|

Master Hong emphasizes that the upper torso’s core requirement is an upright, suspended head—encapsulated in the classical axiom “虚领顶劲” (“suspend the collar to lift the energy”). In his book, “Chen Style Taijiquan Practical Method V1: Theory” , he reinforces this idea by quoting the Thirteen Postures Song (《十三势行功总歌》): “the whole body is light, and the head is suspended” (“满身轻利,顶头悬” ). Although “push” and “suspend” differ in wording, Hong clarifies that both demand a lifted crown, as if the body were hung by a rope from the baihui point, echoing Chen Xin’s metaphor – ‘ A subtle chin tuck then allows the head to self-balance atop a straight spine, naturally aligning the neck ‘ (如同用绳子从头顶百会穴将全身向上悬起似的). This principle, praised in Wang Zongyue’s Tai Chi Theory (王宗岳 《太极拳论》) and is ranked first among the “Ten Essentials” in Yang style Tai Chi (杨派太极拳列为“十要”之首). |

| What does this principle truly mean in practice? Master Chen brings clarity by demonstrating it through mechanical models, stripping away abstract interpretations. As he puts it, ‘Ignore… the so-called Taiji concept, do this…’ and, drawing from Master Hong’s teachings, ‘Once you follow this rigid mechanical model… you get it.’ His approach translates traditional wisdom into tangible, repeatable technique. | |

| (This is an edited transcript of the Suspended Head filmed in Winter, 2010, Edmonton, Canada.) |

|

|

According to Master Chen “ Suspended head is a Taiji concept that refers to maintaining an upright spine at all times. When practiced correctly, the head feels as if it’s gently lifted—either pulled upward from above or supported from underneath—creating a sense of lightness and alignment.”

|

1. Principle of suspended head

|

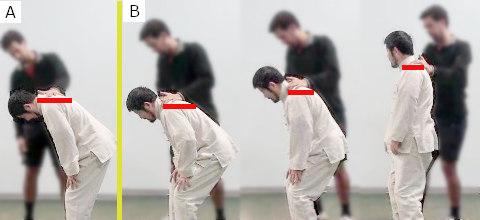

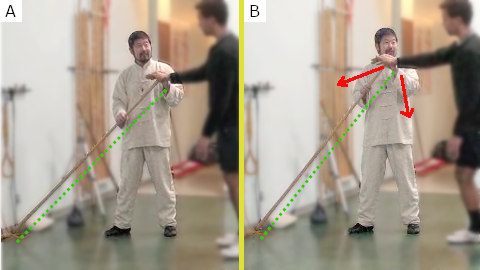

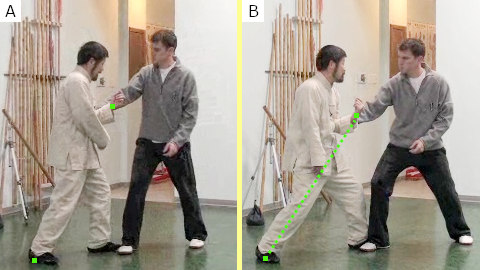

Master Chen begins. “Do something here.I’ll go like this here.” Master Chen then bends over, as if preparing to sit down in a chair. He suggests, “Let’s experiment. Put your hands here—behind my neck. Push me down right at that point. Use both hands, be strong. I’m going to fight you.” |

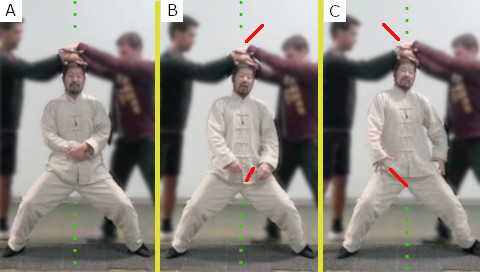

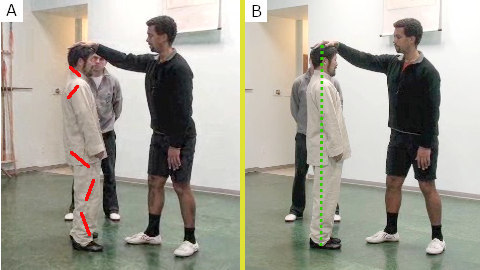

As his student applies pressure to his neck, Master Chen tries to lift his head up. This moment is illustrated in Figure 01A, where the red lines show the resistance and the opposing forces at play.

“Can you feel that fight?” he asks. “Can you make sure you win? Yeah, okay. You feel that? You’re winning, right? You feel that?”

Then, Master Chen shifts his approach and performs a Taiji movement.

“Now, I’ll feel this here. Try again. Use whatever method you want. Okay? You feel.”

This time, Master Chen is able to stand up. He repeats the demonstration, and the result is shown again in Figure 01B, with the red line indicating the resistance.

|

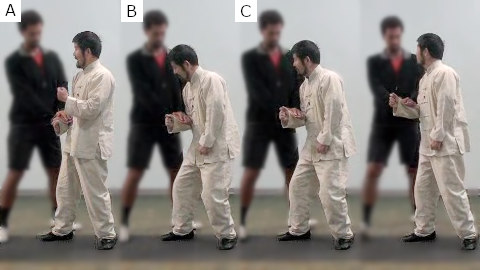

Master Chen then shifts the scenario and introduces a second example. He instructs his student to use both hands to hold his right arm and push. This setup is shown in Figure 02A. Master Chen begins:

“Now, do it here—use both of your hands to hold my arm. Push me down. Yeah, yeah, push me down. Can you feel you’re winning? You feel the power, right? It doesn’t mean you have to physically win, but you feel like you’re engaged. You’re engaged. Your power is valid.” |

|

Then, Master Chen performs a movement based on Taiji principles and, once again, is able to stand up. This moment is captured in Figure 02B, with the red line indicating the resistance. Master Chen appears to overcome his student’s grip on his arm.

He explains: “So, in the second move, where I responded using Taiji principles, your power is no longer valid. It’s not that you don’t have enough power. It’s that the kind of power you’re using on my arm doesn’t work in this context.”

Master Chen then asks his student:“Did you experience that? Don’t ask why yet.”

The student replies that he did experience it.

|

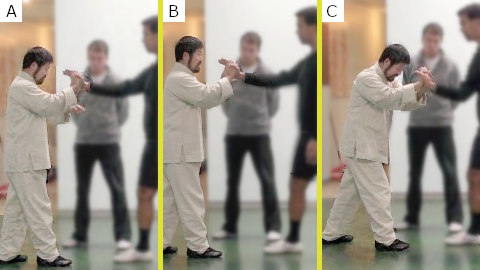

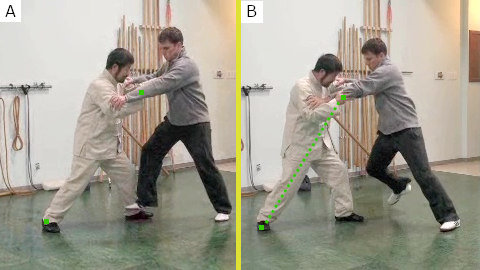

Master Chen sets up the third example. He instructs his student to use both hands to push against his right shoulder. This position is illustrated in Figure 03A. He begins to explain: “Let’s see here, with both of your hands on my shoulder. Yeah. Push me down with your hands. Okay? Can you feel there’s a fight? Right?”

Master Chen then performs a movement based on Taiji principles and smoothly moves away from his student’s grip. This action is shown in Figure 03B. |

He concludes: “But see—when I act according to Taiji principles—there’s no fight. You can’t fight it.” Master Chen then turns to his student and asks: “Is that experience clear?”

The student replies: “In the first example, I felt like there was some back and forth. I could sense where you were, and I could push you down—yeah. But in the second example, it felt like I just had to get out of the way.”

Master Chen begins to explain the difference between normal movement and Taiji movement:

“First of all, this is very difficult for you to clearly understand. The reason is, even when I do it wrong, it still looks like a fair fight. As a martial artist, I have physical power. So even if my technique is off, I’m still a strong person—believe it or not—and I can hold my own in a fight.

Now, imagine I didn’t have that physical power. The way I move—if done properly—would make it impossible for you to engage me. If I truly had no physical strength, the difference would be obvious. But right now, it’s not clear, because even when I perform Taiji incorrectly, I can still fight. At my age, with my training, I still carry power—though it’s the wrong kind of power. I haven’t completely let go of my physical strength. I have both: the Taiji method and residual physical power.

That’s why I need to explain this very carefully. The demonstration alone doesn’t make it obvious. When I do it wrong, you still think I’m doing well—because that leftover power makes it look effective. But from the Taiji perspective, that residual power is actually not a good thing.”

The student asks: “There’s still a clear difference, though. When you do it the wrong way, I feel power, but it’s like I’m pushing against something. But with the second way, I don’t feel like I’m pushing against anything at all.”

Master Chen continues: “So, what I want to bring out through this experiment, what I want to talk about, is a concept in Tai Chi called the ‘ suspended head ’. This is a vital concept—one of the top principles in Tai Chi. Most people who come into Tai Chi already have some experience with this theory, this concept, or at least some level of understanding. So I’m not going to go into the very basics. Instead, I’ll directly show you what really governs this type of action.

It’s called a principle because we use this particular point [the top of the head] to demonstrate it. But in reality, if it’s a principle, it means it’s omnipresent—it applies to every part of your body and every action. That’s why it’s a principle, not a technique. It’s not only here [on top of your head]. Every principle is demonstrated through one body part. We choose one area to highlight it. For example, some rotations are demonstrated through the waist. This one is called the suspended head.

There are several traditional explanations or descriptions of it. One traditional term is Xū lǐng dǐng jìn (虛領挺勁), which roughly translates to “empty the collar and extend the energy upward” Because of the variation in verbal descriptions, there are many interpretations.

The ‘empty collar’ description leads people to practice this [type of movement: sticking the head forward and then move it back and forth]. And [this type of exercise encourages the posture which] sticks your neck onto the back of your collar, tucks the chin in, and pokes the head upward. That gives a clear visual and physical movement to imitate, helping to carry out the principle of Xū lǐng dǐng jìn—the suspended head.But overall, we can set all of that aside and focus on what we are actually doing.”

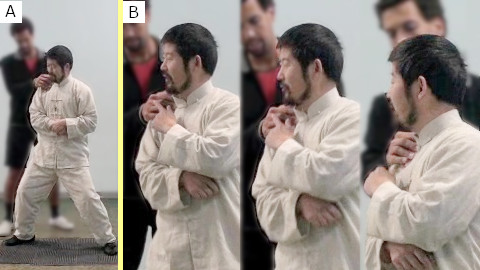

Master Chen revisits the principle of the suspended head as taught in Practical Method training. He begins by stating, “There are several things that are actually done under this principle here.” Standing in a ready posture with feet parallel and spaced shoulder-and-a-half width apart, Master Chen demonstrates the concept.

|

He calls over a student and instructs, “Come back here. Put your hand on my head and push me [press down on my head]. [Use both] hands to be stronger.” He then asks another student to do the same, placing both hands on his head. This initial setup is illustrated in Figure 04A.

Master Chen continues, “I’ll give you some variations so you can feel the difference. Right now, I’m centered. You push harder, you see. You’re not doing anything. Like, I don’t care. But if I’m slightly off, you push, you see. Now you engage with my body.” |

|

This variation is shown in Figure 04B. The red line highlights the body’s reaction if the push on the head is off.

He adds, “And now, I’m a little off here [towards my right]. Now see, look, I’m in big trouble.” This position is captured in Figure 04C. The red line showing the problem that occur when the head is not centered.

Master Chen elaborates, “You see, every time I vary—just move my body a little—you can feel whether you’re able to engage. You can sense that you have power. But sometimes, that power doesn’t go anywhere. There are moments when your power is like water—it finds a hole and flows through. And then there are times when that water just sits there, not moving at all. That’s why I vary a little bit—so you can feel it.”

Master Chen revisits the concept once more. He begins, “Now let’s do it again.” Standing in a neutral posture, he addresses his student, “Can you see you got something here [with your hands on top of my head], right?”

He then adjusts his stance in alignment with Taiji principles and continues, “But now, see, look, you got nothing.” To illustrate this shift, Master Chen begins moving his arms and body while keeping his head in the correct position.

He points out, “See, look, I’m doing [something with my hands or body].” The student confirms that, in this position, they do not feel any movement through their hands placed on Master Chen’s head.

Master Chen concludes, “Whatever you want to do, it doesn’t really matter. Why? Well, there are plenty of ways to explain it. But no matter how you try to explain, it always comes back to the same principle.”

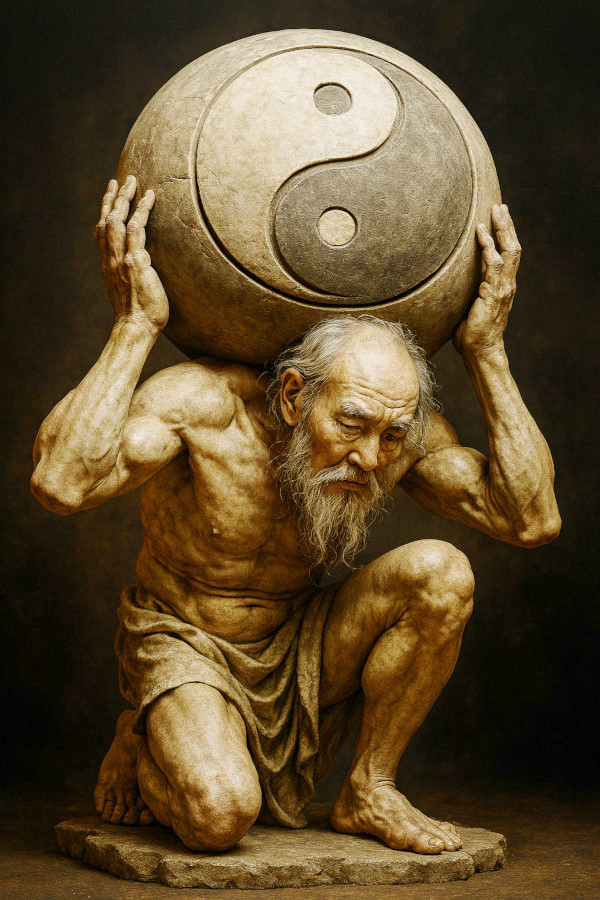

Master Chen uses a physical analog model to help explain this difficult Taiji concept. He shares why he relies on such a model: “… use our devices. And remember, we’re applying different principles here, but in Taiji, everything ultimately comes down to the same thing. So at the very beginning, if we tell you the real answer—that everything goes or comes to the same—you might think, no, that can’t be right. We’re talking about the suspended head. Why is he circling back to the same idea again? Because it is. Everything is just Yin and Yang .”

2. Rubber Band Model

|

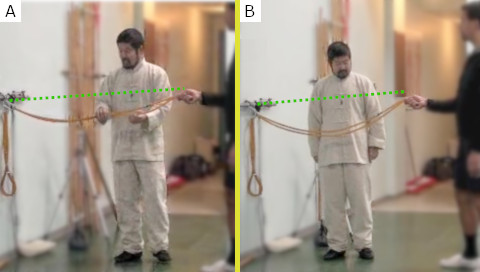

Master Chen uses a rubber band model to explain this concept. He attaches a rubber band with a carabiner to the wall and instructs one of his students to hold the other end. Initially, there is a noticeable slack between the two ends of the rubber band. This starting position is shown in Figure 05A. Master Chen explains, “So here, if you go like this here [hold one end of the rubber band]. There is no way that your hand connects to the wall or in this case, this rod [where one end of the rubber band is attached] when it [the band] is like this [soft without tension].” |

He adds, “When there is slack . So we use one word in this case in relation to this rubber cord. We call it slack. Another way of ignoring the property of this rubber cord and we call it ‘ something went outside of that line [that connects the two ends]’.”

Master Chen then stops supporting the rubber band in the middle, allowing it to drop and hang naturally. At this point, the rubber band becomes a simple physics problem: the slack band hanging between two anchor points forms a catenary curve, a smooth and symmetrical shape caused by gravity acting on the band’s weight. It dips lowest in the center and rises toward the anchors. Although the curve resembles a parabola, it is not one; it is steeper near the ends and flatter in the middle. Tension is greatest at the anchor points and lowest at the center. The shape of the curve depends on the weight of the band and the distance between the anchors. This situation is shown in Figure 05B, with the rubber band forming the resulting catenary curve and a dashed green line represents the virtual connection between the two ends.

Master Chen interprets this physical model from a Taiji perspective. “Because when it’s like this [there is a catenary curve], there is a straight [virtual] line here [that connects the two ends].” Master Chen adds, “Yeah. But the cord is not in that [virtual] line.”

| Master Chen then introduces the initial challenge presented by this physical model, asking his student to assist with the demonstration. He explains, “Let’s try to make the cord go [map] onto that [virtual] line.” Master Chen lifts sections of the rubber band and instructs his student to do the same. This action is illustrated in Figure 06A. The added red lines in Figure 06A highlight how the rubber band sags between each held point. |

|

Master Chen continues, “And how many hands do we need to make the cord go on this line? Too many. At least one million, right? Yeah. Because I did this here [lift the rubber band at this point], this [other point] didn’t listen [and drops down]. I do this [lift that point], this [other point] didn’t listen [and move away from the line]. Now I move here [to another position and support the band], this [another point] refused to listen [and drops away from the virtual line].” Figure 06B shows the difficulty of mapping the rubber band onto the virtual line.

Master Chen explains the significance of this example. “What I’m trying to demonstrate is that everything has a method. We understand the [the basic] principle: this [rubber band] has to be on the [virtual] line [in order for the two ends to be connected]. But using this method [of holding and moving the rubber band onto the virtual line], it won’t help. So now there is a method that relates to the property of this rubber.”

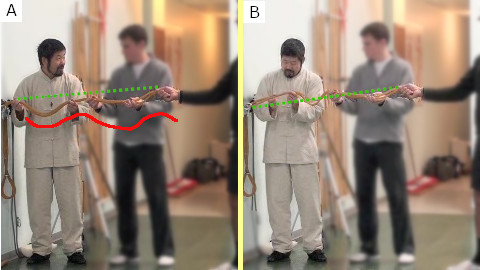

Master Chen introduces his method. He tells his student to continue holding the rubber band and instructs, “You stay on the [virtual] line [that connects the anchor on the wall and the end point on your hand].”

|

He continues guiding the student, “Your eyes look at the line here. Don’t move [the hand holding the band]. Lower your head until your eyes are here [on the same level as the hand].”

The student follows the instructions and lowers his stance until his eyes align with his hand. Master Chen then asks, “Can you see that line? [from the end of the hand you are holding to the other end anchor on the wall.]” This moment is illustrated in Figure 07A, with a green dashed line highlighting the [virtual] line. |

He continues, “Now don’t deviate and pull your hand with your eyes on the [virtual] line. Pull [along this line]. Pull.” The student follows Master Chen’s instructions, and the slack in the rubber band begins to reduce. This result is shown in Figure 07B with the rubber band now matching the green dash line.

Master Chen explains, “That’s it. See, that move, can you see there’s only one hand? You did not need one million hands. The end result is your cord is the line. It merges into that line.”

Master Chen emphasizes the importance of physically demonstrating theoretical concepts. “So this is very, very vital because I personally assume that everybody, after at least one week into Taiji, understands the theory. But do you have a method to carry it out?”

He revisits the initial approach of holding the rubber band and comments, “If your method is… go back again [to the previous method]. Try to stay on the line like this [by holding the rubber band onto the virtual line]. You can do this [wrong method] for 30 years, and in the end you will say, well, somehow the teacher is not telling me the secret. But actually, the secret of staying on the line was told to you the first day. You [just] did not have a method to do it.”

He continues, “So the method is very simple by doing this [stretching the rubber cord]. So this here [rubber band connecting two point], when it [this band] is tight. This is called the suspended head.”

Master Chen then applies the mechanical rubber band model to the problem of Taiji movement. He begins, “So in this action here [stretching the rubber band]. The suspended head analogy is [the end point of the rubber band attached to the wall] this is the foot, this [end point of the rubber band held with your hand] is the head. By the time you stretch everything out here [between your head and the foot] with no indentations, this [head] connects to here [foot]. You can feel it, right?”

Master Chen stretches the rubber band, demonstrating that the action applied to the end held in the hand can be felt at the fixed end on the wall. He then compares the stretched band to a slack one. He states, “But now when you are here [when the band is not stretched] and you do this [move the end that you are holding], you see this [held end] did not connect to that [end that is fixed onto the wall]. [Moving the held end point] It did something [for example, the slack band moves in the middle but there is no corresponding action at the other end point].”

Master Chen concludes, “These two contrasting cases show that when the band is stretched, a connection is created. When there is slack, there is no connection.”

Master Chen then explains the importance of connection. He states, “And without connection, we introduce another assumption. But the better approach is, let’s say, to treat it as a definition. Because when you call it an assumption, the student will argue, will present their own point of view. No point of view.”

Master Chen points to the stretched elastic band and offers a definition of connection. He states, “ When it’s connected, it has power.” He then points to a slack rubber band and concludes, “ When it’s not connected, it doesn’t have power.”

Master Chen summarizes, “So let’s not argue about that. Just say that’s the way it is.”

Master Chen then reminds his students, “So you have to connect. But then, of course, how do you connect? What does it mean to connect? Those you can define, because your definition will match mine—there’s only one way to connect. There are many visual things you can observe. But [the underlying truth is] if it’s connected, then it’s connected.”

3. Stick Model

Master Chen introduces another model to explain connection. He begins, “So this [rubber band model] is one way of looking at that connection. Now we use the same [stick model and bring it] back again [to explain another way of connecting].”

|

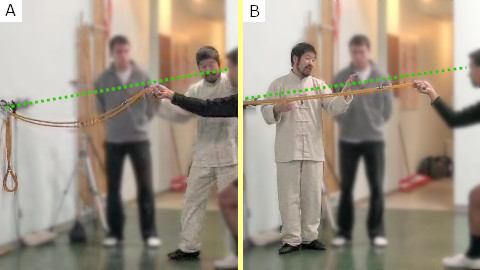

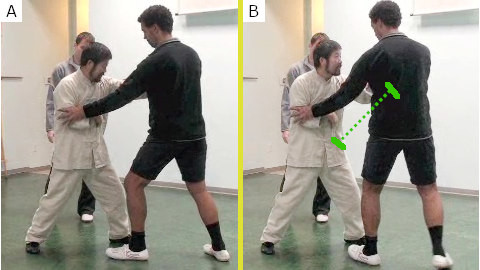

Master Chen holds a stick and places one end at the joint between the floor and the wall. He leans the stick at a 45-degree angle against the wall and instructs one of his students to hold the other end. He tells the student, “Here, yeah, grab it [the stick] here [at one end of the stick]. So push.” As soon as the student push on the stick, Master Chen exclaimed. “They’re already done, [the two ends are] connected.” This action is shown in Figure 08A. |

Master Chen then says, “Now push again. So your push, keep pushing.” While the student continues to push into the stick, Master Chen moves the stick. He explains, “Your push here [into the stick but the stick is moving], the energy leaked out into space. So this is what in Taiji is called ‘neutralize, to dissolve‘.” This action is shown in Figure 08B, with the red lines indicating the movement of the stick.

Master Chen reminds his student, “But it’s absolutely not a process called ‘absorbing’. You don’t absorb. So the stick never absorbed your energy. By doing this [moving one end of the stick], your energy going this way [not directly onto the point on the floor] went into space. It [energy] is all gone. It’s not a process of absorbing and then releasing it. It’s that it’s all gone. So it’s very important. Whatever this is, how to describe it, ignore it, just feel it. Your energy is gone.”

Master Chen concludes, “So now, if you do not allow that sway, push [into the stick]. The energy travels to the corner, onto that floor. So when your energy connects [from one end of the stick] to that here [corner], this becomes a [model for] suspended head.”

Master Chen summarized the analogy models and provide more details as follows: “So there are two ways to suspend it. One is a stretch. One is a squeeze. Push is a squeeze. [The action of the stick model can be described as] you pushing toward that definite spot that does not deviate. In this case [of the stick model], I use the word squeeze [rather than the word push] because when you say push, you are only describing this [one] action [of exerting force on one end of the stick]. [This term push] does not include that one [the anchor on the floor]. So now this push [in one end of the stick model] is only [valid] in relation to that non-moving spot. If you push that way [in a direction that is not on the non-moving spot], that [properties of the] suspended head is not there. Even when we say squeeze, it might not be correct. So the more important thing is your push must have a definite direction. The direction has to be exactly [on] that fixed spot.”

4. Connection

A student asked, “In relation to the body, the top would be the head. … The bottom would be… what?”

Master Chen answered, “The floor. All the way down to the feet. Wherever the direction is, you have to push into a direction that is solid on the floor.

|

Master Chen provides a demonstration of this idea with the help of his student. He tells his student, “So give me your hand.” The student extends his hand at shoulder level. Master Chen pushes on the hand. This is shown in Figure 09A.

Master Chen explains, “So here, my job is using this angle to have a solid connection with the floor.” He points to his student’s front foot and continues pushing the hand. The student’s arm moves in response. Master Chen comments, “This is not a solid connection.” This is illustrated in Figure 09B. |

He then explains the proper Taiji procedure to connect the push to the ground. “But while doing this [pushing your hand] here, see, I caught a little bit of your shoulder and then squeezed the shoulder down [until I can reach the floor]. Can you feel?” Master Chen confirms that the push is now felt through the front foot.

He elaborates, “I’m looking for that solid connection [your hand and your foot].” Master Chen reminds his student that this connection is highly sensitive to positioning and requires precision. He demonstrates, “If you turn it [the hand], see, my connection is not solid on the floor [any more].”

Master Chen then describes the continuous process of adjustment needed to maintain this solid connection. He continues, “So when you do that again, see, can you see I went back to the floor? And you see, look, it’s on the floor again. So you tilt [your hand] to find a solid connection onto the floor. So you can’t specify exactly where, it just has to be a part that aims solidly on the floor.”

Figure 09C illustrates how subtle the movement must be in order for Master Chen to connect with his student according to Taiji principles.

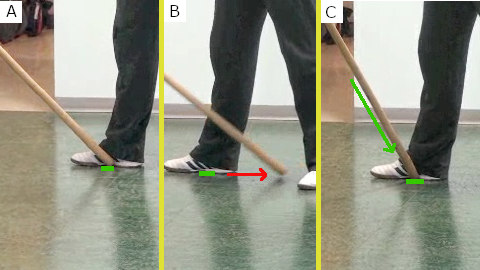

| Master Chen picks up the stick once more to demonstrate the concept of connection. He presses the stick against the ground, but it simply slides around due to the absence of an anchor. To stop this movement, Master Chen explains, “So I have to find a spot. So he is there.” The stick is now held in place by his student’s foot. This is illustrated in Figure 10A, where the green line highlights the anchor point. |

|

He continues, “Now this is why we always talk about connections. He’s there, but if I do it like this.” Master Chen then pushes the stick at an angle, causing it to slide away. This motion is represented by a red arrow. He explains, “Can you see? It [the connection] is not solid.”

Adjusting the angle, Master Chen pushes again and describes, “But if I go at this angle, it [the connection] is solid.” Figure 10C shows this scenario, with a green arrow indicating that the force is now properly directed toward the anchor.

Master Chen elaborates further, “So these things [such as placement and direction] are very important. [In this example,] Although the foot is the same, [it] provides an anchor. But if I go at it from here [at the wrong angle], you see, it keeps going like this [sliding away from the anchor]. But at this [correct] angle, it does not move [away from the anchor] anymore.”

Master Chen concludes, “So that’s very, very important. You always have to find that solid connection, meaning a connection onto which it [the solid connection] doesn’t move anymore. And there’s a lot you have to do to get to that point. There are two ways.”

example 1. |

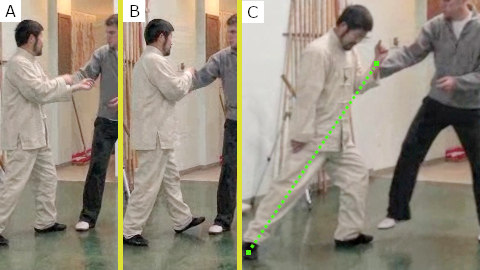

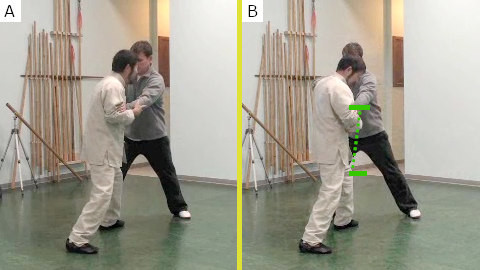

Master Chen proceeds to demonstrate how the ideas from the two models apply in the less ideal setting of push hands. He begins by telling his student, “Now you push me … just touch anywhere. You push. Can you see there’s no connection?” This initial position is shown in Figure 11A.

The student grabs Master Chen’s left arm and pushes on the forearm. Master Chen’s arm moves backward, showing that there is no connection between the student’s push and Master Chen’s structure. This action is illustrated in Figure 11B. |

Master Chen instructs his student to continue pushing. He responds with the proper reaction according to Taiji principles and explains further, “I use your push to show the suspended head. Where you touch is the head.” Master Chen makes an adjustment, and the student retreats from his position. This reaction is shown in Figure 11C, with the green dashed line indicating the resulting virtual connection between the hand and the rear foot.

Master Chen concludes, “You see? When I connect to the rear foot, the head is suspended. The inside is hollow.”

| Master Chen presents another scenario. He allows his student to grab and push on his elbow. This starting position is shown in Figure 12A. Master Chen explains, “I let you do the push, and I give you the connection. When it [the student’s push] connects to the floor, it’s suspended.” The result is illustrated in Figure 12B, with the green dashed line representing the connection between the student’s push and the rear foot. |

example 2. |

He elaborates, “This one [type of connection] is called solid. When I stretch it [to establish the connection], it [type of connection] is called empty.” Master Chen concludes, “Both actions [as described by the rubber band model or the stick model], either it’s solid or empty, whether it’s a push, your word, or a stretch, as long as it’s on the same line, finding that locked spot is called ‘suspended head’.”

Master Chen then expands on this important conclusion. “So that relationship is not only in the example of the suspended head, it should be throughout the body. In your own body and in connection with your opponents, at all times, you must have that.”

example 3. |

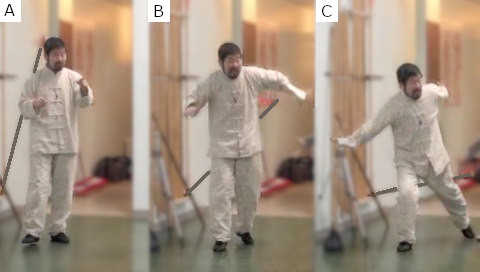

Master Chen then relaxes the rules of engagement. He encourages his student to grab him, and the student responds by holding Master Chen with both hands. This initial position is shown in Figure 13A.

Master Chen explains, “… When we touch like this here, I can use my finger [to establish the ‘suspended head’], can you feel [this connection]?” |

The student confirms that he feels the connection. His reaction is shown in Figure 13B, with the dashed green line indicating the connection.

Master Chen then summarizes the example: “It [my finger] connects to your foot, and it connects to my [rear] foot, it’s connected.”

| Master Chen offers another example. This time, he grabs his student with both hands. The initial position is shown in Figure 14A. He begins, “So I can also use this [the front kua].” The resulting outcome is illustrated in Figure 14B with the green dash line showing the established connection between the two end points. |

example 4. |

example 5. |

Master Chen continues, “See, when we are here, same configuration, I’m grabbing you the same way.” This initial position is shown in Figure 15A. Master Chen then switches the anchor point. He describes the change: “But I can use here [rear kua], can you feel that? It’s here [rear kua] connecting to you.”

He proceeds to demonstrate how the anchor point can shift to different locations. “I show you what I did. See, we’re here, right? So watch, I’m using here, but now I use here [front foot], can you feel it’s here? Now I use the front knee, can you feel the front knee is touching you?” This result is shown in Figure 15B. |

Master Chen concludes, “So through that training, that connection, alignment, can be reached in a spiral, in a straight line, in a straight vertical line, and in any action. Ultimately, when you are very familiar, very smooth with it, you can trace the energy and produce that connection that gives you the ability to fight. Because in fighting, the energy can be anything, can be, can come at any speed, any direction, any transformation. Because energy moves as you do, you have to have the ability to trace it. But to train, you have to find that first. And this is very, very difficult to train, or I can say it’s very, very easy to train. The difficulty is because of your fixed concepts. Or I can phrase it clearly, it’s because you’ve got the wrong concepts, you refuse to bend.”

| Returning to the beginning of the lecture, Master Chen states, “Let me give you an example. It’s because when you push me—yeah, yeah—everybody is told to be light, to do all sorts of things. Can you feel it’s totally useless? I can feel you moving around. It’s totally… I can’t find that spot.” This initial position is shown in Figure 16A. |

|

Master Chen then introduces the Practical Method approach. “So the spot is that… Ignore the Taiji concepts, the so-called, quotation mark, Tai Chi concept. Do this—lock everything into one piece. You push harder, you see, you already got it.” This tight and erect posture is shown in Figure 16B.

He then reminds his students, “But now the next part is, can you do that in action? Can you see the two procedures? Neither of the two procedures are what you heard before. The so-called loose, feel this, feel as if something is poking, feel it’s suspended—none of those will ever help you. So during the form, any part of the form, any part of your body is loose, you lose that connection. You lose it, yeah. So if it’s tight, you lose it too—but it’s connected, you don’t lose it. And that connection can be soft—you pull it. Can be hard—you squeeze it. So these are specific actions, methods to cause it to happen.”

concluding lecture. |

He continues, “Once you get it, you feel, yeah, it’s like I’m not using energy. But it doesn’t… you cannot get it by not using energy. Can you understand the procedure? That’s why it’s very, very important in Taiji that, according to Hong’s teachings, everything is reversed. Once you follow this rigid mechanical model, when you get it, you feel like, yeah, I am loose, I am very light. But by being light and loose, you’ll never get it. So the method is the opposite of what you achieve.”

Master Chen expands on this point: “When you truly achieve it, others will say, ‘Look, I’m pushing him, but he’s not using much effort. He’s not doing much. He looks completely relaxed.’ And yet, they can’t find it. They can’t find him. That’s because, in the moment of execution, he’s using physical, mechanical means to create the connection. Once it’s achieved, it functions just like that.” |

Master Chen emphasizes, “So that’s the suspended head. It has to be present throughout your entire body—in every direction, in every action—and it must be continuous. It’s there while you’re moving. Move a little bit. Yes, just push me, move a little. Can you feel it? It’s already there, in every direction. It’s always there.”

Master Chen finally concludes, “So whatever it is, can you see? I’m connecting through specific body parts. It’s not just about doing the movement—it has to be done this way.”

5. A Serendipitous Strike: Taiji in Real Time

In Taiji training, there is a well-known adage: “When practicing the form, imagine an opponent; when fighting, move as if practicing the form” (“练拳如对敌,打拳如练拳。”). While this principle is widely accepted in theory, it is often difficult to observe in real-life situations. However, there are documented instances where Taiji practitioners have demonstrated reflexive responses that align with their training, effectively serving as self-defense.

|

One such moment was serendipitously captured during the filming of this lecture. As Master Chen was speaking, a stick unexpectedly fell behind him—shown in Figure 18A—and struck his back, as seen in Figure 18B. Instinctively, Master Chen responded with the movement “Step Back to Mount the Tiger” (退步跨虎), the 78th posture in the Yilu sequence. This is shown in Figure 18C. |

to mount the tiger. |

This precise form is illustrated in Figure 19. Comparison of Figure 18C to Figure 19 offers a rare glimpse of a Taiji form and its application in spontaneous action. |

世上无难事,只怕有心人

|

Math seems easy—until you’re staring down homoisomorphism or wrestling with Fermat’s Last Theorem. Fighting feels simple—until the first time a punch lands in your kidneys and the world fades to black. Building a house is daunting, unless you’re an architect, for whom it’s just another Tuesday. Taiji is elusive, not because it’s inherently complex, but because its essence has been forgotten. As Master Hong once observed, everything is reversed. You cannot escape the Tao. |

|

In a pivotal moment from The Empire Strikes Back, deep in the misty swamps of Dagobah, Luke Skywalker struggles to lift his X-wing the from the bog with the power of the Force. Defeated, he tells Yoda, ‘You want the impossible.’ But Yoda, serene and unwavering, raises the ship with ease. Luke, stunned, gasps, ‘I don’t believe it.’ Yoda replies, ‘That is why you fail.’

Another lesson etched into the soul. Another thread in the tapestry of life. What seems impossible is often just misunderstood. What feels hard may simply require remembering what was lost—and believing that the impossible bends to those who refuse to give up. |

|