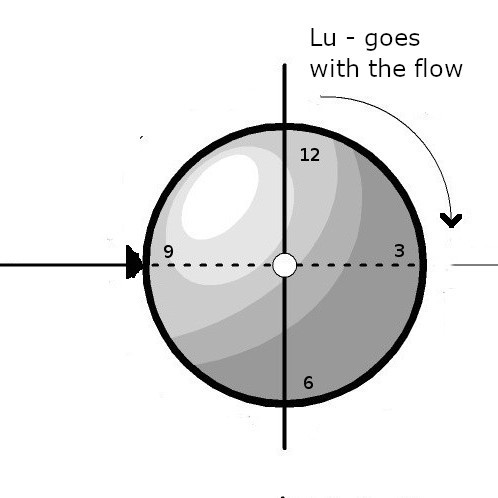

2. Lǚ (Roll Back) – The Efficient Coast (12 o’clock to 3 o’clock)

|

The technique immediately following Péng is Lǚ (Roll Back). This means the practitioner now follows the opponent’s force and moves with it, which is highly efficient. As the energy travels from the peak at 12 o’clock to the midpoint at 3 o’clock, it’s still following a downward curvature. Master Chen notes that if the opponent’s force has the yielding quality of water, Lǚ allows that water to simply flow downward with minimal resistance. |

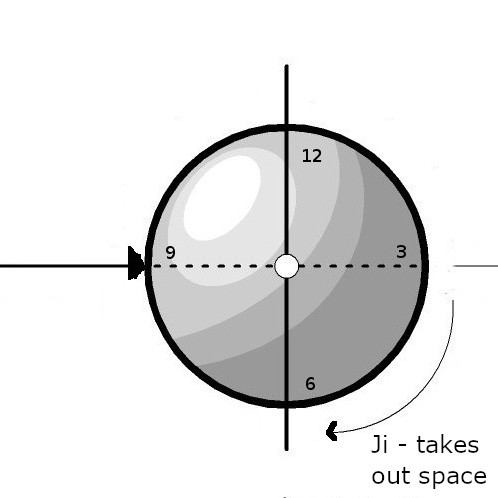

3. Jǐ (Press) – Reaching Empty Space (3 o’clock to 6 o’clock)

|

After the 3 o’clock position, the opponent’s power is no longer just water but has gained momentum and structure. As the energy continues to move from 3 o’clock to 6 o’clock, the practitioner maintains control by using that momentum and friction to accelerate the opponent’s fall.

This section is called Jǐ (Press). Crucially, this part of the technique involves “taking out space“: the contact becomes so light the practitioner may not even be touching the opponent anymore. By the time the opponent’s energy reaches the 6 o’clock position, they have been guided into empty space. |

Master Chen describes the effect: “It is like your opponent is on the cliff.” The entire process of enticing him onto the cliff is Jǐ energy.

4. Àn (Push) – Pushing Off the Cliff (The Finish)

|

The final, decisive action of pushing him off the cliff is the ‘Àn‘ (Push) energy. This represents the conclusive discharge of force after the opponent has been fully neutralized and placed into a precarious position via the previous three energies. |

Practical Application: Redirecting Force with the Circle

|

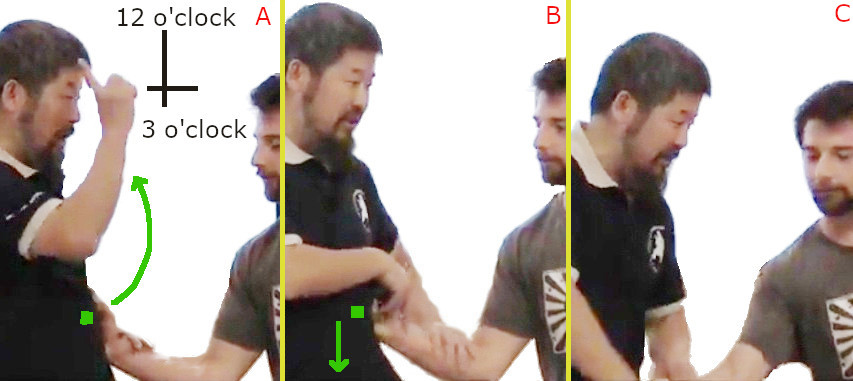

Master Chen proceeds to demonstrate the previously explained principles of circular energy with a student. He begins, stating, “I’ll show you the directions [that energy can be directed] on the body,” and sets up a defensive scenario.

A student initiates an action by approaching Master Chen’s left side and placing a closed right fist directly onto Master Chen’s Dantian (the lower abdomen energy center). |

|

This represents the starting point for a push, as illustrated in Figure 13A. The diagram includes a reference grid marked with 12 o’clock and 3 o’clock positions, and a green arrow indicating the direction of energy movement. Since the energy is coming from left (3 o’clock), the energy movement is counter-clockwise.

Master Chen mentally maps a circular clock face onto his body relative to the incoming force, establishing a coordinate system for the impending push:

- The student’s point of contact on the Dantian is designated as 3 o’clock.

- The top of his head is designated as 12 o’clock.

The student then applies pressure. Master Chen ensures there is just enough initial resistance to let the partner feel contact, explaining: “I make him feel it’s like this here,” meaning the fist cannot simply push straight through his body. He acknowledges the danger of confronting the attack directly: “We are both strong at this point, but I’m not confrontational.”

He notes his anatomical disadvantage: the student’s punch is “very straight” and backed by the solid “bones” of the arm. In contrast, Master Chen’s Dantian is protected by “no bones”—just “blood and guts” inside. Directly opposing this force would only “hurt.”

Master Chen then describes the Practical Method’s solution: redirecting the force by instantly shifting his internal structure. He starts by applying Péng (Ward Off) energy, which he initiates by subtly readjusting the position of his Dantian—a shift visible as an upward tilt of the pelvis.

This slight, upward movement directs the opponent’s incoming energy to follow a anti-clockwise curved path traveling from 3 o’clock toward 12 o’clock. This action is the physical embodiment of the uphill climb of Péng. The energy transfer is illustrated as a green arrow in Figure 13A.

Once the energy is led to the top point, at the 12 o’clock position (the top of his head), the opponent’s power is neutralized. Master Chen explains that at this moment, “I made his energy almost dissipate.” The student’s fist is still on the Dantian but the energy of the punch is no longer there.

He concludes the sequence by applying Àn (Push) energy directly to the student’s right hand, which had been anchored on the Dantian. This final technique immediately capitalizes on the opponent’s misdirected forward momentum, causing him to lose balance and stumble forward. As shown by the straight green arrow in Figure 13B, the downward application of energy causes a separation (Figure 13C). The technique seamlessly transitions from the defensive Péng to the offensive Àn, successfully demonstrating how a mechanical model of a wheel can manage and redirect a straight-line attack.

Practical Application: Jǐ (Press) and Entering Empty Space

|

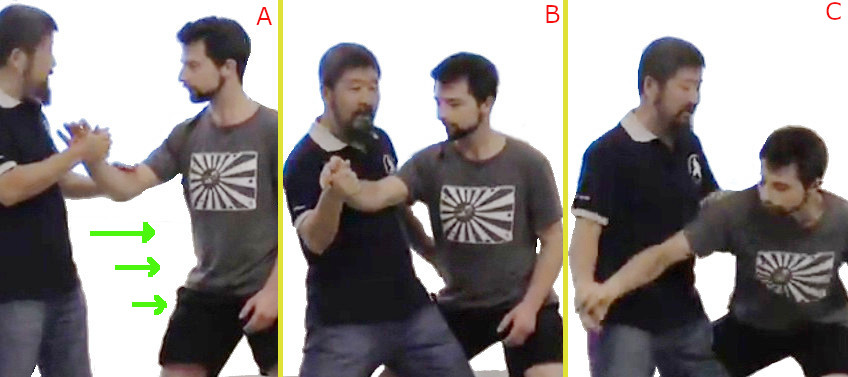

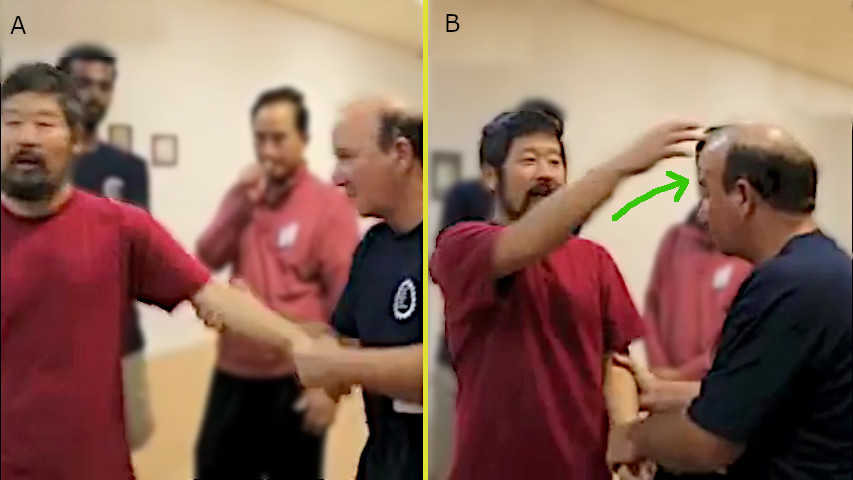

Master Chen sets up another demonstration, allowing his student to push his chest directly with a forearm. This initial confrontation is shown in Figure 14A.

Master Chen describes the instinctive reaction: “Now you push me, you see at this point we’re fighting.” He highlights that a direct exchange immediately establishes a struggle for power. |

Master Chen points out the critical moment of transition: When the opponent’s forearm contacts his chest, he subtly performs an action—a yield or a shift—that causes the opponent’s arm to momentarily pause. “At this point here, when I do this here, some space is created” between the opponent’s raised forearm and Master Chen’s body. The green arrow in Figure 14A highlights this empty space and the movement to take up this space.

As soon as that vital empty space is created, Master Chen capitalizes instantly: “I go in like this.” He demonstrates this by stepping into the void left by the opponent’s momentary pause or extension, as illustrated in Figure 14B.

He identifies this maneuver as the core of Jǐ (Press) energy. The moment space is created, “there’s no more need for fight.” The goal isn’t to push, but to “fill it in.” This means that instead of meeting the opponent’s touch with resistance, the practitioner can directly “go in” and occupy the advantageous position. Once the empty space is claimed, Master Chen can then execute the final offensive technique of Àn (Push), leading to the successful dislodging of the opponent, as shown in Figure 18C.

The Principle of Manipulation

Master Chen contrasts this technique with typical reactions that lead to a direct confrontation characterized by fruitless pushing and shoving. He concludes by defining the essence of Taiji techniques: they are about “how you use body rotation to manipulate your opponent into different structures.” The victory lies in maneuvering the opponent into a precarious structural position, thus rendering their physical force ineffective.

The Taiji Strategy: Enticement and Displacement

Master Chen summarizes the core principle of Taiji techniques: “The Taiji method is that I use one touch and move my own body.” The goal is not brute force, but calculated deception and structural breakdown.

He offers a powerful metaphor to illustrate this strategic intent: “You have to remember you are trying to entice him onto a place and push him off.” While this “cliff” or “place” is often conceptual, the physical result is displacement.

The Carpet Analogy

|

A more relatable, everyday analogy further clarifies the strategy of enticement and displacement: Master Chen presents this situation. “Or, there isn’t such a place [as a cliff], but there is a piece of carpet [that your opponent is standing close to], and he’s already holding the other end of the carpet. [The goal is to lure him onto it.] I say, ‘Sure, here, come, come,’ and I go like this [making a move to trick him onto the carpet]. When he’s on the carpet, I yank the carpet, so you pull the rug underneath him.” |

|

Drawing from these metaphors and analogies, Master Chen confirms that enticement and sudden structural collapse are the core objectives underlying the eight techniques of Taiji.

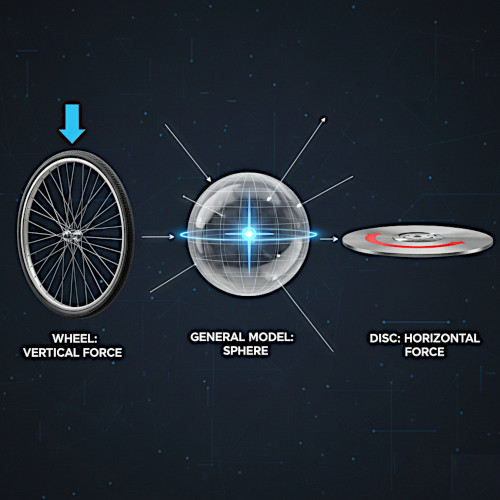

Expanding the Model: From Wheel to Sphere

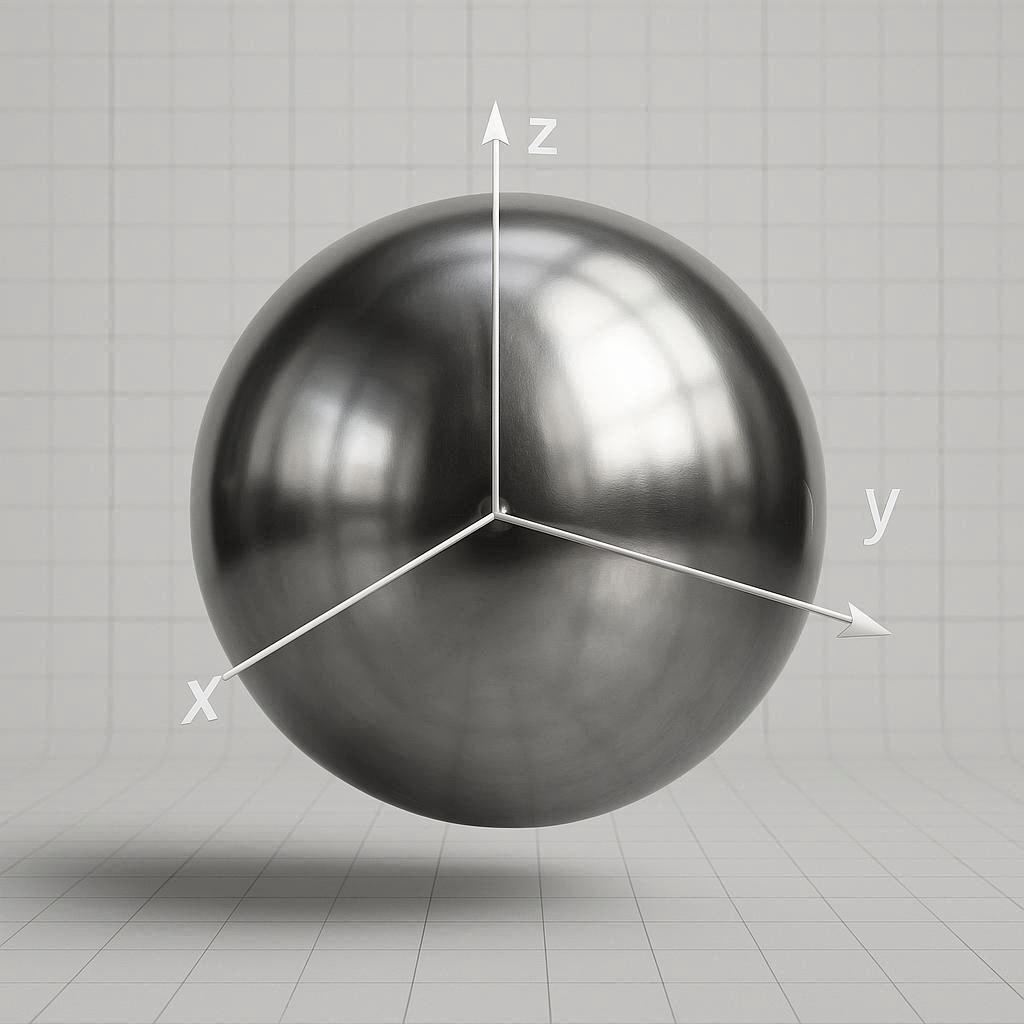

Master Chen reiterates that the diagram of the circle, divided into four sections, represents the four main directional techniques: péng (Ward Off), lǚ (Roll Back), jǐ (Press), and àn (Push).

|

However, Master Chen explains that the remaining four “corner” techniques—cǎi (Pluck), liè (Split), zhǒu (Elbow), and kào (Shoulder/Bump)—are also integral to the system. Fully explaining these techniques requires the practitioner to extend the two-dimensional mechanical model of the wheel to the three-dimensional model of a sphere. This conceptual shift to a spherical model is essential, as it allows the practitioner to visualize and execute power not just along a flat plane, but simultaneously in all directions. This extension is necessary to account for and explain actions like a vertical wheel, a horizontal spinning disc, and forces acting across any dimension. |

Separation and Counter-Rotation: The Gear Mechanism

Master Chen continues, explaining that once the foundation of the eight primary Taijiquan techniques is understood, the next step is the crucial concept of body separation and counter-rotation.

The sequence begins with establishing the initial position, or ready stance, characterized by the hands slightly raised. This specific posture is the foundation for the first move of the Yilu: Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar (Jīn gāng dǎo duì 金刚捣碓).

|

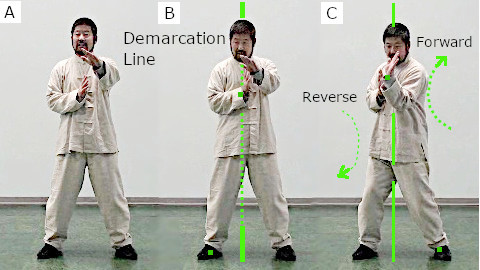

Master Chen demonstrates the application, stating, “So here, at the beginning, we’re fighting like this,” engaging the hands and arms in close contact with an imaginary opponent. The left arm rises to guard against the opponent, and the right hand protects the body. This starting posture is visually detailed in Figure 15A.

To achieve maximum power and effective neutralization, the body must be conceptually divided. Master Chen clarifies this by visually creating a demarcation line: |

|

“Now we put a demarcation here [on the main center line.]” This vertical line splits the trunk through the center, enabling the left and right halves of the body to operate as two independently functional units. Figure 15B’s green dashed line illustrates this critical central demarcation.

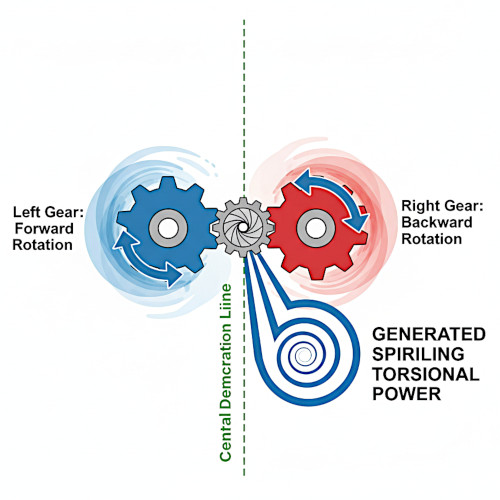

Master Chen explains the action of these two separated body sections, likening their movement to opposing gears turning against each other:

- The right rear half of the body executes “half of it,” rotating backwards around the central axis.

- The left front half of the body performs “the other half,” simultaneously rotating forwards.

The essential principle of this technique is counter-rotation: the two separated body sections move simultaneously in opposing directions. This is not a simple turn, but a powerful, torsional action where the front and back of the trunk twist against each other around the central axis. Master Chen demonstrates this dynamic with the phrase, “The two will go like this,” illustrating how this counter-rotational twist generates a spiraling torsional force that integrates the body’s energy into a single, cohesive action. This force is the precise mechanism used to manipulate and unbalance an opponent, as visually represented in Figure 15C.

Developing Mechanical Taiji: From Sensitivity to the Gearbox

Master Chen explains the key shift in training emphasis within the Practical Method: moving beyond beginner-level responsiveness to developing an integrated gearbox within the body.

He notes that at the very beginning of Taiji study, the practitioner’s focus is on following the opponent’s action. This results in a classified, reactive form of combat: the opponent attacks, the practitioner responds with Péng (Ward Off); the opponent counters with Lǚ (Roll Back); the practitioner reacts with Jǐ (Press). This simple chain of reaction defines initial Taiji combat.

The Gearbox: A Mechanical Body

|

In contrast, the Practical Method seeks to transition the body into a machine. Master Chen demonstrates the immediate response required by the system: countering an attack is not a simple block, but a simultaneous, complex action that requires the body’s structure to instantly form a concave shape in the front side paired with a backward turn of the rear—the essence of counter-rotation.

“This is the starting of a gearbox,” Master Chen states. The training goal is to develop the body to have “18 gears rotating at different directions.” Once this internal gearbox is fully operational, the practitioner’s actions become mechanical and automatic. |

|

Differentiating Mechanical vs. Sensitivity-Based Taiji

Master Chen contrasts this mechanical approach with the majority of other Taiji styles, which are still sensitivity-based. He credits his teacher, Master Hong, with creating this concept of Mechanical Taiji.

Conventional sensitivity-based Taiji is described as follows: “You touch your opponent very lightly. You go and sense what he’s going to do and then you gather your information and strike him at the right time, very fast or sometimes block him so he can’t move and use that type of techniques.”

From the perspective of the Practical Method, this sensitivity-based combat is only at a beginning level. The goal is that “later on the techniques of Practical Method become non involving.”

Non-Involving, True Self-Defense

The advanced practitioner in the Practical Method moves toward a state where “I don’t involve the opponent anymore. My whole body becomes a machine by itself.” The mechanical rotation of the internal gearbox is so powerful and continuous that it creates an external danger that no one would dare confront directly: “When the big gearbox is rotating, who wants to put the hand in it? Right? This type of combat is truly self-defense.” The opponent is defeated not by a discrete technique or block, but by the overwhelming, spiraling power of the practitioner’s rotating structure. Master Chen concludes: “Nothing from the gearbox will come out and strike you.” meaning the opponent is defeated by their own structural failure against the irresistible, mechanical turning of the Taiji body.

The Defensive Core: The Story of Master Hong’s Students

|

Master Chen emphasizes that the Practical Method is fundamentally a self-defense martial art, illustrated by an anecdote concerning the students of his own teacher, Master Hong Junsheng.

Master Hong began teaching in 1945, and by 1982, his method had become widely known as a purely defensive art. |

Master Chen recounts a story from that era: “My senior Taiji brothers, four of them, went to Shanghai [and] got into a fight on the bus. The people who they fought with them went to jail. My Taiji brothers came home without consequence.”

The reason for their immediate dismissal by the authorities was striking: as soon as the students identified themselves as students of Master Hong Junsheng, the police officer said, “Go home.” The police reasoned: “We know your method has no strikes. You can’t fight people.”

Master Chen explains the true cause of injury to the opponents: “They got hurt because they got into the gearbox.” He clarifies the nature of the Practical Method practitioner: “We don’t know how to fight people. It’s only when they come in, we can twist them and do whatever.” If the opponent doesn’t initiate an attack, the practitioner has no response, as the system “don’t have attacking moves.”

|

He draws a comparison to emphasize the purely defensive nature of their movements: “The same as saying you do yoga stretching. Then somebody says, ‘Oh, that guy hurt me with his yoga.’ Everybody will say, ‘No, no, no,’ because how can yoga hurt someone?”

In the same way, others would suggest the accuser “probably fell down by yourself” because while the moves of the Practical Method are powerful, “there are no offensive moves.” |

|

Master Chen concludes by reiterating the practitioner’s central mission: “So our job is to create a gearbox.” The body is a continuously rotating machine, and if anything comes “within reach of my body, we break it with the gears.” Crucially, “there are no moves that aggressively seek something not within reach.”

If the opponent’s force isn’t caught by the spiraling gearbox, it is instead immediately deflected with the concave circle—the primary structure for warding off incoming power. “These are characteristics of the Practical Method.”

Yilu Training: Refining the Body for Combat

Master Chen concludes his lecture by demonstrating the initial thirteen movements of the Yilu (First Routine).

He explains the standard training method: “Normally we do it [the form slowly and carefully] because the system is very long and the requirements are very strict. All of Yilu’s 81 moves must be done like that.” This raises a common question for modern students: “How can something so slow be a martial art?”

Master Chen observes that “We modern people are not patient,” despite Taiji being classified as a martial art. Most other martial arts styles offer a sense of achievement within two or three years, but Taijiquan is different.

He clarifies that the martial application—the actual fighting form—is the Canon Fist (Erlu, the second form). Practitioners “are not allowed to use Yilu practice for fighting.”

Master Chen recounts his own strict training under Master Hong Junsheng: “My master says eight years of this [slow, methodical training of Yilu] before I show you the second set.” Because he had to leave China to study in Canada after only five years, he had to plead with Master Hong to teach him the Erlu before the mandated eight years. Master Hong complied, but only to show him the postures so he could remember them, not to teach him their true combative functions.

Master Chen later understood the profound wisdom behind Master Hong’s insistence on slow, correct Yilu training with no power. He confesses that he had initially broken the rules by practicing the movements with power—an approach he now recognizes was incorrect.

Yilu’s sole purpose is to let you understand and train your body. Over time, this slow, deliberate training instills a fluid movement which is absolutely required for the fast, complex actions of the Canon Fist. “We say the body has to be open.”

Your untrained body represents initial raw material. You must refine this raw material by training until the body starts to have fluid motion so that you can reach any position with inherent stability and move through the appropriate range of movement. Critically, these actions are not dependent on external factors such as speed or brute strength.

Master Chen finishes with a pointed observation about the modern student’s impatience: “You know, the old things were based on old people,” who had the patience for slow work. “But today people are very well trained—lots of beef.”

4. Dimensionality

A Sphere in Three Dimensions

Based on the video Trailer – Peng 掤 Lu 捋 Ji 挤 An 按 – 陈式太极拳实用拳法 Jul 3, 2025.

|

Master Chen sits on the ground with his students surrounding him as he demonstrates the concepts of Eight Methods (Bā Fǎ) of Taijiquan. One of his students uses one finger on each hand to hold the side of a ball. This effectively fixes the y-axis, creating a rotational axis along the z-plane. Master Chen then uses his finger to point directly at the x-axis, explaining the concept of a precise strike:”[Imagine this sphere is a billiard ball.] |

| If I strike the sphere exactly on the x-axis, [it’s a head-on collision.] This is dead on. The only chance for a perfect strike is if my aim is precisely right. [There is an absolute line—the x-axis—that I must stay on.] I’m aiming at that dot that crosses at the center, the origin of the coordinate system. [It’s like aiming at the center of the cue ball.] If I find that center, the full force of my power is directed through the middle of the sphere. [The result is a direct, linear push, a perfect ‘peng’ (膨, ward-off).] |

|

|

“But the problem is, I often think I’ve found that direct center. But my strike is actually like this: [My aim is slightly off from the center on the x-axis.]

“So this point here [the top of the sphere], put your finger here. This is the very top.” Using a clock analogy: The force is coming straight towards the sphere along the x-axis, which is the 9 o’clock position in the z-axis. The top of the sphere is the 12 o’clock position. |

| Master Chen explains that any hit that is not aimed directly at the absolute center causes the ball to deflect or rotate towards the 12 o’clock position. “And as I strike the ball off-center, [the force is converted, causing the ball to rotate from the 9 o’clock line upward towards the 12 o’clock line.] This rotation is a climb. The energy path becomes higher and higher. Can you see? It used to be aimed here [at the 9 o’clock position], but the energy path now moves upward. |

|

This higher, climbing path uses up energy. You have to power up to achieve it. [In Taiji, this sensation of upward, expansive energy is a strong manifestation of] that’s called a Peng (Ward-Off). It feels strong.”

Master Chen continues the description of the off-center strike’s energy path: “Once that dot [the point of contact/energy] reaches here [the 12 o’clock position, the peak of the upward climb], the path changes. It’s downhill from there, moving toward the 3 o’clock position here, and back down to the middle level [the x-axis, but on the far side of the sphere].

This path [the descent from 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock] is easy. That’s Lǚ (Rollback). Lǚ feels like you’re simply going with the opponent’s momentum. It feels this way because halfway through the movement toward the 3 o’clock position, the descent is smooth. Momentum naturally gathers and it falls downhill. That part [the falling/yielding action] is totally empty and automatic.”

This segment masterfully transitions from the two dynamic techniques (Peng and Lǚ) to the two finishing techniques (Jǐ and Ǎn), using the circle analogy to map out the entire cycle of energy.

Master Chen describes an example with a student: “I was performing the first two techniques (Peng and Lǚ) on you, but at the end, you overstretched. You went past the point of Lǚ and into empty space. You fell down by yourself. What’s the name for that?”

Master Chen elaborates: “Let’s refer back to the sphere:

- The first one is Peng (Ward-Off) [from the 9 o’clock position to the 12 o’clock position].

- The second one is Lǚ (Rollback) [the downhill path from 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock].”

Pointing to the area immediately past the 3 o’clock position on the sphere: “At this point here [the transition area past 3 o’clock], this part is practically Ǎn (Press/Push Down).”

The term ‘practically‘ is used because in most situations, after reaching the 3 o’clock position (the end of the easy descent), unless you can consciously hold onto the surface, you will fall, which is the nature of Ǎn.

Master Chen explains the mechanical placement of Jǐ versus its application:

“In this purely mechanical model, the theoretical Jǐ (Press/Squeeze) part is not strictly placed here, but [from a theoretical perspective, Jǐ] is mechanically located between the 3 o’clock to the 6 o’clock position.”

Master Chen elaborates on the application of the Jǐ concept: “The application of Jǐ happens when you move [creating separation or an opening between us], and I move in to immediately occupy this empty space. That is Jǐ—squeezing into a gap. This ball has no empty spot. In contrast, your body and structure have empty spots. I walk in to fill it. That’s Jǐ.”

Master Chen returns to the sphere model, pointing to the section between the 6 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions. He clarifies the transition to Ǎn: “So, this section [from 6 o’clock back up to 9 o’clock] is Ǎn.”

He provides more detail on the practical transition between Jǐ and Ǎn: “If we consider that your opponent can still hold on [to the surface of the sphere, from 3 o’clock to 6 o’clock], that third part is Jǐ. [In practical application, Jǐ means] to press in and fill up all the empty space until you are totally at the bottom [of their structure, with nothing left to hold onto].

You can say you are on the edge of a cliff with a 90-degree drop. There’s nothing to hold on to. That situation is Ǎn.

As discussed previously, you can say the section [after 3 o’clock] is already Ǎn because, for most people, [after the quick downhill Lǚ] you can’t hold on anymore. As long as you are able to hold on to their structure and not fall, it is Jǐ.”

Master Chen demonstrates the practical application of this theoretical model with his student.

|

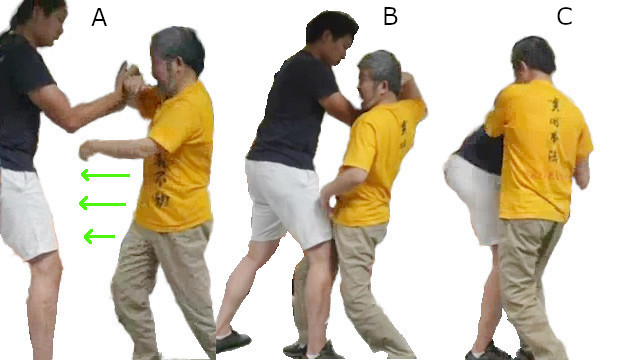

Master Chen starts by asking his student to reach out with his hand. “So when we stand up like this here,” he instructs. The student reaches out with his right hand.

Master Chen continues: “I pretend to do this.” Master Chen intercepts the student’s reaching right hand with his own right forearm, as seen in Figure 16A. This initial contact can be classified as the technique of Peng (ward-off). |

“Give me a little bit [of] interaction,” Master Chen requests, prompting his student to continue to press forward. By enticing his student’s forward movement, Master Chen is applying the technique of Lü (roll back). “Okay. See this interaction here created emptiness.” This initial contact and the resulting empty space (highlighted by green arrows) is shown in Figure 01A.

Master Chen proceeds: “and I went like this.” Master Chen steps forward into the empty space. “This is a Jǐ,” Master Chen explains. “Initially, there’s nothing there. Because of my technique of Jǐ here, which fills the space, now he thinks he has something—he has power and stability here in that position.” This position is shown in Figure 16B.

Master Chen concludes: “That feeling and power are illusionary. As soon as I withdraw…” Master Chen rotates his torso, and the final position is shown in Figure 16C. Master Chen explains: “Can you see he falls because he lands in a position that is empty. My Jǐ made him feel like, ‘Okay, there’s something here,’ but when that something is gone, you fall down.” That is a practical demonstration of Jǐ (press) and the resulting technique of Ān (push).

Master Chen described his experience training with his teacher: “Master Hong’s push was always a light touch; we felt fine, like we were still supported. We wondered: ‘Why is this considered high-level skill?’

|

Master Hong replied with a knowing smile, ‘I’ll show you.'”

He would touch you, then simply walk away, and you would fall. Why? Because he put you in a position where he was always supporting you. When he took that support away—when he goes away—you fall, because you were already on the brink. [You were already taken to the edge of the ’90-degree drop’ point of Ǎn.] |

|

When he goes away, you can’t follow him. There’s nothing left there to hold onto. Now you understand the skill?”

360 Degrees of Freedom

Based on the video Peng and Dimensions in Taijiquan Dec 24, 2014.

Master Chen let his student place one hand on his left shoulder and the other hand on his right forearm. The student began to push forward. Master Chen resisted and proceeded to describe the theory of Peng in this context:

|

“[His action, this push,] it’s totally [in one dimension.]”

Master Chen demonstrated this explanation by moving against the push on his right hand, immediately encountering the student’s resistance. “So here, this is his line [of force].” As seen In Figure 17A with a red arrow. |

The student then pressed again, and this time, Master Chen yielded, letting the pressure on his left shoulder push him backward. He described this action: “and this is also his line.” This action is shown in Figure 17B with a red arrow.

Master Chen then surprised his student by extending his left hand as his student pressed forward, stating, “but you see this is not your line.” This surprising move caused the student to stumble backward with very little effort from Master Chen. This result is shown in Figure 17C with a green arrow.

Master Chen explained, “So our body is in [3 Dimensions; actions can occur in all] 360° [directions—the quality of a circle]—meaning [there is a] 360 layers of structure. [Normal actions,] you can only use one [direction to attack me,] so I have total freedom to do whatever I want [in all the other directions to counter your attack].”

|

Master Chen let his student grab his arm with both hands. He described his reaction: “If I don’t tense up [when he grabs my arm,] I can do whatever I want [with any other part of my body], right?”

Master Chen contrasted this idea with the normal reaction of tensing up due to the grab: “But if I tense up, can you see [what my] whole body is doing? It means when you tense up, it means your body went into one dimension. All the other dimensions are not available to you anymore.” |

|

Master Chen concluded, “[For Practical Method training, the goal is that] you must be in all Dimensions. When you are in all the dimensions, you have Peng.”

Appendix

|

Master Hong Junsheng (洪均生) was a seminal figure in 20th-century Taijiquan, renowned for his pragmatic and analytical approach. He broke from esoteric or purely energetic descriptions of the art, instead providing a tangible, physically verifiable framework for how Taiji techniques function in martial application.

His direct student, Master Chen Zhonghua, continues this tradition, offering valuable insights that bridge the chasm between Eastern and Western thought. Master Chen acts as the definitive interpreter and technical amplifier of Master Hong’s legacy, tirelessly explaining the benefits and uniqueness of this analytical approach. His views are a direct and profound systematization of his teacher’s fundamental rule: “Throughout the entire form, there is nowhere that is not Peng Jin” (套路自始至终,掤劲无处不在). |

The “One Method” and the Nature of Peng (Ward-Off)

Master Chen Zhonghua’s explanation of the Eight Methods is deeply rooted in the concept of the “One Method,” from which all others are derived. He states, “There is only one method in Taiji. It is called peng. All the other seven are just positional variations of peng.”

This is not a mere technical point; it is an assertion about the fundamental state of the body and movement. He emphasizes: “Peng is not a technique. It is a state of your body. It is a quality of your movement. It is the foundation upon which everything else is built. Without Peng, the other seven methods do not exist.” This philosophical and physical unity is the core tenet of the Hong-Chen lineage.

Analytical Models: Lever, Wheel, and Sphere

To help students grasp the physical dynamics underpinning this unity, Master Chen frequently employs concrete, mechanical analogies—a practice inherited from Master Hong.

For the four cardinal methods (Peng, Lü, Ji, An), he uses simple machines to illustrate their interconnectedness: “This is a simple machine, a lever… When you pull this way, it’s Lü. When you push this way, it’s An or Ji. It’s the same machine, just working in a different direction.” This model demonstrates how the methods are merely different applications of the same underlying physical structure and energy.

To integrate the four corner methods (Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kao) with the core four, Master Chen introduces the spatial dimension: “Your power must be a sphere. Not a circle, a sphere. A circle is flat. A sphere is everywhere. Peng, Lü, Ji, An are on the main lines. But the opponent will not always push you straight. He will push from an angle. Your sphere must be able to turn on any axis. When it turns on a diagonal axis, that is Cai, Lie, Zhou, Kao. It is the same sphere, just turning differently.”

This powerful 3D Sphere model completes the systematization, illustrating that the entire arsenal of the Eight Methods is a cohesive, unitary system of whole-body motion and structural integrity, all revolving around the quality of Peng Jin.

Conclusion: A Legacy Secured Through Systematization

|

The relationship between Master Hong Junsheng and Master Chen Zhonghua represents the critical evolution of the Practical Method from profound insight to universal system. While Master Hong provided the original blueprint—an “engineering manual” for Taijiquan focused on physically verifiable mechanics—Master Chen established the definitive pedagogical framework for its transmission.

Master Chen’s contribution is a definitive amplification and systematization of his teacher’s work. He elevated Hong’s core rule into the explicit axiom of the “One Method,” providing the mechanical how behind the structural principle. |

|

His use of concrete, physics-based analogies (the Lever, Wheel, and 3D Sphere) is the ultimate expression of the system’s name: the Practical Method. By translating elusive internal concepts into verifiable, testable, and trainable mechanics, he fulfilled the practical intent of his teacher.

In essence, Master Hong established the principle of a structurally sound, effective martial art, and Master Chen provided the system for its widespread, unambiguous transmission. By developing comprehensive videos, class notes and workshops based on these mechanical models, Master Chen has demystified the Eight Methods, securing the legacy for future generations.