|

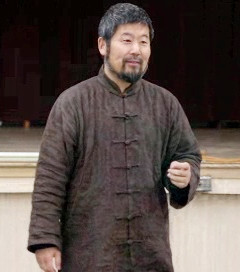

What is the true essence of Taijiquan? Master Chen answers this question not with a complex explanation, but by simplifying the Eight Methods (八法 Bā Fǎ)—the foundational building blocks of the art. While historical figures from Wang Zongyue to Yang Chengfu contributed vital interpretations, sometimes viewing the methods as specific techniques or esoteric energies, Master Chen follows his teacher, Master Hóng Jūnsheng, in revealing their deeper intent. He insists that the Bā Fǎ are not reactive postures but dynamic principles (原理)—universal concepts that govern the body’s structure, alignment, and energy flow in every moment. |

| This essay will illuminate how Master Chen’s direct, practical approach, taught in his 2014 Toronto Workshop and backed by the wisdom of Master Hong’s writings and the Taiji Classics, strips away centuries of technical formalism to reveal the clear, direct application of the Practical Method. | |

| (This article is based on the Eight Techniques mini-lesson filmed in 2014, Toronto, Canada.) |

|

The mini-lesson begins with a question: “What is the Eight Methods of Taijiquan?”

A seemingly simple question led Master Chen to unpack a profound concept—one that lies at the very heart of Taijiquan practice. Every serious Taiji enthusiast eventually encounters the idea of the Eight Methods (bā fǎ, 八法), also referred to as the “Eight Techniques.” These foundational energies— péng (掤), lǚ (捋), jǐ (挤), àn (按), cǎi (采), liè (挒), zhǒu (肘), kào (靠)—are not merely movements but expressions of internal force and strategic intent.

|

|

Introduction

|

The formative theory of Taijiquan was meticulously documented during a pivotal period from the mid-19th to early 20th century. This effort preserved an art traditionally transmitted through master-disciple relationships (师徒传承) and oral instruction (口傳心授). Historically, these methods are referenced in the Taiji classic Treatise on Taijiquan (《太极拳论》) , attributed to Wang Zongyue (王宗岳). In 1875, the renowned Yang stylist Yang Banhou (杨班侯) elaborated on these techniques in his manuscript Explaining Taiji Principles (《太极法说》) , framing them within the concept of the Thirteen Dynamics (十三势) , comprised of the Eight Gates (八门, bā mén) and Five Steps (五步, wǔ bù). |

| This theoretical foundation was then expanded into a practical framework for cultivation. In 1881, Lǐ Yìyú (李亦畬) published his book Li Yiyu’s Taijiquan Manual (《李亦畬太极拳谱》), which contains an important treatise, Essentials of Form, Push Hands, and Internal Work (《走架打手行功要言》). This work can be read as a direct development of the principles laid out in Wang Zongyue’s Taijiquan Classic, which describes Taiji as the interplay of Yin and Yang, the art of sticking and yielding, and the avoidance of double‑weighting. Wang articulated the philosophical and strategic core, explains the transformation of stillness and movement, the balance of emptiness and fullness, and the ideal of “four ounces deflecting a thousand pounds”. |

|

Lǐ extends these ideas into a systematic framework for practice. By mapping the Eight Methods to internal qualities cultivated through form, tested in push hands, and sustained by internal work, Lǐ operationalizes Wang’s abstract principles into tangible, trainable energies (劲, jìn). In doing so, his treatise serves as both a commentary and a practical manual, showing how the Classic’s yin–yang theory becomes embodied skill.

|

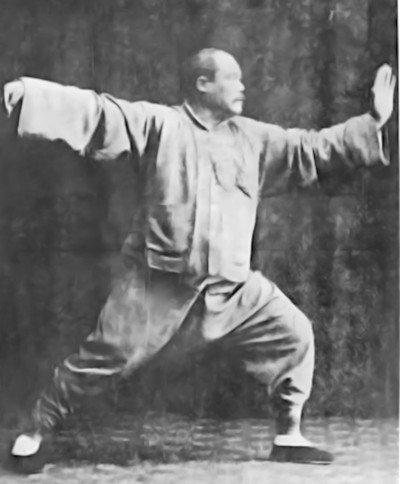

In the following decades, masters worked to both popularize and deepen the cosmological interpretation of these principles. In 1931, Yang Chengfu (杨澄甫) emphasized practical application in his book Methods of Applying Taiji Boxing (《太极拳使用法》), especially in the context of push hands (推手) training. In 1934, he published The Eight Methods Secret of Taijiquan (《太極拳八法秘訣》 ) in his book The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan ( 《太極拳體用全書》). This text was written to codify and explain the principles and techniques for a wider audience, moving beyond traditional secrecy. Yang emphasized that these methods are not merely techniques but expressions of internal energy (气), body alignment, and mental intent, stressing the importance of softness containing hardness—likening the ideal state to “a needle hidden in cotton” (绵里藏针). |

| Conversely, in 1933, Chen Xin (陈鑫), a master of Chen-style Taijiquan, offered a deeper cosmological interpretation in his seminal work Chen Style Taiji Boxing Illustrated (《陈氏太极拳图说》 ). He proposed that the eight methods represent energies with symbolic and metaphysical associations to the Eight Trigrams (八卦) of the Yijing (《易经》). Chen Xin also categorized the eight methods into main directions (主方向) and secondary directions (次方向), emphasizing their spatial and strategic significance. |

|

The period of intense textual codification from the late 19th to early 20th century preserved Taijiquan’s theory for future generations and provided unparalleled public access to once-secret knowledge. Yet, this democratization contained a profound paradox. Through time, widespread reinterpretation, and the loss of the intimate master-disciple context, the original meaning of these methods became diluted—often reduced to a set of superficial technical actions. Thus, even as Taijiquan soared in global popularity over the next fifty years, its profound martial foundations began to fade. The essence of the art became more esoteric not because it was hidden, but because its true intent was gradually separated from its practice.

|

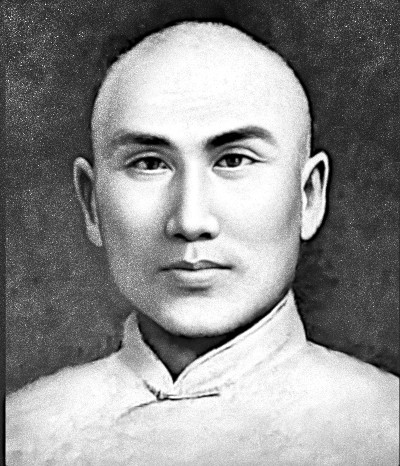

It was precisely against this backdrop of dilution that a direct corrective emerged in the late 20th century through the work of Master Hóng Jūnsheng (洪均生, 1907–1996), a direct disciple of the legendary Chén Fākē (陈发科). Master Hóng dedicated his life to a rigorous, logical, and practical reconstruction of the art. He famously summarized his philosophy with the axiom, “Gongfu and method are one and the same thing” (「功夫、方法,就是一样东西。」). |

This principle directly challenged the widespread separation of theory and practice in martial arts training. Master Hong argued that true skill (gongfu 功夫) and precise method (fangfa 方法) were two sides of the same coin: one could not be attained without the other, and any method was without value unless it produced a practical result (shiyong 实用). His life’s work was a quest to reunite the art’s profound theoretical principles with their authentic martial application, providing a clear path back to Taijiquan’s original essence. He codified this approach in his seminal book, Chen-Style Taijiquan Practical Method (《陈式太极拳实用拳法》).

Master Hóng’s work stands as the direct evolution and resolution of the earlier century’s efforts. Where the texts of Lǐ Yìyú and Yáng Chéngfū aimed to document and popularize, and Chén Xīn sought to provide cosmological depth, Master Hóng provided a practical, logical system. He effectively demystified Taijiquan, revealing it as a sophisticated science of body mechanics and energy transformation governed by a consistent internal logic. His Practical Method thus marked a significant evolution in modern Taijiquan transmission: it preserved the art’s profound martial essence while providing an unambiguous, accessible path for dedicated practitioners to achieve it, directly countering the dilution that had accompanied its spread.

Continuing this legacy, Master Hong’s student, Master Chen Zhonghua, reorients our understanding of the Eight Methods. He stresses that these are not merely fixed techniques (jìqiǎo, 技巧) but are, in fact, guiding principles (yuánlǐ, 原理). These principles represent fluid, universal concepts that transcend specific postures or measurable actions. Rather than being confined to mechanical responses, they are adaptable energies that should be applied across all aspects of Taijiquan practice.

By returning to the basics, Master Chen invites practitioners to explore the essence of each method—not just how it looks, but how it feels, flows, and transforms. In doing so, he restores the Eight Methods to their rightful place: as living principles that guide movement, intention, and internal development.

Master Chen’s mini-lesson on the Eight Methods opened with a concise, yet powerful declaration: “Yin-Yang split”. This two-word phrase became the central theme, as he masterfully demonstrated how this core concept informs each of the Eight Techniques. When a student sought further clarity, Master Chen didn’t just explain; he seamlessly bridged theory and practice by demonstrating a specific application for each method. He concluded by revealing a profound truth: “The eight taiji techniques are based on yin-yang split of different directions. The eight techniques are directions“. As a supplementary feature, the writings of Master Hong and his explanation have been added to each section to highlight his profound influence on our understanding of these techniques.

Part 1. Four Primary Energies (正劲)

Master Hóng Jūnsheng, building upon the rigorous foundation of the Chén family lineage, provided an essential analytical structure for the Eight Methods of Taijiquan by classifying them into two distinct categories of energy, or jìn (勁).

In the foundational chapter of his seminal work, Practical Method of Chen Style Taijiquan, he explicitly states this bifurcation:

“The Eight Jìn methods of Taijiquan can be divided into two groups: first, Peng, Lu, Jı, and An—these are the four primary energies; second, Cai, Lie, Zhou, and Kao—these are the four diagonal energies.”

(“太极拳的八门劲力可分为两组:一是掤、捋、挤、按这四正劲;二是採、挒、肘、靠这四隅劲。”)

This conceptual separation is not merely descriptive; it is the cornerstone of Master Hong’s systematic, “Practical Method” approach. By separating the Jìn into these two functional groups, he provides a clear framework for understanding their contrasting roles:

|

The first group, the Four Primary Energies (正勁 ), are also frequently referred to as the Four Straightforward Energies or the Four Cardinal Directions (四正). Master Hong classifies them as “ primary ” because they form the fundamental, continuous framework of interaction in Taijiquan, particularly in the cyclical practice of Push Hands (Tuī Shǒu). They are considered the core energies that deal with forward, backward, upward, and downward dynamics relative to the practitioner’s center, establishing the basic structural integrity before any specific technique is applied. This clear, analytical model is a hallmark of Master Hong’s work, distinguishing his systematic explanation from more generalized or esoteric narratives of the Eight Methods.

1. Peng (掤)

Peng (掤), most commonly translated as “Ward Off ,” is frequently described in mainstream practice as an upward and outward redirecting force, an “energetic shield.” This common notion, though capturing the external form, while this captures the basic external form, it risks reducing Peng to a mere reactive physical posture.

Master Hong profoundly refines and corrects this common view. He defines Peng not simply as a static posture or an attitude of expansion, but as the fundamental, outward-spiraling force that must permeate all techniques. Master Hong emphasized that Peng is

|

According to Master Hong:

|

“In Taijiquan, there must be Peng Jìn everywhere… Peng Jìn is a spiraling and rotating force… It is like the water of a great river, ever-flowing; the surface may be calm, but within there is tremendous power.”

(“太极拳处处都要有掤劲,……掤劲是缠绕旋转的劲,……如同江河之水,滔滔不绝,表面平静,内在却有巨大的力量。”) |

Peng Mini-Lesson

|

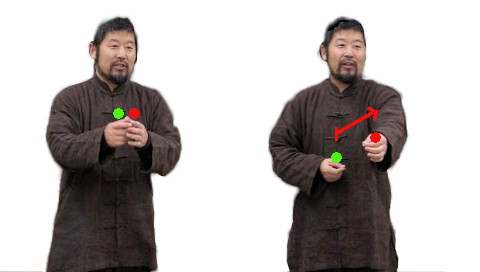

This sophisticated understanding of Peng as a dynamic, internal, and ever-present force is echoed in the teachings of Master Chen. He distills the essence even further by using a simple yet profound demonstration. He clasped his hands in front of his chest at about a half arm’s length, then separated them. As he moves his left hand forward, he simply states, “This method of separating Yin and Yang is called Péng (掤).” |

This action is illustrated in the Figure 01. A red dot marks his moving hand, and a green dot marks his stationary hand, showing their initial proximity and final separation. The red arrow indicates the forward movement of the hand away from the body, while the green dot highlights the hand that remains close to his body.

| Master Chen reminds his students that while the principle is applied differently in combat, they can demonstrate it with a partner in a fixed exercise. He instructs his students to place their hands on his sides at shoulder height. In response, Master Chen grasps the student’s wrists, establishing the initial position shown in the left section of Figure 02. In this diagram, a green dot marks a stationary point on the body, while a red dot indicates the initial anchor point. |

|

Master Chen then executes the action of Peng and asks, “Can you see that I [my body] never moved. I expanded this way [towards my opponent] as a Peng.” The right section of Figure 02 illustrates this action. The red arrow highlights the movement of the anchor (initially the red dot) as it moves away from the body’s stationary point (the green dot). It’s crucial to understand that Master Chen is not pushing his opponent away. Instead, the action is better described as the opponent pushing themselves away. A suitable analogy is a person pushing into a stationary rubber ball and then bouncing back. This is the practical application of Peng as a direct reaction to an incoming force.

2. Lu (捋)

Lǚ (捋), often translated as “Roll Back,” is commonly understood as a technique to absorb and neutralize an opponent’s force by guiding it away. Such conventional interpretations that focus on physical movements like adsorb and neutralize—accurately describes the external characteristics of Luˋ, it remains insufficient. This surface-level grasp fails to illuminate the profound internal mechanics at the technique’s core, neglecting the essential NeˋiJing (internal force) generation and coordination that truly define the method.

Master Hóng Jūnsheng provides a far more sophisticated interpretation of Lu (Rollback), moving beyond simple neutralization to define it as the complementary opposite of Peˊng (Ward Off). For Master Hong, Lu is not merely a yielding or drawing-in; it’s a precise, spiraling withdrawal that fundamentally transforms the opponent’s forward momentum.

This technique demands that one adheres to the opponent’s attack, subtly guiding their force past its intended target to break their structure (破势, pò shì), rendering them vulnerable. It requires impeccable timing and coordination with the torso’s turning to ensure one never meets the opponent’s force with opposing strength. Master Hong stresses this profound adherence and guiding principle:

|

“Lu is to follow the opponent’s incoming force and guide it diagonally to one’s own side… causing their power to fall into emptiness, and subsequently lose their balance… It requires ‘sacrificing oneself to follow the opponent‘ (舍己从人, shě jǐ cóng rén), following the path of their Jin.”

(“捋是顺其来势,向自身斜侧方牵引,……使其力量落空,进而失重。……要舍己从人,顺其劲路。”) |

Effectively, Master Hong’s Lu is a master strategy for leading, emptying, and destabilizing, achieved through self-sacrifice and absolute adherence to the opponent’s Jin.

Lu Mini-Lesson

|

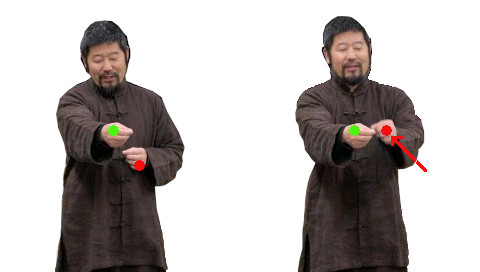

With simple, profound elegance, Master Chen demonstrates the Lu (Rollback) principle. He holds his hands clasped a half-arm’s length from his chest, then clearly and precisely executes the separation. He draws his left hand backward in the rollback movement, while the right hand remains fixed in space. “When you split Yin and Yang in this way, it’s Lu.” he explains, highlighting the precise, contrasting action of the hands. |

The accompanying Figure 03 clearly illustrates this technique’s physical metaphor. The red dot marks the hand executing the backward Rollback motion (Lu), while the green dot denotes the stationary, rooted hand. The red arrow visually reinforces the hand’s movement toward the body. Together, this contrasting action—the one hand retreating, the other remaining fixed—highlights the essential separation and spiraling quality of Lu.

| Master Chen began his demonstration of the Lu (Rollback) technique by engaging with a student. He instructed his student to attempt to seize him with two outstretched hands. As the student moved in, Master Chen fluidly intercepted the attempt by securing a hold on the student’s wrists. This initial, foundational position is precisely illustrated in Figure 04. |

|

Master Chen then used this moment to introduce a critical concept. He explained, “This time, I made a point here,” gesturing toward a specific location on the student’s back, which is denoted by the green dot in Figure 04. He continued, “This [dot on the back] does not move. So I locked him on his back [at that point], establishing an immovable anchor.” The red dot, by contrast, represents the anchor point of Master Chen’s grab—the leverage where his own action begins.

Instead of pulling, Master Chen then initiated the Lu action: he stretched the grabbed wrists away from that imaginary, fixed point on the student’s back. This vector of force and extension is visually represented by the red arrow in Figure 04. The student immediately reacted to this unique separation of force, their structure becoming compromised.

Master Chen concluded, “And this is Lu here.” He then provided a crucial reminder and contrast: “But it’s different from doing this,” simultaneously contrasting the subtle Taiji technique with a common, direct pull. He clarified that a typical pull relies on direct, muscular force—a contest of strength the student could easily resist. The Taiji Lu technique, however, is based on the universal principle of Yin-Yang separation and yielding, not brute force.

Master Chen summarized the key operational principle of Lu: “I imagined the back [of my opponent] never moved, and I extended it [my hold] away from this stationary point.” He concluded definitively, “That’s Lu.” emphasizing the central role of separating two distinct points—a rooted anchor and an extending force—to unbalance the opponent.

3. Ji (挤)

Jǐ (擠), traditionally understood as “Press” or “Squeeze” refers to techniques that apply focused forward pressure, typically using both hands in a converging, enveloping, or compacting motion. This action channels power into a unified direction, relying on focused energy rather than brute force.

However, for Master Hong Junsheng, the characterization of Jǐ shifts significantly. He views Jı not as an application of forward pressure, but as a squeezing force where both arms converge like a wedge to concentrate energy and take up space along the opponent’s centerline. For Master Hong, Jı is a compact, focused application of force that follows immediately after a successful Lu (Rollback). It is applied to the opponent’s body or arm once their structure has been compromised. According to Master Hong:

|

“After leading the opponent in with Lǚ and they begin to retreat or resist, Jǐ is applied. It often involves using one hand to press the opponent’s arm against one’s own forearm or body, and then emitting power forward along that consolidated line of force. It is short, explosive, and does not allow the opponent space to recover.”

(“挤是在捋之后,对方有回抽之意,我随即合劲前挤。……力点集中,短促有力,如钉入木。”) |

Effectively, Master Hong’s Jı is a compact, focused application of force applied the moment the opponent’s structure is compromised and they begin to retreat or resist.

Ji Mini-Lesson

|

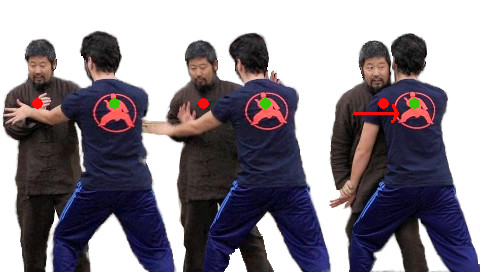

Master Chen demonstrates the Jǐ (Press) principle with a simple two-hand movement. Starting with his hands separated a half-arm’s length from his chest, he moves his left hand forward toward his stationary right hand.”When you split Yin and Yang in this way, it’s Ji.” he explains. |

This action, illustrated in Figure 05, physically represents the principle of Press. The red dot marks the moving left hand, and the green dot indicates the stationary right hand. The red arrow shows the forward movement. This simple separation and movement reveal the essential nature of Ji: taking up space by pressing one point toward a stationary one.

| Master Chen began his demonstration of the Jı (Press) technique by having a student initiate an attack. The student grasped Master Chen’s shoulders with both hands. Master Chen smoothly countered this action by parrying the student’s wrists, securing the initial control. This starting configuration is precisely illustrated in Figure 06. |

|

Master Chen then articulated the core concept of the technique, explaining, “[The technique of] Jıˇ is [as follows.] This [a point on my opponent] does not move.” This immovable anchor he refers to is represented by a green dot on the student’s back in Figure 06. The red dot, by contrast, represents the actively moving position of Master Chen’s body. He continued, “I pull myself into it [that stationary point]. Can you see this is a Jıˇ.” In this application, Jı is executed by using the opponent’s structure as a fixed point and driving one’s own body into the space.

Master Chen provided a second demonstration to further clarify the principle. In this scenario, the student attempted to seize Master Chen’s wrists. Master Chen instantly countered by seizing the student’s wrist instead, turning the attack into an opportunity. Stating the action clearly, he explained, “You see on that here [I have countered his grab by holding his wrist]. I used him [my hold on his wrist] to pull myself in [to his body, in the space between his two arms]…”

Master Chen emphasized that the key to effective Jı is not a muscular push, but the strategic use of space: “[By taking up space between the contact point and my opponent,] That is [the method of] Jı.” This demonstrates Jı as the act of pressuring the opponent by occupying and collapsing the space in their structure, driven by the practitioner’s body weight and movement toward a fixed point.

4. An (按)

Àn (按), a Chinese martial arts term, is often simply translated as “push” or “press” in English, leading to a common but limited definition: a direct forward shove, typically with the palms, to displace an opponent.

However, Master Hong argues this definition is incomplete, failing to capture the unique internal dynamics of the action. He offers a more nuanced interpretation, defining Àn as a sinking downward press driven by internal rooting, intended to collapse the opponent’s balance.

Master Hong elaborates on the power generation, famously stating:

|

“Àn Jin is like a wave; first sink down to store energy, then surge forward and upward… It has the momentum of sinking and pushing forward, causing the opponent’s root to float up and them to fall out.”

(“按劲似波浪,先向下沉蓄,再向前上涌起,……有下沉前推之势,使彼根浮起而跌出。”) |

He stressed that Àn is far more than a simple two-handed shove. It is a sophisticated technique involving the whole body. The action requires the body weight to sink (沉,cheˊn) combined with a forward expansion. The power originates from the feet, is directed by the waist, and is expressed through the palms. This force is often delivered in a slight downward arc to press the opponent’s arms against their own body, effectively disrupting their root and causing them to fall.

An Mini-Lesson

|

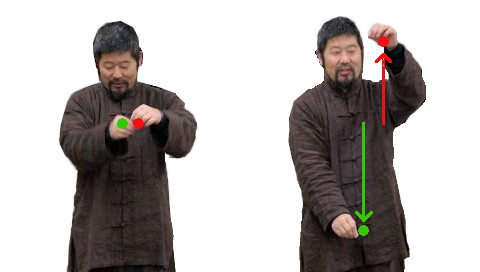

Master Chen illustrates the An (Push) principle with a simple two-hand movement. He begins with his hands at chest level, then executes the move: his left hand sweeps upward as his right hand simultaneously presses downward.

Master Chen succinctly defines this action, stating, “When you split Yin and Yang in this way, it’s An.” |

This simple, opposing motion, shown in Figure 07, is the physical embodiment of Push. The diagram clarifies this: a red dot highlights the upward path of the left hand, and a green dot charts the downward path of the right. The colored arrows detail the exact trajectory of each hand. This vertical separation and simultaneous, contrary movement is the core essence of An.

Master Chen then demonstrates this fundamental technique with his student to illustrate its practical application. The student initiates the engagement, applying pressure by firmly grasping Master Chen’s shoulder with one hand and simultaneously exerting a pushing force on Master Chen’s hip with their other hand. This creates a classic scenario of an opponent attempting to control and unbalance.

| Master Chen’s immediate response is precise and defensive: he secures a grip on the back of his student’s neck with one hand and simultaneously intercepts the student’s push on his hip by controlling the student’s wrist with his other hand. This initial, locked position, forming the anchor for the subsequent movement, is clearly shown in the right panel of Figure 08. The red and green dots, both labeled ‘1’, denote these initial anchor points—the fixed points of contact where the forces are held in balance. |

|

From this locked position, Master Chen momentarily remains still before initiating the first action, the technique of Ji (often translated as pressing or squeezing). This action is a powerful, inward movement designed to aggressively take up space between him and his student, eliminating any slack or gap. This inward, compressive pressure is visually represented in the middle panel of Figure 08. The red dot labeled ‘1’ and the red arrow labeled ‘1’ highlight this strategic movement of Master Chen’s anchor point as it drives towards the stationary green anchor point on the student’s back, compressing the space between them.

Master Chen elaborates on this concept: “An is when you are pushing. I’m in here [by performing the technique of] Ji here [to eliminate the space between us].” This confirms that Ji is the crucial preparatory step that establishes the necessary close-quarters control for the next phase.

Master Chen continues: “At the end of the Ji here. I change direction. It [the opponent’s body] goes that way. [That is an example of a combined technique of Ji followed by An.]” The final, dynamic action of this combined technique, An (meaning pushing downward), is shown in the last panel of Figure 07 and results in the student powerfully falling down or being thrown.

Critically, after the compressive action of Ji, two new anchor points are utilized, now labeled with the number ‘2’. The stationary anchor, shown as a green dot labeled ‘2’, is now located on Master Chen’s body, providing a solid base. The active anchor on the student’s body is shown in red with the same label.

The An technique is then executed with a complex, unbalancing movement: first, a vertical, sinking movement to disrupt the student’s balance, followed by a separation away from the stationary anchor on Master Chen’s body, effectively leveraging and driving the student to the ground. This outward and downward directional force is labeled with a red arrow line labeled ‘2’.

Master Chen concludes, summarizing the overwhelming nature of the finishing technique: “I use your whole body [in this technique of An].” This emphasizes that An uses the established anchors to project the student’s entire mass, rather than just isolated limbs.

Master Chen provided an alternative, more focused example to illustrate the principle of An, clarifying that its application doesn’t always require controlling the opponent’s entire body.

He began by stating the core idea: “[Rather than using the whole body for the An technique,] I can use one spot [on the opponent’s body to demonstrate this technique].” The scenario is initiated with the student applying pressure: “When you are here. [The opponent’s hand is pushed on my chest.]”

|

The student fully engages by pushing Master Chen’s chest with both hands, a common forceful attack shown in Figure 08. Master Chen’s response is swift and localized: he uses one of his hands to push downward on the student’s wrists—a sharp, sudden motion that is perpendicular to the horizontal line of the student’s aggressive push. He then confirms the result: “Can you see that’s An.” Due to the sudden redirection of force, the student is instantly unbalanced and stumbles forward. This vertical, downward movement applied to the wrist is clearly depicted in Figure 08 by the red arrow, which shows the trajectory of Master Chen’s hand. |

Master Chen then provides a precise explanation of the technique’s underlying geometric concept: “An is to separate according to a 90-degree direction so when you are pushing.” This means the effective force of An is applied at a right angle to the opponent’s original line of attack or pressure, instantly collapsing their structure.

To emphasize the distinction between simple movement and the technique of An, the student pushes Master Chen on the chest again. Master Chen responds by wiggling his torso in a horizontal, non-committal fashion around the point of contact, asking: “So this is no An, right? no An? But see like here…”

He then immediately executes the technique again: Master Chen uses his hand to apply a sharp, vertical press directly down on the student’s wrist. This downward An force, executed perpendicular to the horizontal push, again causes the student to stumble and break their posture forward, proving that the vector of force—the 90-degree separation—is one definitive characteristic of An.