|

The Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi (朱熹; 1130–1200) of the Southern Song dynasty eloquently stated, “Knowing is the beginning of action, and action is the completion of knowing” (知是行之始,行是知之成). This profound insight highlights the essential interplay between intellectual understanding and its practical application. Students, inspired by the opening line of the Analects—“Is it not pleasant to learn with a constant perseverance and application?” (學而時習之,不亦說乎?)—embark on a rigorous journey of study and introspection. Teachers, like the esteemed Tang Dynasty scholar Han Yu (韓愈; 768–824), fulfill their vital role in “transmitting the Way, imparting instruction, and resolving doubts” (傳道、授業、解惑), guiding students to deeper understanding.

|

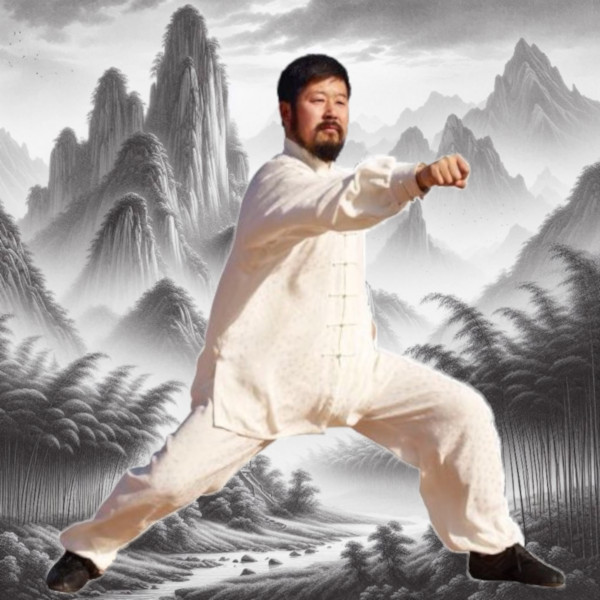

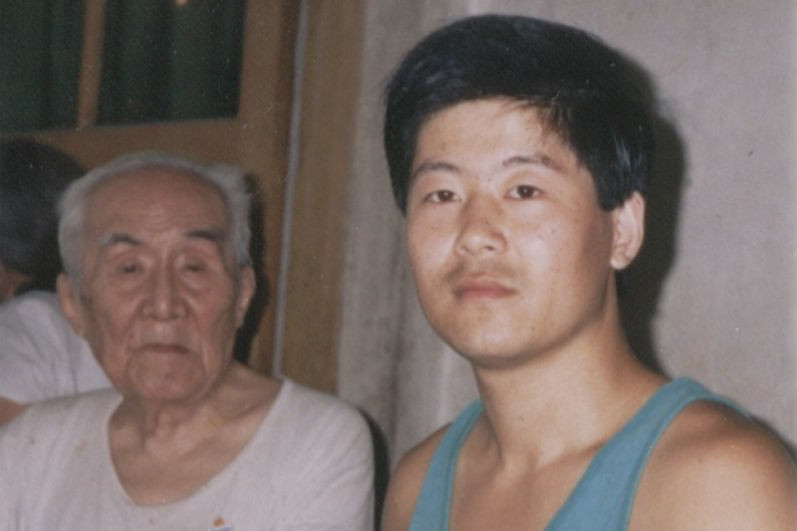

Yet true mastery transcends teaching, as sages and masters achieve harmony with the natural order through years of dedicated practice and profound understanding. Zhu Xi emphasized this principle with the phrase “Investigate things to know” (格物致知), underscoring the pursuit of understanding the underlying principles (理, li). Master Chen Zhonghua, inheriting the Chen-style Practical Method from his esteemed teachers, Master Hong Junsheng and Master Feng Zhiqiang—disciples of the legendary Chen Tai Chi Chuan Master Chen Fake—embodies this profound principle. With over forty years of experience as a student, teacher, and master, Master Chen exemplifies the unity of theory and practice, offering unique insights into the style and characteristics of the Practical Method.

|

Translated and adapted from

The style characteristics of Chen Zhonghua Tai Chi

(陈中华太极拳的风格特点) Published on April 17, 2021

|

1. Movement gives rise to Yin and Yang – Principles of boxing (动分阴阳-拳法原则)

2. Principles of Spiral Force Generation – Rules Governing the Application of Strength (螺旋缠丝-劲路规则)

3. The Center of Gravity in Tai Chi: The Importance of Overall Shape (重心在中-整体形状)

4. Retracting the Elbow to Release the Hand: Principles of Movement (收肘出手 – 动作原则)

5. Concave circle comes first – Action’s external shape (凹圈在先-动作外形)

1. Movement Gives Rise to Yin and Yang – Principles of Boxing (动分阴阳-拳法原则)

|

In Taoist philosophy, movement inherently divides into Yin and Yang, complementary forces that interact and balance one another. This principle, “Movement divides into Yin and Yang, stillness returns to the infinite” (动则分阴阳,静则归无极), is central to martial arts, particularly the Practical Method. The essence of this idea lies in ensuring a clear Yin-Yang separation within all movements. Unlike simple oscillation or imbalance, this principle embodies a harmonious interplay of opposing forces, extending its relevance beyond martial arts to all human motion. |

The Practical Method provides a systematic approach to internalizing this principle, starting with the concept of a ‘point’ in space. When two opposing actions of equal magnitude meet at a point, it becomes a ‘midpoint,’ serving as the axis for Yin-Yang dynamics. These opposing actions can manifest as displacements, energies, or forces, categorized by their direction and nature:

|

Each of these categories illustrates unique ways to achieve Yin-Yang separation, whether through vertical movements (upward and downward) or spiral and fluid silk-like motions.

| The importance of Yin-Yang separation in Tai Chi Chuan was first articulated by Wang Zongyue (山右王宗岳) in The Tai Chi Boxing Classic (太極拳經): “Taiji, born of Wuji, is the source of Yin and Yang” (太極生於無極,是陰陽之母). Master Hong Junsheng emphasized this principle further in his poem: “In Chen Style Taijiquan, the theory is profound, and the method intricate. The concept of Yin (陰) and Yang (陽) governs their interplay” (陳太極,理法精,陰陽理,互變中). Recognizing the separation of Yin and Yang within every movement is paramount in the Chen Style Practical Method. As Master Chen highlighted, this principle must be evident in every technique or sequence, making it an indispensable foundation of the art. (打上眼,一眼就能看出来特别重要). |  |

2. Principles of Spiral Force Generation: Rules Governing the Application of Strength (螺旋缠丝-劲路规则)

|

Spiral silk wrapping (螺旋缠丝) is a foundational principle in Tai Chi, combining classical theory with modern insights. While the term “spiral” (螺旋) originates from mechanical engineering, its essence aligns with the traditional concept of “silk wrapping” (缠丝), which describes the continuous, spiraling movement of energy and force throughout the body. |

This principle reflects the philosophical balance of Yin and Yang and is rooted in Wang Zongyue’s boxing theory (王宗岳的拳论), which states, “Movement divides, stillness unites” (动之则分,静之则合). In Tai Chi, this division arises from turning motions, which separate Yin and Yang. This turning represents an auto-rotation (自转) around a central axis. Though seemingly stationary, when combined with linear displacement, it forms a spiral (螺旋), which serves as the basis for generating and utilizing internal force in Tai Chi.

| Master Hong Junsheng emphasized this principle through his concept of “revolution plus rotation” (公转加自转), which explains the interplay between linear and rotational forces. Revolution (公转) represents a turning motion around a fixed axis, like a spinning top that rotates but remains stationary. By adding rotation (自转), which introduces linear displacement, the two motions combine to create a spiral, analogous to the threads of a screw or the forward motion of a drill bit. This spiral generates immense force and dynamic energy. |  |

In Tai Chi, this principle manifests as spiral silk wrapping, where the body generates continuous spiraling movements to cultivate internal power and apply force effectively. Master Hong viewed this concept as fundamental to Chen Style Tai Chi Practical Boxing Techniques, emphasizing that “The myriad of changes are rooted in one source; only silk reeling is the foundation” (法萬變,不離宗,唯纏法,基本功).

|

This principle extends beyond Tai Chi, evident in martial arts, dance, and nature. For instance, a circular saw blade rotates while stationary, but when pushed forward, its rotational and linear motions combine to cut through wood. Similarly, Tai Chi practitioners must integrate spiral silk wrapping into every movement. As Master Chen stressed, “When practicing boxing, we must always wrap the silk in a spiral” (所以练拳的时候我们要求时时刻刻,都要做到螺旋缠丝). |

3. The Center of Gravity in Tai Chi: The Importance of Overall Shape (重心在中-整体形状)

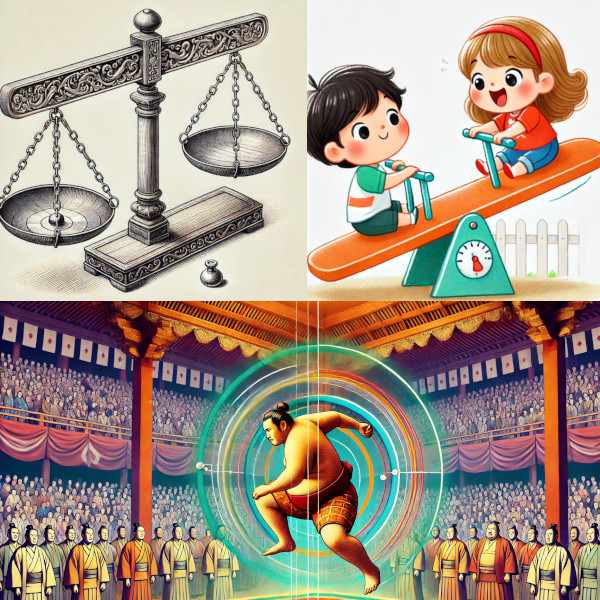

| In Tai Chi’s Practical Method, the center of gravity (CG) is paramount. In physics, the CG is the point where an object’s mass is considered concentrated, and for the human body, this point shifts dynamically with every movement. Understanding this shifting CG is crucial for grasping Tai Chi’s principles. A helpful analogy is the seesaw, where the CG is represented by the fulcrum. The turning effect of force is governed by the principle of moments: to maintain balance, clockwise moments must equal counter-clockwise moments. |  |

|

The Practical Method emphasizes the manipulation of the CG through precise hand placements, stances, and specialized techniques, such as “waist-crotch conversion” (腰裆转换). This subtle shifting of the CG allows practitioners to create instability in their opponent without relying on brute force. Unlike traditional martial arts, which often depend on strength, Tai Chi relies on the principle of “Four ounces overcoming one thousand pounds” (四兩撥千斤), where practitioners use leverage to redirect an opponent’s force, achieving control with minimal effort. |

This approach transforms the human body into a dynamic system, leveraging the principles of physics for maximum efficiency. Like a lever system, Tai Chi practitioners use their body as a lever, with the CG acting as the fulcrum. When the CG is balanced centrally, force distribution becomes efficient, resulting in fluid and powerful movements. Mastery involves fine-tuning this balance through subtle shifts in weight and body position, allowing the practitioner to neutralize the opponent’s strength.

| By integrating revolution, rotation, and spiral silk wrapping with leverage principles, we see that the fundamental shape of Tai Chi movements is circular. A wheel and axle exemplify this: the axle is the fulcrum, and the wheel is the lever arm, amplifying force with minimal effort. Master Hong Junsheng captured this concept beautifully: “The theory of leverage resides in the pivotal point, Like a balance scale measuring grain, When weight is added, The counterweight shifts accordingly, Ensuring the center of gravity remains balanced.” (支重力;如磅秤,稱糧米,物加重,砣隨移,使重心,得隨遇,守中立,莫挪移). |  |

In summary, the Practical Method of Tai Chi focuses on mastering the manipulation of the CG and leveraging mechanical principles like the fulcrum, providing practitioners with the tools to move with speed, power, and grace while maintaining balance and control over the opponent.

4. Retracting the Elbow to Release the Hand: Principles of Movement (收肘出手 – 动作原则)

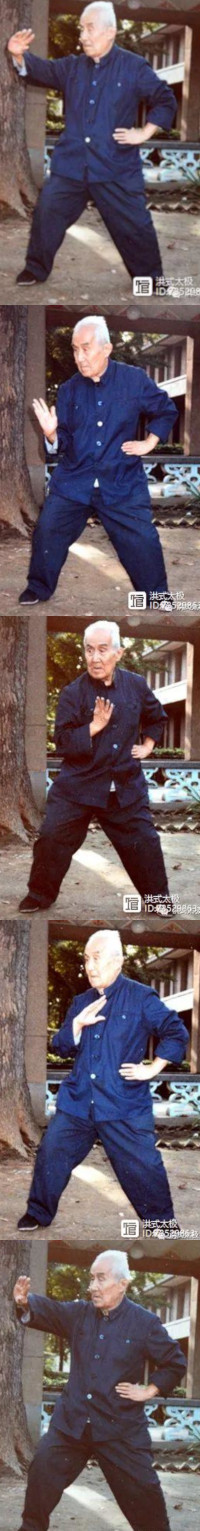

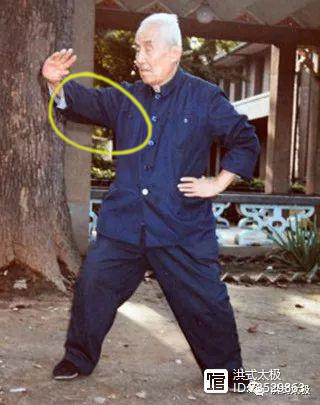

| Master Hong Junsheng made significant contributions to Tai Chi Chuan, particularly by observing that all Tai Chi movements involve circular hand and arm motions. He categorized these motions into positive circles (正圈), where the elbow retracts below the chest and concludes with an upward hand release, and negative circles (反圈), where the elbow retracts above the chest and ends with a downward hand release. This focus on the interplay between the elbow and hand is encapsulated in his “Ten Word Mantra” (十字真言), also known as the “Ten Word Formula” (十字诀): “收肘不收手;出手不出肘” (“To retract the elbow but not the hand; to extend the hand but not the elbow”). For beginners, this complex concept is simplified as: “肘入,手出” (“In with the elbow, out with the hand”).

Master Hong, a student of Master Chen FaKe, described Chen-style Tai Chi as “the art of peng energy” (掤劲), emphasizing that “太极是掤劲,动作走螺旋” (“Tai Chi is about Peng energy; movement follows spirals”). He likened peng energy to the inflation and deflation of a balloon: expanding air from within inflates the balloon (internal energy expanding outward), while external pressure compresses it (external energy moving inward). This dynamic mirrors Tai Chi’s principle of Yin and Yang, where movements originate from the core (inside), expand outward (outside) during extension, and return inward during retraction. Peng energy maintains the balance between expansion and contraction in Tai Chi postures, ensuring structural integrity. This principle underscores the importance of preventing the opponent from compromising the body’s structural integrity, whether in push or pull movements. The concept distinguishes between “inside” (the torso, elbows, and knees) and “outside” (the extremities like hands, feet, and head). This distinction informs the Ten Word Formula: retracting the elbow without retracting the hand preserves the separation of inside and outside during inward movements. Conversely, retracting the hand without the elbow (顺/shùn, going along) balances inward energy with outward motion. Similarly, extending the hand without the elbow (逆/nì, counter) balances outward energy expansion, while extending the elbow without the hand enlarges the structure without disrupting the inside-outside relationship. Master Hong emphasized that the Ten Word Formula governs all Tai Chi movements, from forms to applications. Actions that appear as pulls are initiated by the elbow, while pushes are led by the hand, maintaining the integrity of the inside-outside dynamic. This rule also applies to specialized movements, such as punches, kicks, and elbow strikes. Through a meticulous analysis of Tai Chi mechanics, Master Hong provided a systematic framework for understanding and practicing Tai Chi. The Ten Word Formula resolves the Yin-Yang interplay within the body’s shifting structure, ensuring that “the inside stays inside, and the outside stays outside” (内不出,外不入). He encapsulated this wisdom in the phrase: “另一圈,八法含,基本功,莫輕看” (“Within its circle, all eight techniques are contained. This is basic training—do not take it lightly”). |

|

The eight techniques—Peng (掤), Lu (捋), Ji (挤), An (按), Cai (採), Lieh (挒), Zhou (肘), and Kao (靠)—are all rooted in this circular foundation. As Master Chen reminded practitioners: “出的时候,手领着。收的时候,肘领着。这是个动作的一个规则,和原则” (“When extending, the hand leads. When retracting, the elbow leads. This is both a rule and a principle of movement”).

5. Concave circle comes first – Action’s external shape (凹圈在先-动作外形)

| Tai Chi stances require precise shapes, both overall and in their individual parts. The overall stance should resemble an upright egg with the larger end at the bottom, or roughly a pyramid shape. The forward circle resembles a flat-lying egg with the larger end facing outward, while the reverse circle is similar, but with the smaller end facing outward. The front arm exhibits both convex and concave shapes, with training specifically focusing on the concave shape. Notably, this concave shape is a distinctive feature within the entire Tai Chi tradition.A key aspect of practical boxing is the emphasis on the concave circle. This shape takes priority. To understand the concept of the concave circle, imagine a simple circle. Master Hong often used a tire as a visual aid, explaining the shape using the tire’s structure. |  |

|

When viewed from the outside, the circle appears complete. However, when examining only half of it, one side appears convex, while the other, when turned over, shows a concave shape. In three dimensions, if you cut the circle horizontally, the front half is convex, and the back half is concave.

In our practical boxing, we shift our perspective to view the circle differently. While many practitioners focus on the outward convex shape, we focus on the inward, concave curve. This emphasizes the inner part of the circle, much like the inside of a bicycle tire. Master Hong frequently referred to the “inner tire” (concave) and “outer tire” (convex) to describe these contrasting surfaces, and this principle applies to all circular movements in Tai Chi. Every circle inherently contains both halves, regardless of the viewing angle. While not always explicitly emphasized by many teachers, the concave circle was frequently used by Master Hong’s teachers and earlier practitioners. Recognizing its significance, Master Hong devoted much of his teaching to explaining this concept and its underlying mechanism. He also connected it to the concept of ‘jing’ (force or energy) in Tai Chi. He described ‘bengzha jing’ (explosive force) as similar to hitting a spinning tire head-on, causing it to rebound with force. He also described another force, likening it to being pulled into a blender, where the force churns and pulls inward. |

The concave circle is particularly important in practical boxing, influencing the shape of our punches. Although the movements may look similar to those in other styles, the execution is different. In this style, we initiate with an inward, concave movement before extending outward to a fixed convex posture.

This method is distinct because, unlike many practitioners who initiate movements from the inside and move outward to create concave and convex shapes, our approach starts from the outside. We fix the convex shape and then move inward, creating the concave curve. This inward movement is a key and unique feature of our style.

Why is this so unique? When dealing with a single circle on the body, it typically faces outward. However, when considering two circles on the body, a new dynamic emerges. The front circle utilizes the second half of the arc, while the back circle uses the first half, creating an interlocking mechanism. This interplay forms the foundation for our movements.

The front circle constitutes the inner circle of one shape, while the back circle forms the front of another. The point of interlock between these two circles occurs at a single point, which is located in the lower body, specifically at the waist. In the upper body, it corresponds to the armpit. When these points align, they form a vertical line between the shoulder and hip, with the interlocking point residing within the front circle.

Starting from the hip and extending toward the back foot, a second circle is formed. In a static state, two circles exist simultaneously, interconnected by this specific point. This is the fundamental mechanism, which emphasizes the importance of the concave circle.

Conclusion

| Master Chen is disseminating the legacy of Master Hong’s Practical Method internationally. A brief overview of this system highlights five major characteristics. The principles of this system are precise and unwavering. As Wáng Zōngyuè noted: “Originally, we were supposed to follow the opponent’s moves, But most mistakenly seek the farther path, A deviation of one millimeter at the source, Will cause an error of a thousand miles at the destination. Learners must be aware. (本是 “捨已從人”,多誤 “舍近求遠”。所謂 “差之毫釐”,謬以千里。學者不可不詳辨焉。)”

Master Hong further reminds us: “Follow the rules strictly, Through osmosis, you will be enlightened. The heart and the hand will both be forgotten. At this time, you and the rules are one. (嚴守規矩,潛化默通;心手兩望,自合準繩。)” Master Chen has worked tirelessly to ensure his students understand the fundamental principles and rules governing this rich and complex system. He emphasizes both the cultural context and the scientific nature of the Practical Method for Eastern and Western audiences alike. |

|

The importance of principles and theory is also emphasized by the 17th-century samurai and philosopher, Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵 c. 1584 – 1645), in his Book of Five Rings (五輪書), where he states: “If you know the way broadly, you will see it in all things. (道を広く知れば、ものごとに出合事也。- 如果你廣泛地認識道路,你將會遇到許多事情。)”

Through his dedicated teaching and emphasis on both cultural context and scientific principles, Master Chen ensures the continued vitality and accessibility of Master Hong’s Practical Method for generations to come.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Where are videos and books for this style? Do the basics what makes the advanced as seen in most everythjng?

I’d really like reference to instructional material as well as reference to others instructionals that already did an excellent job so no reason to make additional videos!

Thank You,

Bert Clayton

https://practicalmethod.com/online-students-starting-guide/