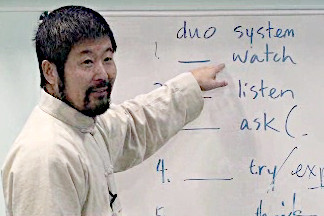

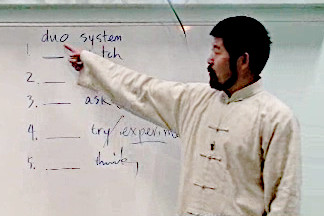

Master Chen Zhonghua, a student of Master Hong Junsheng (洪均生 1907-1996), summarized his teacher’s training system as the “Duo” system, derived from the Chinese character duō (多) meaning “more.” This system emphasizes a multifaceted approach to learning, prioritizing the following sequential steps:

|

|

By prioritizing the “Watch” step, learners can establish a strong foundation and optimize their learning experience, aligning with the wisdom imparted by Master Hong in his “Three Word Poem (陳式實用拳法太極拳三字經). [edited and transcribed based on Master Chen’s 2010 Edmonton seminar “How to Learn Taiji“]

A teacher that understands (求明師)

As Master Hong reminds us:

|

|

|

The journey of Taiji mastery is like scaling a vast and unyielding mountain, where each generation of practitioners follows the footsteps of their predecessors, seeking the elusive peak. Along this arduous ascent, the teacher serves as a guide—one who has traveled the terrain, faced its trials, and understands the obstacles that lie ahead. A true guide does not merely point toward the horizon but walks the path alongside their students, ensuring they do not falter or lose their way. Some, however, remain spectators—describing the view without ever making the climb. Others lead along well-worn trails but cannot explain why some stumble or why others struggle to advance. |

The greatest masters, those who have conquered the heights themselves, do more than instruct; they illuminate the way forward and provide the necessary support for each traveler to overcome their challenges.

Master Chen Fake (陳發科; 1887–1957) was one such guide, a pioneer who charted new paths while preserving the wisdom of those who came before him. Born in the humble Chen Village of Henan, he dedicated his life to the art of Chen-style Taiji. At 41, he moved to Beijing, where his exceptional skill and deep understanding of Taiji quickly established him as one of the greatest practitioners of his time. In his teachings, Chen Fake emphasized that Wu (武) is more challenging than Wen (文), as it requires physical ability and mastery of movement beyond intellectual understanding. His contributions became the foundation upon which future generations would build, providing a roadmap for others to follow.

Among his students, Master Hong Junsheng (洪均生; 1907–1996) was an unlikely climber—raised as a Confucian scholar, he lacked the traditional martial background that many practitioners possessed. Yet through rigorous training and immersion in Taiji, he climbed steadily, studying under Chen Fake for fifteen years. His persistence and unwavering dedication transformed him into one of the most outstanding Taiji masters of the modern era. Hong’s journey demonstrated that Taiji is not limited by one’s origins, but rather shaped by commitment and understanding. His teachings further refined Taiji principles, ensuring they remained accessible and practical for future generations.

Carrying this lineage forward, Master Chen Zhonghua (陈中华; 1961–) embarked on his own ascent. Initially specializing in linguistics, his background differed even further from traditional martial practitioners. Training under Hong Junsheng for seven years, he inherited the Practical Method, a precise and structured approach to Taiji. Despite the brevity of his direct training, he took upon himself the responsibility of guiding a new generation of Taiji students, sharing his knowledge with practitioners worldwide. His ability to bridge Eastern martial traditions with Western analytical methods allowed him to preserve and expand upon the teachings of his predecessors, ensuring Taiji’s continued evolution.

Despite their diverse backgrounds, Chen Fake, Hong Junsheng, and Chen Zhonghua all reached the heights of mastery by following a consistent learning system—a path refined through generations of practice and experience. Chen Fake understood that Taiji, like climbing a mountain, requires not only skill but a structured method that enables students to progress with clarity. His teachings provided a map for those who sought mastery, ensuring that the road to Taiji’s summit remained accessible for all who wished to undertake the journey.

In the end, the true measure of a master is not how high they have climbed, but how many students they have helped ascend. The legacy of these great teachers is not written in their own achievements alone, but in the strength, skill, and wisdom of those who follow in their footsteps, continuing the climb toward the heights of Taiji mastery.

Master Chen begins.

“This is the suggested learning method by Hong, known as the duō system. ‘Duō’ (多) means ‘more,’ and in this learning system, Hong said ‘You need to do more [多做] of these things — but in a sequential and prioritized manner.‘ The list is organized by priority, with the first item being the most important.”

1. Watch

|

|

“The most important thing is that you must engage in extensive watching, observing, and other visual-based activities. In the learning process, this means that, at the very beginning, your focus should be entirely tilted toward watching.

It means you must control your urge to act. When the teacher—especially when demonstrating the form—is showing you, you should refrain from trying it yourself. Stop all movement and simply watch. This is absolutely crucial. |

From an idealistic perspective, you should continue this process until your mind is fully saturated—until it is filled with vivid images of your teacher performing the movements. When the moment comes to act—to draw a circle or execute the first move [of the Yilu], Jingang Dao Dui” (金刚捣碓) will be attempting it physically for the first time. But by then, that move will have appeared before you visually, flashing in your mind’s eye countless times.

In other words, before you act, your mind should already be overflowing with the image of the movement. You are merely reproducing it with your body—the image is already embedded within you, fully absorbed, a hundred percent internalized. It is in you. You are not imitating; you are simply manifesting what has already been deeply ingrained.

[When it comes to learning], the challenge is that most people—and from my teaching experience, I know this—cannot be treated like children. We are dealing with adults, individuals with years of experience, many of whom have practiced for decades. In my case, most of the people who come to me actually have more experience with Taiji than I do. They arrive with their own agendas, driven by their desire to engage and act.

I want to do something [to demonstrate a Taiji principle], but as soon as I begin, they’ve already done it. When I demonstrate, they surround me, [already] trying to copy, moving in their own way. But that is the wrong approach to learning. You should never attempt something that isn’t fully understood or hasn’t already been internalized.

We don’t simply do—we absorb, saturating both body and mind until the movement is so deeply ingrained that it naturally wants to emerge. That is the procedure. But the method, first and foremost, [centers] on the image—the image itself. Watch it repeatedly until you can perceive its intricacies, until you can discern details that others might overlook. These [details] must be physical, tangible, and measurable.

Meaning, when you watch me perform [a single isolated movement of] the form, you see ten distinct things you can list [about that movement]. A beginner walks in. You ask the beginner, ‘Can you list [some details of] what you saw [in that movement]?’ The beginner responds, ‘Yeah,’ and [replies that he] sees only one thing. You ask again, seriously. And the beginner honestly says, ‘I only see this [one particular thing].’

Then you realize that your observation—the way you watch—allows you to see more things [than a beginner]. Only when you can see more things… can you act on them. You can never act on something you have not seen.

If we go back to that [learning] model, you begin to understand—you cannot do anything you have not seen.”

Master Chen use the example of teaching a secret move to highlight the importance of watching. Master Chen explains: “There’s a secret move—it’s called ABS. Now, if I ask you, can you do ABS? No. Why? Because you haven’t seen it. You’ve never heard of it. So how could you possibly do it?

But if you see it [the secret move], you believe you can reproduce it—because you have actually seen it. Now, imagine we take it further. When you see it [the move], I don’t allow you to execute it. … I [might] even restrain your body. [Sometimes,] I have my students hold their own hand [in front of their body as they watch me demonstrate]—because otherwise, as they observe, they instinctively attempt to mimic the movement.

Whenever you try to do this [mimic the movement immediately], you weaken the [vividness of the] image in your mind. Your brain shifts from observing to capturing [the movements in relation to your own execution], from watching to matching [your movements to my demonstrations]. As a result, you are not truly seeing much [in terms of details for that mental image]. In this way, [the result of] that type of learning [mimicking without a clearly established image] actually limits your ability to learn.

Everybody is endowed with the same ability [to watch and learn]. But unless you commit fully to it [by observing and capturing a mental image], you won’t truly see everything [the details of the movement], and when you attempt to practice, nothing will come out [because that movement was never fully internalized].”

Master Chen provides the following practical guidance to apply during this first phase of learning:

Look: Use your eyes to observe and commit the movement to memory.

- Observe – Stay still. Avoid moving your body or attempting to copy.

- Link – If you copy too soon, your brain associates what you see with your own incomplete

imitation, creating a false sense of understanding. This is how bad habits develop.

- Focus – Concentrate solely on seeing the movement clearly. Watch it repeatedly if needed.

- Adjust – Shift your perspective by changing your angle or point of observation for deeper insight.

- Resist – Avoid analyzing or judging the quality of the movement. At this stage, whether it is right or wrong does not matter.

2. Listen

|

|

“[Observation and listening are two sides of the same process—each shaping how we absorb and understand the world. First, you watch; then, you listen.] Watching is visual because, most of the time, we rely on images. Naturally, you hear far less, simply because fewer things in the world communicate directly with you. But everything is visual. When you open your eyes, countless images enter your mind. Yet, not everything speaks to you.

There is value in listening, as some things can be explained but not demonstrated. |

There are theories—concepts I can describe with precision but cannot physically replicate with the same accuracy. In this way, explanation compensates for what cannot be visually confirmed.

Although you may want to watch more, when taking notes, remember that what you hear is very likely more important than what you see. This is because while I can tell you what to do, that does not mean I can execute that action [with] 100% accuracy. [For example,] when I say [in a particular movement] that the center does not move, writing that down is crucial, as that [detail concerning the center is] very important. If you heard me [describing the action] but then watched me [performing the action], you might notice that I had slightly moved. Physical execution is always more difficult than simply describing a movement, because verbal instruction allows for certainty in stating, “this is how [the move should be executed].

The job of listening means that when you are hearing [the lecture], you should write it down. When you do, do not change any words. If I say ‘rotate,’ don’t write ‘turn.’ If I say ‘like this,’ don’t write ‘to the east’—even if I happened to be facing east at that moment. If I use the phrase ‘like this,’ you should write down ‘like this,’ because in the end, it’s better to not understand [the lecture] at all than to misunderstand it.”

Master Chen provides the following practical guidance to apply during this second phase of learning:

Listen: Use your ears to absorb and retain information.

- Hear – Focus solely on whether the words are clear. If anything is unclear, ask the teacher to repeat it.

- Accept – Avoid judging what you hear. Whether or not you agree with the teacher is irrelevant at this stage.

- Separate – Do not attempt to listen and perform simultaneously; give your full attention to listening first.

- Note – If new words or concepts arise, simply make a mental note rather than trying to process them immediately.

3. Ask

|

“The learning process: Step 3—Ask—should only be used after you have fulfilled the requirements of Step 1—Watch—and Step 2—Listen. You will have questions, but they should never come before you have done a significant amount of watching and listening. [This is because, after thoroughly observing and listening, your questions will stem from the teacher’s explanations and demonstrations, as well as the specific aspects of their instruction that remain unclear to you.] If you ask questions too early, they will be your own questions—questions that contain extraneous information, meaning information that was not obtained by watching or listening to the teacher. |

Taoists describe this state of learning as ‘having a question, but you should always try to make sure that you don’t have a question.’ Do you understand the difference?

The distinction lies in the approach: in one case, you are watching the teacher perform an action, setting aside [your own expertise or prior experience], and genuinely asking about what the teacher is doing. In contrast, students often ask questions that are not based on their observations or the teacher’s lectures.

For example, if the teacher demonstrates a movement and someone asks, ‘Oh yeah, Master Chen, in some other Tai Chi style, we do this—what do you think of that?’—that kind of question does not contribute to proper learning. However, a more constructive question would be, ‘When you perform this action, I cannot see your back. What is your back doing?’

In proper learning, ‘you have a question‘ because you are inquiring about the teacher’s movements or lessons. Yet at the same time, we can also say, ‘that’s not a question,’ because an inquiry is simply part of the learning process—it serves as a clarification rather than an external distraction.

The phrase ‘not a question‘ can also carry a negative connotation when inquiries introduce extraneous information that is not directly obtained by watching or listening to the teacher. Such information does not belong in this learning process; it is the student projecting something onto their learning. You should strive to keep external influences out of the lesson

In this learning process, questions can arise during a lesson when there is something you don’t understand. This means there is something you did not see or hear while the teacher was demonstrating or lecturing.

For example, a good question might be if you have seen the teacher perform an action countless times but suddenly notice a new detail and ask about it. This is considered a good question because it is directly relevant and does not distract the teacher from the subject material.

Therefore, refrain from asking questions that require knowledge outside the scope of the lesson. For instance, asking how the teacher’s performance compares to other styles of teaching is not productive. This is a bad question because it does not arise from watching or listening to the teacher but instead relies on the student’s prior knowledge.”

Watching and listening are solitary and passive activities, but they are crucial for beginning Taiji learning with the right perspective. The step of Ask allows the student to coordinate, analyze, and synthesize their lesson. ”

Master Chen provides the following practical guidance to apply during this third phase of learning:

Ask: Seek clarification without over complicating the learning process.

- Repeat – If something isn’t clear, request your teacher to repeat it.

- Simplify – Avoid asking “why” at this stage. The answers are often too complex and may slow your progress.

4. Practice / Experiment / Try

|

|

|

“The next step in learning is to apply what you have learned, a process that [Master] Hong referred to as ‘Try’ or experiment. When you experiment, you naturally generate more questions, but all of these questions stem from [the process of watching, listening, and asking]. This is the learning structure we are following here, as outlined in [Master Hong’s Duo system].” |

Master Chen provides the following practical guidance to apply during this fourth phase of learning:

Practice: Refine your movement by replicating what you’ve seen and heard.

- Trust – Your ability to see and listen is a natural gift. It is not inferior to anyone else’s, so do not doubt yourself in these areas.

- Adapt – Your ability to copy depends on life experience, and everyone’s ability varies.

- Accept – If your form differs from your teacher’s, don’t make excuses—listen, observe, and adjust.

- Validate – Others can see discrepancies in your form, and their feedback is valuable. Observation requires no special skill.

- Test – Ensure accuracy in your practice. Record your movements, use a mirror, and seek external feedback.

- Disregard Feelings – Do not rely on how the movement feels. Feelings can be misleading—focus on objective observation instead.

Experiment: Use push hands to assess the accuracy of your movements.

- Feel – Focus on whether your actions align with correct technique.

- Separate – Do not treat this process as a competition; it is not about winning or losing.

- Verify – The goal is to determine whether you can maintain your movements in push hands, just as you do in solo training. Physically you must quickly achieve one thing that will lead to future learning.

- Recognize – For most practitioners, actions in push hands often differ from their form, regardless of training volume.

- Refine – True skill lies in how effectively you train and apply your learning.

5. Thinking

|

|

|

“In the end, [the last step of this learning system] I say [is] thinking. [Master] Hong said, ‘In the end, you have to contemplate. You have to think about how all of these work together.’ This is the point where everyone believes they have created something—where everything comes together and begins to work. In reality, you are still engaged in [going through the sequential steps of watching-listening-asking-trying], but because of this process [of contemplation], there will come a time when you feel like you did it [created something]. However, if we follow the [sequential learning] process, when you [finally] think you did it [accomplished a goal], in reality, no—it is the principles that guided you [towards this goal].” |

Master Chen provides the following practical guidance to apply during this fifth phase of learning:

Synthesise: Mastery requires time; typically, it takes around 10 years to fully synthesise everything you’ve learned.

- Foundation – Mastery requires time; typically, it takes around 10 years to fully synthesise everything you’ve learned.

- Patience – Attempting to synthesise too soon will hinder progress rather than accelerate it.

- Integration – This stage is the culmination of all previous learning, bringing together the skills you’ve developed.

- Progression – Without successfully completing the first five stages, this final step remains out of reach. Learning and progress must be measured using concrete criteria grounded in Taiji principles.

6. The Importance of Preserving the Learning Sequence

|

|

|

“This [series of steps] is the learning method according to [Master] Hong’s instructions, or I can say it is the learning sequence. It appears very simple and does not align with widely accepted Western logic, but it is essential for learning this type of traditional skill. Why? Because you can see here [according to the sequence] that we cannot stop doing this [step 5 – thinking] at this stage [step 1 – watching]. As soon as you do this [thinking while watching], you disrupt the [defined] sequence [of this learning system].” |

“The value of the sequence lies in its structured progression—[a defined sequence] of steps: one, two, three, four, five. At step one, do not do six [Don’t think while watching]. At step two, do not do five [Don’t listen and experiment]. At step three, do not do seven [Do not mix the order of the sequences or combine them]. It is essential that this procedure be followed [exactly]. [Each time you gain new insight, you return to the beginning, reinforcing your foundation and refining your understanding. Mastery is built through continual repetition, allowing deeper layers of comprehension to emerge over time. Skipping steps or altering the sequence will disrupt your learning and eventually halt your progress.]

| You may think this is not difficult, but in reality, it is impossible. It seems simple, yet it is impossible. It is impossible for an intelligent, logical, educated Western adult to watch without wanting to act—to think, to add something, to believe, to rationalize. However, the true value lies in the ability to genuinely observe [at the very beginning and then proceed step by step]. If you do that, you will understand. None of those other things [you normally want to do] will get you started.” |

|

愚公移山

|

“Generation after generation will carry on the effort, The mountains won’t grow—so why wouldn’t we eventually remove them?” “子子孙孙无穷匮也, |

|

| Tang Wen (汤问); Liezi (列子) |

For 19 generations, practitioners of Chen-style Taijiquan have ascended the Taiji mountain, striving to reach its peak. Legends speak of its grand vistas, inspiring many to embark on this arduous journey. In the past, the path was treacherous—guides were scarce, knowledge passed down slowly in remote rural China, where teachings were transmitted personally, not widely spread.

As society evolved, communication became easier, and with it, Taiji’s fame grew. More people set out on the journey, more information became available, and yet fewer reached the summit. Observing with stoic amusement, the Taoists note this paradox: despite greater accessibility, true mastery remains elusive. When asked why, they sigh knowingly and remind us:

| “In the pursuit of knowledge, every day something is added. | (为学日益, | ||

| In the practice of the Tao, every day something is dropped. | 为道日损。 | ||

| Less and less do you need to force things, until finally you arrive at non-action. |

损之又损 | ||

| When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.” | 以至于无为。) |

This dilemma has only deepened with advancing technology. There is no shortage of information on Taiji, no hidden mysteries left unexplored, yet the peak remains an illusion.

Master Hong, understanding the Confucian wisdom “Desiring speed leads to failure” (欲速则不达), offers a methodical, step-by-step approach to scaling the mountain—no shortcuts, no flashy detours, just steady, deliberate ascent.

Master Chen complements Hong’s traditional method with modern technology. Now, learners can watch and listen to authentic instruction anytime, anywhere. They can ask questions directly, engage in hands-on practice, and refine their skills through workshops and recommended schools worldwide. To succeed in the Practical Method of Taiji learning, one must adhere to the following steps:

|

|

Can you truly reflect on what you’ve learned, resist the temptation of easier paths, and keep climbing?

How many generations will endure this arduous ascent, refusing to turn back? And how many will settle for the comfort of smaller hills, abandoning the pursuit of the true summit? Will they be content with partial success, knowing that a grander, more breathtaking view lies just beyond the next climb? The peak remains—not unreachable, but reserved for those who never stop ascending.