|

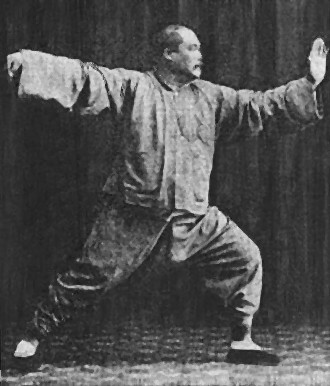

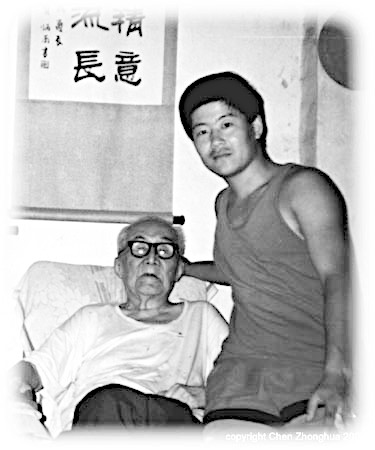

The following edited transcript is drawn from a Q&A session at an Open House in Ottawa in 2014. In this discussion, Master Chen explores a range of thought-provoking topics, including the distinctions between Tai Chi styles, selecting the right teacher, the intricacies of the “God Syndrome,” the nature of fame, and the life of his teacher, Master Hong Jungshen—a true Taoist. You can find the full Q&A video here, the video for the Ottawa Open House 2014 (for members only), an edited transcript entitled “Star Map for Taijiquan“, along with my review of the event. |

Master Chen once observed that most people ask questions expecting answers that align with their existing beliefs. As a result, it is easy to cater to an audience by recounting Taiji’s greatest hits, earning admiration without challenging perceptions. However, Master Chen takes the more demanding path, presenting insights that require thoughtful reflection and deeper engagement to grasp the subtle arguments at play.

|

|

1. Mystery of Accuracy, Style, and Personal Preference

Q: Why is Taiji so mysterious?

The mystery is again, accuracy.

Q: So in terms of improving health, what would you suggest to practice Yang style or Chen style, which one would be suitable for you.

A style can emerge for one of two reasons. The first is simple: it’s a mistake—you didn’t execute it correctly. Consider this analogy: Suppose I’m learning French. One day, I meet a French speaker and try to converse in French. He looks at me, puzzled, and asks, ‘Master Chen, what did you just say?’ I respond, ‘I spoke French.’ But he shakes his head and says, ‘No, that’s not French. I have no idea what you’re saying.’

|

Now, instead of admitting I’ve been speaking French incorrectly, I could rename my speech ‘Chenlish.’ Since you’ve never heard of it, I could insist it’s a special language I just created. If you don’t understand me, I could shift the blame onto you—claiming that you lack knowledge, that it’s your fault for not knowing Chenlish. But the truth is, nobody else speaks this language, and that’s the real problem.And that’s the first reason a new style might emerge—you didn’t do it right. |

The second reason is quite different: you did it right, but the name for the action changed due to historical or emotional significance. Suppose, during your study, your teacher passes away, or perhaps he performed a heroic act—saving someone’s life, for instance. You feel deeply moved and decide to rename the style in his honor. That would be understandable.

Another possibility is that your teacher profoundly shaped your life. Maybe you were abandoned, and he took you in, rescued you from danger, or even pulled you from the jaws of a tiger. You want to honor his impact on your life, so you name the style after him.

But beyond these two reasons, Tai Chi remains Tai Chi.

So, what is Tai Chi? Move in a rotation. And what is a rotation? A full 360 degrees.

That’s why, when this question was asked to my teacher, Master Hong, he said, ‘How many methods are there to complete 360 degrees? Is your circle 361 degrees?’ So, if you’re a brilliant scientist and you decide my circle has only three degrees—what kind of circle is that? Well, you know, maybe I’m ignorant or something. Maybe I’m from another planet, because I’ve never seen a circle with only three degrees—usually, it’s 360. And once you understand the true nature of 360 degrees, there can be no variation.

Style, on the other hand, is all about personal preference. You can’t change the fundamental reality of a circle, but you can choose how to approach it. Imagine trying to draw a perfect circle but deciding an egg is ‘close enough’—that’s a matter of style, not precision. The egg isn’t truly a circle, but if someone insists on seeing it that way, they’ve made a choice based on their own perspective rather than mathematical accuracy.

That’s how we live—accepting things as they are, even if they aren’t truly what they claim to be. We adapt. We make do. Because in life, we are what we are—we can’t be too idealistic. You want to be a communist? It might sound appealing, but reality isn’t always that simple.

Q: Should I choose Yang Style or Chen Style?

| I might say, ‘Abandon your Yang style and learn mine,’ but only because I practice Chen style. That statement holds just as much weight as saying, ‘Stick with your Yang style.’ In the end, it’s all the same—it’s simply a matter of personal preference.The key is to practice with the right alignment and energy movement—without deviating from the original motion that created the universe. If you’re unsure how, consult a scientist or just Google it. The answers are all there. |

|

2. Finding the Right Teacher and Style Through Experience and Fate

Q: Tai Chi is Tai Chi, but with different styles. When someone opens a school and teaches Tai Chi, how do you distinguish between the various approaches? How can you recognize the differences between styles?

There is no difference in Tai Chi, there are differences in the teacher.

Q: How how do you choose the right Tai Chi to follow?

Assume you are—let’s say—experienced. Meaning, in terms of age, someone like me. So, this advice? Not for the young.

For them, I’d say: follow your love. Seriously. If you love it, if you want to do it, if you wake up in the morning feeling like you need some Tai Chi—go for it.

And if you not only think, “I need some Tai Chi,” but also, “I think I need Master Chen,” then buy one of my DVDs. Put it on.

You know, wake up in the morning, pop in the DVD—into your computer or something like that.

That’s specific advice for the young.

|

Well, for the rest of us, I don’t have the “right” answer or the “perfect” solution. But let me share my experience with you—because, in the end, nothing else will truly help. Finding the right teacher? That’s pure fate.The truth is, I was fortunate enough to find my two masters—two of the greatest in modern Taiji history. People often say, “Master Chen, you must have had a method, a plan that led you to them. You didn’t waste your time.” But the reality? I never studied with anyone else. I went straight to my teacher, Master Hong. |

So when people ask me for advice, my answer is simple: he was the only person in my neighborhood. And as for those outside that neighborhood? They wrote books on how to find a teacher—but never found one for themselves.

3. Nature of Knowledge: Recognition, Fate, and the Paradox of Learning

Q: The reason I asked this is that I am old and I cannot let my fate carry me. I’m coming to the end of my life …

I’ve given you the definitive answer: there’s nothing you can do. But together, we can take action—like a reversed pyramid descending step by step. In learning, we often start with a broad foundation of general knowledge, gradually narrowing our focus to specialized expertise. Similarly, our approach here starts with big ideas and systematically refines them into precise action.

At the beginning of your search, the possibilities stretch endlessly before you—it’s wide open. Yet, paradoxically, there is no single destination, because the journey itself is the pursuit of knowledge. As university students, you embody this quest—the relentless search for truth, understanding, and the deeper wisdom that shapes our universe. Let’s embrace that idealism.

But what is knowledge, really? How do we grasp it? To attain it, we need a method. Yet how can we define a method when we don’t even fully understand what knowledge itself is?

With age, we may accumulate insights—we might know a little more than the young. But when measured against the vast unknown, we are still grasping in the dark. How, then, can we construct a method to explore something that remains undefined?

Imagine someone standing before you, challenging you to come up with a question. They’ve given you ten pieces of information—but you can’t hear them. Now, you’re told to proceed. But from where? How do you begin when the very foundation is obscured?

This is the nature of knowledge — elusive, demanding, always just out of reach, yet urging us forward.

To tackle this problem, let’s take a step back and ask: How does knowledge come to us?

| Think about your brain. Have you ever imagined it opening up, allowing you to peer inside? Of course, I’m not suggesting you do this literally. But I have a method—a way to observe my own mind every day. It’s called the Practical Method. With it, I don’t need to physically open my brain, yet I can still see what’s happening within.This method involves documenting my daily activities. I have kept a journal since junior high, continuing the practice to this day. |

|

At least once a year—often more frequently—I reflect on my past experiences, sometimes looking back as far as 20 years. In revisiting my old journals, I’ve noticed something peculiar, something I have yet to fully explain. I would read a page and highlight certain paragraphs, seemingly at random. Yet, decades later, I realize those passages always carried meaning—they reflected my interests, my inclinations, the very ideas I was drawn to without consciously knowing why.

This paradox lingers—learning is meant to unveil the unknown, to illuminate fresh insights hidden within the pages of a book. Yet, as I look back, the words I once highlighted were not revelations but reflections of an instinctive pull, echoes of thoughts that had already resonated within me.

I highlighted this paragraph—but how did I know I liked it? I must have known, instinctively. Now, let me go back another twenty years—when did I first recognize this affinity? It’s similar to how we sometimes feel an inexplicable connection to someone simply because they remind us of someone else—a student I once had, for example. But where did that original feeling begin? How did I come to like that student in the first place? Where does it begin? How does knowledge, recognition, or preference take root?

And therein lies the contradiction—the recursive nature of knowing, of being drawn to something before fully understanding why. That contradiction, perhaps, is what we call the God Syndrome.

The God Syndrome suggests that when you were created, everything was already within you—every experience, past, present, and future, embedded in your mind. When you encounter someone and feel an immediate connection, it is not mere coincidence. Your brain, searching its vast archive of impressions, identifies something familiar, triggering that sudden recognition.

If a person or concept were never within your mind, how could it enter? From this perspective, learning—especially through reading—is not about acquiring entirely new knowledge but rather recognizing and reconnecting with what was already there.

In essence, we are born with everything, yet remain unaware of it. The Taoist philosophy addresses this paradox through the theory of Yin-Yang separation: all things exist in duality. Nothing stands alone—you cannot talk to yourself, nor can knowledge surface without an external trigger. The internal reveals itself only when stimulated by the external.

The information is always there. I see five people walk by, yet I only speak to one. Why? The other four were never placed in my mind—God did not weave them into my consciousness. Every day, I pass countless strangers on the street, but I never engage with them. There is no past-life connection binding us, no thread of familiarity. Many religions explore this theme of recurrence—the idea that the people we are drawn to have appeared in our lives before, echoing across time.

If those information wasn’t there, how would you know?

For example, I’ll give you a brief glimpse into this topic, but the real purpose is to introduce this DVD. This is one of the best videos I’ve created on the Basic Foundations, filmed on location at King’s Park in Perth, Australia. It covers all the foundational exercises with exceptionally clear explanations. The cinematography, beautifully captured by professional videographer Paul Jansons, enhances the experience. By purchasing this DVD, you’ll gain a deeper understanding of the foundations.

Back to my point—if a DVD is blank, no matter how many times you play it, no images will appear. Something must be recorded for it to be played. Similarly, the brain must already contain something—an imprint, a memory, a framework—to recognize and process knowledge. Without pressing play, the DVD remains empty, its potential unrealized. Likewise, without an external trigger, learning stays dormant. But once activated, whether by a machine or a stimulus,recognition emerges.

4. Tai Chi, Taoism, and the Illusion of Fame

Q: The moment you say, ‘I’m going to learn Tai Chi,’ fate is already in motion. The decision arises suddenly—but how do you know it’s the right path? How do you know your teacher is the right guide for you?

Returning to the answer from your previous question—if you’re young, explore freely. Train with your teacher, observe, and decide over time whether their approach resonates with you. You may come across reports questioning their credibility, but discerning the truth takes time. As you grow older, time feels more precious, and you may no longer have the luxury of trial and error. When that happens, there is a method—a structured way to find the right path. That is what I am showing you.

The key is learning to go against your instinct—that’s exactly how Tai Chi fighting works. Your instinct says, ‘I should punch him.’ Don’t.

We often equate fame with ability, but that assumption can be misleading. Take, for example, a world-renowned movie star. Beneath the glitz and glamour—the $5 million wardrobe, the designer dress, the layers of makeup—lies a reality far removed from the illusion. When the lights dim and the façade fades, you might not envy the person behind it all. Fame, after all, is often just smoke and mirrors. And that celebrated star? They are not your Tai Chi teacher.

I once asked my teacher, Master Hong, a similar question. He gave me an answer that I hope will resonate with you. Master Hong said, ‘Remember, the rules are simple—you do not deviate. Do not think this is special. Everything follows the same principles, and nothing exists outside the control of gravity. Therefore, there are no exceptions to the rule.’ The rule my teacher shared with me was clear: ‘As long as a person is alive, that person should not be famous.’

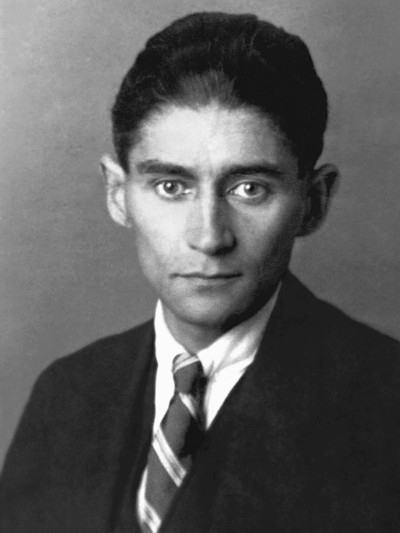

| In traditional Chinese belief, fame is not something given lightly—it must be earned over time and comes at a significant personal cost. The greater the fame, the higher the price. It’s like the fate of a true artist who, in their lifetime, goes unrecognized and starves to death. A century later, people finally see the brilliance of their work and wonder, ‘Why did no one appreciate this back then?’ As time passes, the value of the art skyrockets—now worth $50 million—but the artist never lived to see their success. Artists like Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890) and Franz Kafka (1883–1924). Van Gogh battled severe mental illness, enduring self-harm and a tragic suicide, yet his groundbreaking art gained posthumous recognition, shaping modern painting and cementing his legacy as one of history’s greatest artists. Kafka endured anxiety, illness, and deep alienation, leading to his early death at 40. Though overlooked in his lifetime, his works gained lasting legacy of praise, profoundly shaping modern literature. |

|

From my own experience, my Master, Hong Jungshen—now revered as one of the greatest Taiji masters in the modern era—died of starvation, abandoned by the very world that would later honor his name. Twice, hunger left him paralyzed. I remember vividly: when we visited his home, he was on the street, scavenging for food, eating what others had discarded. In ninety years, not once did he complain. He was eating garbage and the sight of him doing so could bring tears to your eyes. Seeing our distress, he consoled us, saying, ‘You know, everything that goes in here will get fermented. It’s the same thing. Yours will get fermented there, mine got fermented here. See, I got less work to do.’

Sŏng’u (성우; 1849–1912) |

That was the life of a true master—one of unwavering dedication. Times have changed, and we can’t live that way anymore. I do charge for my workshops, so if you haven’t paid yet, please check with the organizers. But all jokes aside, my teacher devoted ninety years to teaching without ever asking for a single dollar. In that way, I am not as good as him. I can’t claim to be, because I can’t silence my own desires without charging for what I do. Master Hong could go six, even seven days without eating. Imagine the worry and helplessness we felt as his students, finding him time and again locked in a locked in a standoff with a chicken — both eyeing the same meager scraps of food.Master Hong’s hardships and struggles never shook his perspective on life. Even in his final moments, his resolve remained unbroken. His last words to his disciple were, ‘Go talk to the doctor. Is there another way to make me last one more minute?’ |

Why? It wasn’t a selfish request. He understood that life is simply life—nothing more, nothing less. There is no good, no bad. Life is life. Another breath is life. Another breath is simply another breath. It doesn’t mean this is a life of comfort, nor does it mean it is a life of suffering.

A true Taoist does not dwell on such distinctions, for they are constructs of the mind. When we say that eating bread is better than eating chicken feed, that judgment exists only within us. It is our own perception, our own division. The universe does not make such choices. On this earth, in this vast existence, no such decision was ever made—only we have assigned meaning where there was none.

In ancient times, people ate differently—less meat, and certainly no instant noodles. Yet, they likely lived rich and fulfilling lives. They shared jokes, gathered in celebration, and enjoyed each other’s company. They laughed, they drank, they loved, they fought, and they felt the full spectrum of human emotion. No matter how far back you go in history, life was never just about survival—it was lived in all its depth and vibrancy.

The modern audience might pity ancient societies for never having iPhones. Right? Yet, as technology continues to advance, today’s iPhones will one day seem primitive. Future generations will look back at us, just as we look back at those before us, and say, “The people of 2014 played with rudimentary gadgets like iPhones.”

They will see how the desire for an iPhone sparked arguments—how people longed for it, even when they couldn’t afford it. But why? Because, at that moment in time, it held meaning for them.

Is that what defines a good life?

A true Taoist believes that time is life—life equals time. Nothing more. Everything else is an illusion of the mind. In the vast universe, only one thing is undeniably real: time.

All else is shaped by perception. Becoming a man or a woman, growing tall or short, gaining wealth or living in poverty—these are constructs of the mind, fleeting and subjective. None of them alter the fundamental reality that time remains unchanged, unaffected by anyone’s beliefs or circumstances

The true pursuit of the Practical Method unfolds through seven distinct methods. The journey begins with the Foundations. As you progress through all seven, layer by layer, everything disappears—until, in the end, only time remains.

For the general public, time is often understood through clocks, calendars, and schedules. But in Taoist thought, time holds a deeper meaning. Taoists see time as a rhythm—a natural flow rather than just a measurement. At the highest level of the Chen-style Tai Chi Chuan practical method, practitioners work solely with rhythm, embodying this Taoist perspective. This is how Taoism connects to Tai Chi and to what we practice—it’s all about rhythm.

Returning to the original idea—going against your instincts is never easy. Why? Because why would I choose to learn Tai Chi from someone who isn’t famous when there are so many reputable teachers available? The answer is simple: every so-called reputable teacher is not real.

Here’s a personal story to illustrate my point. Many years ago, in 1991, my Tai Chi brother took me to see a famous master in China—who has since passed away. That experience changed me; I became enlightened. But my Tai Chi brother did not.

This is just my personal opinion, so the story might be biased. After all, I tend to favor myself when recalling the past—just like everyone else, right? We all like to think we’re better than we actually were.

| We went to see this master—historically the first millionaire in Chinese martial arts—living in a grand house. But what I saw convinced me that he did not truly know martial arts.The reason? He proudly revealed his cabinet—a towering, glass-covered display spanning an entire section of the room. Inside, shelves overflowed with certificates, honorary degrees, and titles like ‘Honorary President’ of various associations—nearly 2,000 in total.

In that moment, I realized—I didn’t want to be that person. Imagine if he spent just two days securing each certificate, traveling to ceremonies, receiving awards—his life would have been consumed by the pursuit of recognition rather than the mastery of Tai Chi. He wasn’t practicing; he was collecting accolades. |

— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. |

Yet, my Tai Chi brother admired him. “I want to be like him,” he said.”—wealthy, famous. Look at the people who come here just to worship him.”

I replied “But all we want is Tai Chi.”

Then I continued, “Look at all those honorary distinctions—how many there are, how they stack up, how they correspond to his age. His entire life—starting, let’s say, at 30—became a pursuit of accumulating them. There simply wasn’t enough time for this master to personally receive each award. Many arrived by mail—ceremonies he never attended, people he never met. Yet, he kept collecting them, one after another.” And in that moment, I knew—I don’t want to live like that.

My Tai Chi brother did not reply and remained silent.

Twenty years later, my Tai Chi brother lost to me. It was real—he had always been far superior, someone I could never defeat. Yet, after two decades, the outcome had changed. That was the moment I decided to quit.

Why? Because he had chosen the path of fame, while for me, Tai Chi was never about recognition—it was about daily practice. I preferred working with small groups, engaging directly with the people. When I was in Italy, I found myself among 65 students, and by the end of the day, I was exhausted. Our Practical Method is hands-on; I have to physically connect with everyone. If you haven’t worked with me before leaving, then you haven’t truly learned. Passing on knowledge requires direct experience.

But fame demands time and sacrifice. If you seek recognition, you cannot fully dedicate yourself to Tai Chi. And sometimes, that means going against your own instincts.

You know the famous figures—the ones who appear on TV shows with flashy graphics, dramatic music, and high production value. In contrast, my videos are entirely self-made, filmed by a student with me looking directly into the camera. Every video is focused solely on me teaching, practicing Tai Chi, and recording it. There’s nothing else—just pure, authentic instruction.”

That method won’t work—it’s simply too difficult to make that choice. Why would anyone seek out an unrecognized teacher over a famous one? The truth is, human nature is predictable. This scenario plays out time and again.

| On one side, there’s an authentic master—skilled, devoted, but largely unknown. On the other, there’s a famous figure, drawing crowds effortlessly. People flock to fame, and within a week, they’ve signed up with the well-known teacher. I’ve seen it happen too many times.Choosing the unrecognized teacher requires patience and hard work. Choosing the famous one offers instant gratification. A single photo with a renowned master is enough—suddenly, everyone knows your name. |

|

Deep down, every person wrestles with this tendency, and it’s something we cannot change. So while it may not be the best approach, it’s the reality we live with. And beyond that, there’s little left to say.

「今を生きる」 (Ima o ikiru)

|

The legendary poets Mick Jagger and Keith Richards once proclaimed in 1969, “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find you get what you need.” This wisdom applies beautifully to those attending Master Chen’s workshops.Approach each session with an open and unbiased perspective. Engage in hands-on practice as often as possible. Discuss and test your newfound understanding and abilities with peers. Remember to review and re-watch the workshop videos—you may be surprised by how often you gain fresh insights. |

In the West, the saying “Time is money” reflects a view that prioritizes efficiency and productivity. However, Master Chen reminds us of a deeper truth: “Time is life.” A well-known Chinese proverb captures this wisdom—”一寸光阴一寸金,寸金难买寸光阴” (“An inch of time is worth an inch of gold, but an inch of gold cannot buy an inch of time.”)—emphasizing the irreplaceable value of every passing moment. Time is not merely a resource to be spent; it is the essence of our lives, and how we choose to use it defines our journey.

Practice consistently. Persistence and adaptability often lead to unexpected yet essential discoveries.