|

Traditional martial arts, exemplified by figures like Master Chen and his teacher Master Hong, emphasize restraint, responsibility, and ethical conduct over raw power or showmanship. Violence is viewed as a last resort, and martial knowledge is entrusted only to students of proven character, reflecting the deep responsibility teachers bear. The teacher-student bond, rooted in Confucian ideals, safeguards against the misuse of power, while historical betrayals and modern temptations like ego, fame, and wealth serve as cautionary tales. Modern comparisons between traditional martial arts and competitive sports or MMA often overlook the deeper purpose of these arts: self-cultivation, moral integrity, and the wisdom to wield power responsibly. At its core, traditional martial arts are not about victory in combat but about understanding one’s capabilities, respecting their consequences, and choosing restraint over aggression.

This is an essay based on Master Chen’s Lecture in Berlin 2014-05-06 on “Ethics and Real Skill in Martial Art“. |

Traditional martial arts emphasize restraint and responsibility, rejecting vigilantism—the act of taking the law into one’s own hands. Even if you believe someone poses a danger, martial ethics dictate that you cannot intervene with violence arbitrarily. Your body is not a weapon to be used without consequence.

For example, Master Hong expelled three students who resorted to violence outside of sanctioned competitions. Even within competitions, true masters exercise extreme caution, especially against younger or less experienced opponents. A single well-placed strike can cause lifelong damage: a broken arm might lead to chronic pain and conditions like rheumatism, while a knee injury could result in permanent mobility issues.

Master Hong himself embodied this philosophy, adhering to a principle of non-harm throughout his life. Legend tells of his master, Chen Fa Ke, who, despite living in turbulent times, only killed a bandit as an absolute last resort. The act weighed so heavily on him that he renounced real combat for the rest of his life.

Martial arts are not performances or displays of power. Techniques learned are not meant for casual demonstration or misuse. Breaking someone’s arm, even in competition, carries profound consequences—physical, emotional, and moral.

One of Master Chen’s Taiji brothers gained fame in China for breaking over 100 arms. While this may sound impressive, each injury represents profound suffering for the individual, their family, and their future. True understanding of martial arts reveals this tally not as a boast but as a somber reminder of restraint’s importance.

Tai Chi Chuan, despite being a martial art, emphasizes ethics and self-discipline. In ancient systems, teachers observed students for extended periods, evaluating not just their skill but their character. Only those deemed highly ethical were entrusted with advanced knowledge. This wasn’t because Tai Chi lacked effectiveness—it was because martial knowledge carried real-world consequences in a time when physical prowess could mean survival or dominance.

|

The emphasis on ethics in martial transmission doesn’t mean unethical individuals can’t become skilled fighters. It reflects the teacher’s duty to protect society, themselves, and other students from misuse of knowledge. Just as a marksman with a firearm poses a potential threat, so too does a martial artist without moral discipline.In traditional martial arts, the teacher-student relationship mirrors the Confucian ideal of filial piety. Teachers are addressed as Sifu (“teacher-father”), and students as Tudi (“student-son”). This relationship safeguards against betrayal and misuse of martial arts knowledge. |

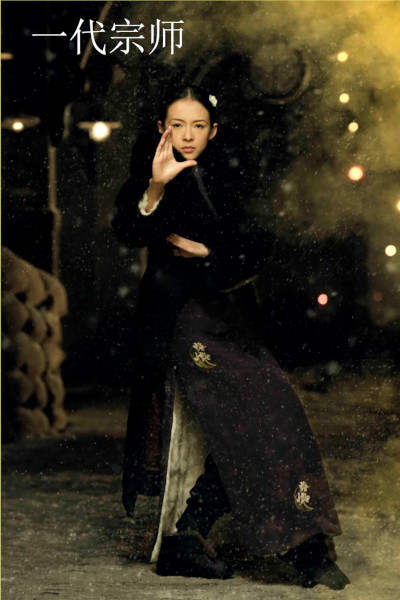

| Yet history is rife with stories of student betrayal. Wong Kar-wai’s film The Grandmaster (一代宗师) poignantly depicts this tragedy when a martial arts master is betrayed and murdered by his own student. Such stories remind us why many masters withheld crucial teachings until the end of their lives, fearing misuse.

As society evolved, Tai Chi Chuan’s martial applications faded in favor of self-cultivation. Yet the potential for misuse remains. True understanding of Tai Chi requires exploring its martial applications, but mastery brings risks. The initial thrill of learning destructive techniques can become intoxicating, fueling arrogance and a desire to dominate others. External temptations also pose risks. One of Master Chen’s talented students succumbed to arrogance after receiving community praise. This student’s initial dedication to the art disappeared after receiving financial gifts from various patrons. Such temptations are subtle and insidious, often taking hold before one realizes it. |

|

|

Master Hong considered himself fortunate to have avoided widespread fame. He believed political labels like “historical anti-revolutionary” shielded him from the corrupting influences of recognition. Fame, he observed, often changes a person’s character in ways only those who experience it firsthand can truly understand.

For Master Hong, true martial mastery transcends the desire to harm. Beginners test their skills eagerly, seeking validation. But with deep understanding, this need diminishes. A master knows the fragility of the human body and recognizes that even a light touch can cause irreparable harm. This profound respect for life is beautifully captured in Master Hong’s poem, “On Chen Style Taijiquan (洪式太極拳品並序),” where he writes: ‘Power without violence, Is the genuine power.’ (威而不猛,是謂雄渾。)” |

Tai Chi practitioners are encouraged to confront strong opponents, refining their technique through practice rather than aggression. This fosters an environment where challenges become opportunities for humility and growth, not mere dominance. The Practical Method emphasizes embracing these teaching moments. Notably, there is ample video evidence demonstrating students successfully navigating these challenges, showcasing their resilience and adaptability. For instances:

- 2013 Chen Xu Daqingshan Challenge

- 2014 Daqingshan Challenge (挑战 )

- 2015 Li Xiaohui Daqingshan Challenge (挑战李晓辉)

- 2015 Chen Xu Deals with Tough Visitor at Daqingshan

- 2020 Sun Yang on Taiji and MMA

However, challenges in martial arts differ from competitive sports. Traditional martial arts emphasize self-discovery, where success reflects internal growth. Sports, in contrast, prioritize external victory, where success brings public acclaim and failure invites ridicule. This distinction is often overlooked in modern comparisons between martial arts and sports.

Hypothetical comparisons—like a boxer’s jab against a jujitsu takedown—are inherently flawed. In real combat, every martial art offers tools, but no guarantees. True martial artists understand the moral weight of their skills, and their choices reflect that awareness.

As Master Chen paraphrased Master Hong’s critique of naively comparing martial arts skills, “If someone holds a gun to your head, would you attempt a counter-technique?” True martial skill transcends mere technical execution; it resides in the profound choice of when not to act. This choice stems from a deep understanding of ethics and a profound sense of responsibility.

|

Direct comparisons between Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) and traditional martial arts often fall short. While an MMA fighter may prevail in a competitive ring setting, this does not definitively establish superiority. Crucial factors such as rules, competitive context, and training methodologies differ significantly. Furthermore, success within traditional martial arts is not solely measured by competitive victories. Longevity of practice, development of character, and cultivation of self-awareness are equally, if not more, important. In fact, for practitioners of the Practical Method, any focus on countering an opponent’s specific actions can be detrimental to their own progress. |

At its core, traditional martial arts are not about domination or superiority but about balance—within oneself and with others. The greatest lesson they offer is not how to overpower an opponent, but how to wield strength with wisdom and restraint. This is the essence of true martial skill.